Niko Icardo is building an inertial electrostatic confinement fusor. It’s a device that uses an electric field to heat ions to conditions suitable for generating nuclear fusion reactions.

Icardo is not a nuclear physicist — not yet, anyway. He’s just a senior at Clark Fork High participating in the school’s new learning model where kids are exposed to real-world experiments. For Icardo, it’s applying his interests in quantum physics and welding.

“I wouldn’t get this opportunity in a normal class,” Icardo said. “I’m building a project that requires a lot of knowledge and I have to learn it on my own and apply it. It’s really cool.”

Clark Fork is trying for the first time this school year to align learning with students’ interests. Principal Phil Kemink and his eight teachers surveyed the 100 kids in grades 7-12. The staff found they were most interested in three areas — outdoors, arts and technology — so they created three learning “tracks” based on a combination of student interests, opportunities for community involvement, and teacher expertise and interest.

The kids are devoting 20 percent of school time to work in their chosen track.

“We’ve created a new paradigm for learning,” said Mike Turnlund, a social studies instructor at Clark Fork.

Clark Fork is one of Idaho’s most remote cities, nestled on the Montana border about 26 miles from Sandpoint (population 8,000).

Clark Fork’s main industry used to be logging but today, the 500 people who live in town largely commute or are retired. The school, part of the Lake Pend Oreille School District, also supports kids from nearby towns Hope (population 80) and East Hope (population 200).

“We are a unique place and I think that’s why we’re able to pull off this idea,” Icardo said.

The school has leveraged community resources for the new teaching model. Local businesses are partnering in the project by donating time, money and venues.

“Our community is participating at every level. We could not make it work without them,” Turnlund said. “It’s powerful — the people here are energized by this.”

In the “Great Outdoors Track,” students job shadow forest rangers, wildlife biologists and Schweitzer Mountain Resort employees. The kids learn about water stewardship, ecology, land use and conservation. Six acres were donated for the students to build a disc golf course while learning about soil, water and landscape architecture.

Earlier this month, nine forestry professionals from Kaniksu Land Trust volunteered a day to lead forestry-based instruction outdoors.

“The opportunities for learning and discovery are unlimited in an outdoor classroom such as this,” said Regan Plumb, a land protection specialist at Kaniksu. “ The gains to Kaniksu Land Trust are equally valuable: we’re helping to foster the next generation of conservationists, land stewards and natural resource professionals. “

In the “Art and Drama Track,” students are rubbing shoulders with professional artists and a Sandpoint bank is displaying their work. North Idaho College staff is helping the kids build a stage and drama production. One student is developing her own play.

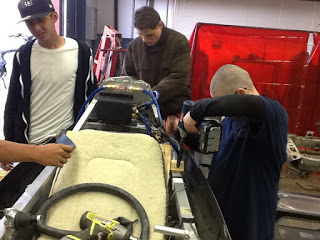

In the “Technology Track,” kids are assembling an electric racer. Another group is building a remotely piloted underwater drone. Icardo’s team is creating a Fansworth-Hirsch fuser.

“It’s crazy-wild watching these kids be so engaged in their learning,” Turnlund said.

School days are carefully coordinated in Clark Fork between time for tradition studies and devotion to the track projects, which are not only a time for career exploration but also presents a college readiness component. Every student completes a journal and regular essay reports on prompts such as these:

- Great Outdoors Track: “Why? Why are community service projects meaningful or useful? Why participate in them?”

- Art and Drama Track: “I will be able to create an understanding of an artistic process through demonstration, discussion, and written reflection.”

- Technology Track: “How will what you’re doing today have an impact on the rest of your life?”

“It’s not just a fun time — the activities are tied to learning and Common Core,” Turnlund said.

Teachers don’t assign tasks or homework in track learning. The process is flipped. Students decide their learning path and ask teachers for help or resources.

“These kids have been trained to be good students, to sit there and be quiet,” Turnlund said. “This teaches them the opposite, to be pro-active. They have to jump in and break away from the conditioning they’ve had. It’s something you just can’t teach.”

Icardo is interested in all sciences but says he wants to major in physics, possibly at the University of Washington, based on the experiences he’s had in the new track learning model. Apply welding and mathematics, things he’s interested in, has helped him decided on a career path.

“This gives me an opportunity to pursue and learn about something I wouldn’t get in class,” he said. “I really like it.”

For more about the program, check out the website designed for parents and community stakeholders.