Next fall, Victoria Hewitt will leave Sandpoint, a scenic small city tucked against North Idaho’s lakes and evergreen-lined mountains. She’s heading 500 miles south to Boise State University.

When she begins a journey to college that her parents didn’t make, she will already have credits in English, business and accounting. She will start as a sophomore, working towards a degree in information technology management.

When she begins a journey to college that her parents didn’t make, she will already have credits in English, business and accounting. She will start as a sophomore, working towards a degree in information technology management.

She says it has taken a lot of weekend work to juggle college classes with her high school curriculum. But the classes were free. Using Idaho’s advanced opportunities program, she will knock out her first year of college at taxpayer expense. “I’m super grateful that the state does that for us,” she said.

Hewitt is one of more than 32,000 students who took advantage of this growing program last school year. State officials hope the investment pays off — in a few years, when Hewitt enters the workforce, and in 15 to 20 years, when today’s elementary and junior high school students follow her.

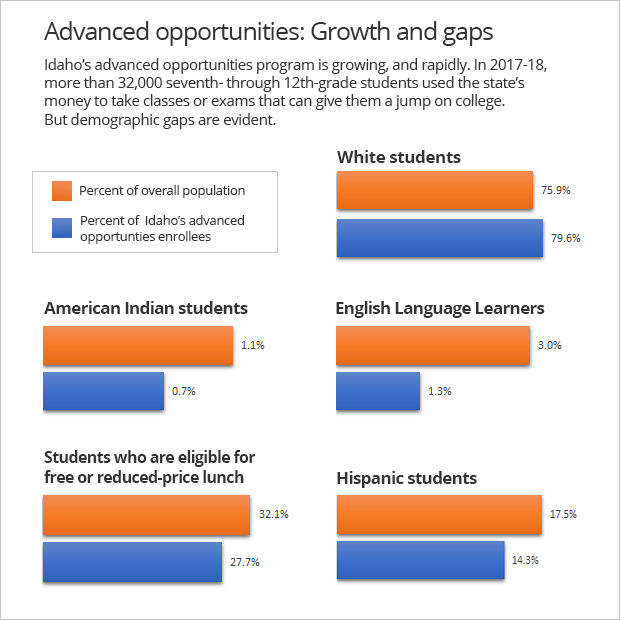

But the numbers show that this ambitious program only provides so much of a boost to students who need it most — rural students, students in poverty and Hispanic and Native American students.

Will the state’s big investment bridge Idaho’s demographic gaps?

Or reinforce them?

Idaho’s struggles, Idaho’s strategy

Like some 40 states around the country, Idaho has embraced an ambitious postsecondary goal. Come 2025, the state wants 60 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds to hold a college degree or professional certificate.

Most states are battling with their respective goals, but few have struggled as much as Idaho has. Since 2015, Idaho has been stuck at 42 percent.

No state is likely to reach its goals — and prepare young adults for the changing job market — by doing more of the same. Catering to students from well-educated families and high-performing schools won’t move the numbers or reinvent the workforce.

“These goals can only be met by better serving those students who have typically been underserved — first-generation, low-income, adult, and minority students who may need additional supports and services to succeed,” the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association wrote in a March report. “The cost to effectively serve these students may be higher, but state lawmakers have an obligation to support these students in order to meet attainment goals and workforce needs in a time of constrained resources.”

Since 2013-14, Idaho has spent at least $133.4 million to try to move closer to the 60 percent mark.

Let’s examine four line items.

College scholarships: $56.9 million

For students who get a share of the money, the Opportunity Scholarship provides up to $3,500 a year.

And according to a November 2017 State Board of Education report, the need-based scholarship is hitting the target demographics. Eligible students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch are more likely to apply than students who don’t receive lunch subsidies. Qualified Hispanic and Native American students are more likely to apply than white students.

Even in a state that prides itself on a low college sticker price, however, the Opportunity Scholarship only does so much.

“The Opportunity Scholarship just covers tuition and fees at the two-year institutions and covers about half of tuition and fees at the four-year institutions in Idaho,” the State Board said in its report. “Therefore, even students who receive the scholarship will still have to have other sources of funds in order to attend college.”

Legislators are putting more money into the scholarship, including $13.5 million this year, a new high-water mark. The number of students receiving a cut of the money tripled from 2014 to 2017.

Still, the scholarship is in high demand. In 2017, 3,716 students received scholarships; 5,245 eligible students applied for the money.

Lawmakers must put more money into scholarships, just to keep pace. The state’s top priority is to provide ongoing scholarships to returning students, and a high number of continuing awards can squeeze out eligible first-year students.

Adding to the pressure, the State Board can siphon up to 20 percent of scholarship money into new “adult completer” awards for older students. This scholarship is off to a slow start — with only $77,875 in awards for fall semester — but supporters see the program as a key to getting 25- to 34-year-old students back in school and working towards a degree. And that, in turn, will help underemployed Idahoans pick up new job skills, said State Board member Debbie Critchfield.

Advanced opportunities: $35.3 million (or more likely, $44.2 million)

Lucy Padilla knows about the power of the advanced opportunities program. The College of Southern Idaho’s early college coordinator has seen her daughter rack up dual credits, and she will leave high school with an associate’s degree.

So when Padilla spoke at a recent Hispanic youth summit at CSI, she tried to rally students to the idea. “It is hard. I’m not saying it’s easy,” she said. “(But) it is very doable.”

But when she asked for a show of hands, in a classroom of about 25 students, only a couple of students said they knew they too could earn an associate’s degree before graduating high school.

But when she asked for a show of hands, in a classroom of about 25 students, only a couple of students said they knew they too could earn an associate’s degree before graduating high school.

The episode is telling.

State leaders tout the advanced opportunities program as a groundbreaker and a life-changer. By providing every student $4,125 to take dual-credit courses or Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate tests, they hope to cut the cost of college for students such as Hewitt, the Sandpoint senior.

Students are responding. The state put $7 million into the program for 2017-18. Students signed up a startling $15.9 million in courses. Next year’s Legislature will have to cover last year’s unpaid bills.

Assuming that happens, as occurred in 2018, that will bring the bottom line to $44.2 million.

Still, success has been sporadic — and skewed:

- Idaho Education News analyzed advanced opportunities signups for 2017-18, looking at per-pupil spending. Four rural districts — Troy, Cottonwood, Melba and New Plymouth — landed in the top 10. Charter schools accounted for the rest. As in 2016-17, students in urban districts and charter schools were again more likely to use the program.

- Across the state, rural administrators say they struggle to find qualified teachers for advanced opportunities courses.

- By the State Department of Education’s own account, students from several key demographic groups are less likely to sign up for advanced opportunities. Included on this list: Hispanics, Native Americans and students who qualify for free or reduced-price lunch.

And while Padilla encouraged students to tap into the state’s money, the University of Idaho’s Monzerrath Stark sounded a cautious note. Some rural students, struggling with high school math, may be afraid to take on a college-level class.

“The students are, at times, their own worst critics,” said Stark, the U of I’s associate director for multicultural admissions. “And they pull themselves back.”

College and career advisers: $21 million

As Hewitt prepares for college, she credits counselor Jeralyn Mire with helping her and her parents through the application maze. “It’s all been very new to me.”

None of this is new to Mire, Sandpoint’s postsecondary transition counselor. When she talks about walking students through a process that can be “paralyzing,” she exudes experience and enthusiasm. “(I’m) this annoying fly continually buzzing around (students), especially their senior year.”

Mire was an assistant dean of admissions at nearby Gonzaga University before coming to Sandpoint. She joined a district that had already ramped up its counseling efforts, using a grant from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.

In 2017, 57 percent of Sandpoint’s graduates went straight to college, well above the state rate of 45 percent. Mire credits the district’s persistence. “It takes a while to get some systems going … and change the culture.”

Other districts are playing catchup, through the state’s college and career advisers budget. Three years in, this line item has grown steadily, reaching $9 million for this year.

In theory — and indeed, in many schools — the money bankrolls positions such as Mire’s. But the money goes out based on enrollment; for 2017-18, the median payment to districts and charters came to only $14,000. As a result, small districts frequently put some or all of their limited money into student trips to campuses or college fairs — and not staffing.

Other districts hire near-peer mentors, recent college graduates just entering the work force. The State Board says the mentoring programs appear to improve go-on rates, but Mire says too many schools are simply throwing newcomers into the fray. “They really don’t know what they’re doing.”

Student achievement tests: $11.7 million

Idaho high school students are required to take a college-placement exam — whether they plan to go to college or not. Since 2012, the state has paid about $1 million a year for juniors to take the SAT during the regular school day.

The state also covers costs for the PSAT, a precursor test geared toward sophomores.

The logic behind SAT Day is simple: When students take the test, they are more likely to apply to college. That has been borne out in research in Michigan and Maine, two other states with SAT Day, said Jeff Carlson, a Council native who is now a senior director with the College Board, the nonprofit that administers the PSAT and SAT to about 7 million students annually.

But research also shows that practice pays off. On average, students score 60 points higher the second time they take the test — a significant uptick, even though the SAT grades on a 1,600-point scale. For students who study before the retest, Carlson said, the increase is even greater.

But Idaho’s SAT Day is a one-shot proposition. If students want a re-do, they must pay for it.

And Idaho’s SAT scores still reveal wide demographic gaps. Hispanic and Native American students scored well below the state’s average. So did potential “first-generation” college students.

Alternatives to college

College scholarships. Dual-credit college courses. College placement exams. College and career counselors.

There is a recurring theme here.

Some educators think the 60 percent goal sends a mixed message, or emphasizes college to the exclusion of other options.

And as a result, they are pushing alternatives to college — and options to help high school graduates go straight into the workplace.

Disclosure: Idaho Education News is funded by a grant from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.

This story was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.

This series, at a glance

- In order to reach its “60 percent goal,” Idaho will need to reinvent itself. And rethink success.

- In Weiser, graduates look at going on — and, probably, moving out.

- Idaho has spent $133 million, and counting, to help high school graduates continue their education. Will all this money bridge Idaho’s demographic gaps? Or reinforce them?

- For Hispanic students — Idaho’s largest minority — college access often hinges on college affordability.

- In rural communities, career-technical education emerges a pathway to the workplace — and a way to make college more affordable.

- In Mini-Cassia, a competitive labor market creates a unique learning opportunity for students.

- The 60 percent goal defines a target, while trivializing the challenge. In many households, education beyond high school is seen as unaffordable and unnecessary.

- Native American students lag behind their classmates on many education metrics — but there are glimmers of hope.