More than 98 percent of Idaho teachers earned one of the top two overall scores on their evaluations during the 2018-19 school year.

According to new data released by the State Department of Education, 18,485 of Idaho’s 18,834 teachers earned overall scores of “proficient” or “distinguished” on their annual evaluations.

Percent of teachers earning scores of proficient and above:

98.1 (2019)

96.4 (2018)

97.2 (2017)

96.3 (2016)

97.8 (2015)

That’s the highest percentage of teachers earning top marks since Idaho Education News began tracking evaluation data in 2015. Idaho teachers can earn one of four evaluation scores: “distinguished,” “proficient,” “basic” or “unsatisfactory.” However, some districts — including Boise, the state’s second-largest district — don’t use the distinguished rating and only award three possible scores. In Boise, 99.4 percent of its 1,768 teachers earned scores of “proficient.”

Teacher evaluations are important — and increasingly controversial — because the Legislature partially tied a teacher’s ability to earn more money to performance on evaluations.

But evaluations are more than a means to earn higher pay. Charlotte Danielson’s Framework for Teaching, the basis for Idaho teacher evaluations, was developed as a tool to help teachers grow and improve their craft; and to provide a universal tool to define good teaching.

By state law, school administrators must factor student achievement into teacher evaluation scores. While 98.1 percent of Idaho teachers are proficient or above, just 44.4 percent of Idaho students were proficient in math. Only 55 percent of students were proficient or above in English language arts, according to SDE data.

Although the highest percentage of teachers statewide earned top marks last year, there are signs administrators are starting to differentiate between their teachers. In 2014-15, for example, 35 districts or charters reported that every single teacher earned an identical overall evaluation score. For 2018-19, that number dropped to 19 districts or charters.

Snapshots how districts approach evaluations

Lakeland Superintendent Becky Meyer said her district takes evaluations and oversight of its teaching staff extremely seriously. During an education task force subcommittee meeting last month, Meyer criticized the Legislature, the media and Idaho Education News specifically for “misrepresenting” teacher evaluation data. Meyer said administrators work with teachers who aren’t yet proficient to develop a continuous improvement plan. And if they don’t improve, Meyer said the district doesn’t want them around.

“If we have a teacher that is basic, that means they are on a formal improvement plan, and they definitely get an opportunity to improve,” Meyer said. “If they don’t improve next year, then we take steps to not have them teach any longer because they can’t improve. We want them to be as great as possible for kids.”

In Lakeland, the evaluations process plays out during the entire school year. At the beginning, each teacher completes a self-reflection where they evaluate where they think they are at within 22 components of the Danielson Framework.

They identify areas of strength, and areas where they would like to grow. Then they develop SMART goals (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and timely) to reach those goals and work with administrators to get there.

Administrators, such as a principal, visit each classroom weekly for an informal walkthrough, and then at least two more formal, documented observations are factored into each evaluation.

Along the way, administrators record videos of educators teaching and provide mentoring and professional development, Meyer said.

“The feedback we give them is continuous,” she said.

In Lakeland, 98.6 percent (284 of 288) of teachers earned the same score of proficient (Lakeland doesn’t award scores of distinguished). The other four teachers were rated basic. Meanwhile, just 37.5 percent of Lakeland High’s students are proficient in math. Meyer said teachers set their own student achievement goals, which may be tied to growth, not overall proficiency.

Several of Lakeland’s proficient teachers earned scores of basic on individual components of the evaluation, but still did well enough to earn overall scores of proficient. Meyer said teachers should be able to rack up enough high scores in certain areas of the evaluation, (professionalism, organizing their physical space and communicating with students and families) that even if they struggle with other aspects of the evaluation (designing instruction, using assessment in instruction or managing student behavior) they should have enough high scores to earn an overall proficient score.

Meyer insisted that would still be the case even for a new teacher, who hasn’t had the benefit of a long mentorship and professional development, or a teacher who entered the classroom on an alternative certification and did not complete an educator preparation program at a college or university.

“I’m not saying it’s easy, but you can learn that,” she said.

In other districts, the changing education landscape introduces new dimensions to evaluations. Along the Utah border, the once-tiny Oneida School District has grown enrollment and teachers by leaps and bounds by contracting with digital curriculum providers. Enrollment shot up by 37 percent in two years, Idaho EdNews previously reported. Many of those students take all of their courses online, and never set foot in a brick-and-mortar classroom.

Now, about 70 of Oneida’s 129 teachers teach only virtually — often using a web camera and computer from their home, Superintendent Rich Moore said.

Because those teachers never enter a school, that means Terri Sorensen, principal of Oneida’s Idaho Home Learning Academy, must log in virtually — just like her students — to handle the observations and walkthroughs that make up Oneida’s teacher evaluations. The overall process is similar to evaluating at a brick-and-mortar school, but they use an updated version of Danielson’s Framework that is designed specifically for online learning environments. Because Oneida’s explosive growth has played out over the past three years, district officials have reached out to online schools in places like Florida to learn how established virtual schools handle evaluations.

“In terms of delivering education services and support (virtually) the rest of the country is maybe a little further down the road than we are as a district, and we’re trying to learn as much as we can from those who forged a path before us.”

Because of that support and Danielson’s updated rubric, Sorensen said, “We aren’t reinventing the wheel here.”

Changes coming?

This summer, Gov. Brad Little’s Our Kids, Idaho’s Future K-12 task force has debated teacher evaluations and master educator premiums. Some task force members, particularly some business leaders, have raised questions about evaluations.

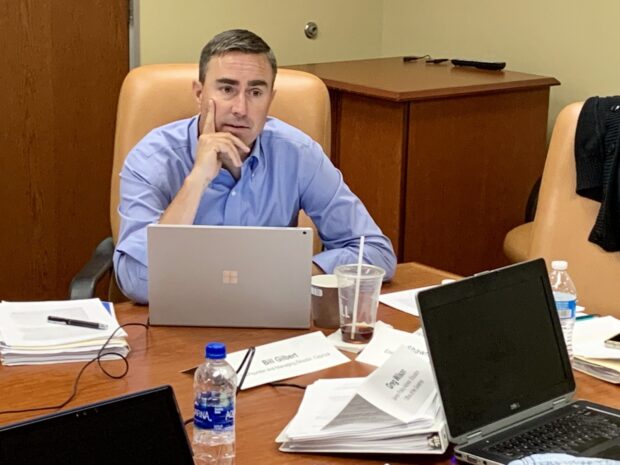

“Successful evaluations should not all look the same; I think we can all logically understand that,” task force co-chairman Bill Gilbert said. “Even in a successful enterprise or school building you can have a culture of success and student growth and perform well, but it is unlikely all of your employees or teachers are all going to be at exactly the same level.”

Charlotte Danielson, the creator of the Danielson Framework, made the same point in an interview with Idaho Education News two years ago.

She said the public should consider it a red flag if a district, school or state reports that all or nearly all of its teachers earned the same top scores.

“People are justified in being skeptical of how accurate evaluations are because in most states 98 percent of teachers are given the top two ratings, or some unlikely percentage — nobody really believes that’s the case,” Danielson said.

Gilbert was careful not to get out ahead of the task force, which doesn’t have to deliver its recommendations to Little until this fall. But he suggested one potential issue with evaluations is administrators’ workload.

“In some cases, though not all, a principal has 30 evaluations they have to complete,” Gilbert said. “How do you create enough time to complete thorough evaluations, so it doesn’t become a purely administrative exercise? In most corporate business environments, you don’t have that many direct reports.”

Gilbert wants to let the task force finish its work organically without pushing early for specific recommendations. But he has debated the idea of whether self-evaluations should be more a part of the mix, or whether student or parent input should be weighed. Overall, he has stressed that the task force is interested in both accountability and helping schools recruit, retain and mentor excellent teaching staffs.

Where Idaho stands

Elizabeth Ross, managing director for teacher policy at the National Council for Teacher Quality, said Idaho uses best practices by offering four scores that educators can earn on their evaluations. That’s preferable to states that only offer two scores — satisfactory or unsatisfactory — and make it nearly impossible to differentiate quality and performance among teachers.

Ross also said Idaho has adopted “more rigorous” evaluations that must include student achievement (although Idaho’s law no longer specifies what weight student achievement is given) in evaluations.

Idaho is also in the minority of states that tie pay to evaluations. Ross said Idaho is one of 19 states that either require or allow performance benchmarks to be tied to teacher pay. Elsewhere, 32 states are silent on whether to include performance as a measure for determining teacher pay, she said.

Ross said there isn’t an industry standard for the level of differentiation to expect between evaluation scores. But she said she would expect more differentiation, as Idaho gains more experience with evaluations under the parameters set out in the five-year-old career ladder law.

“What you see in Idaho, as well as many states across the country, is the full promise of a more objective teacher evaluation system that has not yet been realized,” Ross said.

History of flawed data

Since the Legislature’s 2015 action to tie pay to performance on evaluations, Idaho Education News has documented several flaws and problems with evaluation data.

- In 2015, Rep. Ryan Kerby, then-superintendent of the New Plymouth School District, told Idaho EdNews that his district intentionally awarded identical scores to all of its teachers because “We feel the state should be concerned with whether kids are learning, not if Mrs. Smith got proficient or unsatisfactory or basic.”

- In 2015, Alan Dunn, then superintendent of the Sugar-Salem School District, told Idaho EdNews he altered teacher evaluation data intentionally in what he described as an attempt to protect employee privacy. Dunn reported to the state that all Sugar-Salem teachers received identical overall evaluation scores, even though that was not the case.

- In 2016, Post Falls Superintendent Jerry Keane told Idaho EdNews his district inaccurately reported all 301 teachers received identical overall evaluation scores in order to meet a state reporting deadline. Keane then supplied updated, accurate evaluations data.

- In 2017 the Professional Standards Commission, which oversees teacher certification in Idaho, reprimanded both Kerby and Dunn for violating state law and ethics rules when they submitted inaccurate teacher evaluation data to the state.

- In 2018, the State Board of Education reviewed a sample of nearly 800 teacher evaluations and found that 56 percent of the evaluations for 2016-17 complied fully with state evaluation laws.

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed research to this report.

2018-19 teacher evaluations by the numbers

- Distinguished: 3,109 teachers, 16 percent

- Proficient: 15466 teachers, 82.1 percent

- Basic: 325 teachers, 1.7 percent

- Unsatisfactory: 24 teachers, 0.1 percent.

Percent of Idaho students scoring proficient and above on the ISAT:

- Math: 44.4 percent

- English language arts: 55 percent

Districts and charters that awarded ever single teacher an identical overall evaluation score of “proficient”:

- Lewiston, 310 teachers.

- Freemont County, 133 teachers.

- Cottonwood, 31 teachers.

- Victory Charter, 28 teachers.

- Liberty Charter, 26 teachers.

- North Idaho Stem Charter, 25 teachers.

- Canyon-Owyhee School Service Agency (COSSA), 21 teachers.

- Meridian Technical Charter, 16 teachers.

- Salmon River, 16 teachers.

- Culdesac, 15 teachers.

- Mullan, 15 teachers.

- Idaho STEM Academy, 15 teachers.

- Idaho Distance Education Academy, 15 teachers.

- Peace Valley Charter, 15 teachers.

- Legacy Public Charter, 14 teachers.

- Kootenai Tech Ed Campus (KTEC), 11 teachers.

- Payette River Technical Academy, 11 teachers.

- Chief Tahghee, nine teachers.

- Kootenai Bridge Academy, six teachers.