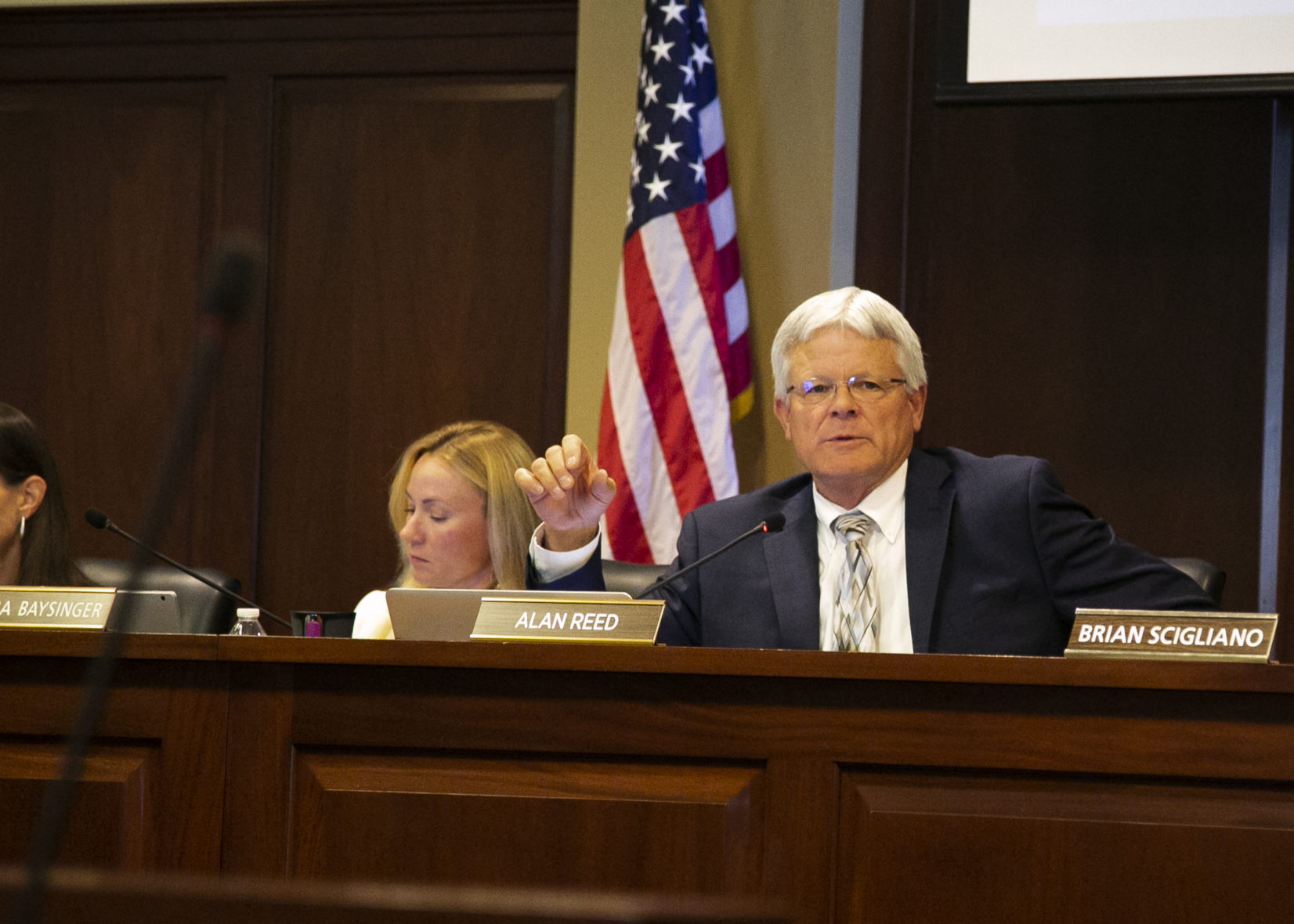

By day, Alan Reed owns a family dairy — well-known around Idaho Falls for its ice cream products.

But Reed has spent the summer mired in political controversy, even though he says he wants what his critics want. “Choice is important, alternatives are important, when it comes to education.”

Reed chairs the Idaho Public Charter School Commission. Critics say commissioners are beholden to an unprofessional, biased staff. They say the commission’s rhetoric and Reed’s recent apologies to charter leaders belie a desire to shutter schools.

As Idaho’s charter school sector grows, reaching an enrollment of 25,000 students, the commission has become a polarizing force. Some charter leaders still defend the commission, despite recent missteps. Reed has been trying to mend fences with political leaders, and it appears the commission still has powerful Statehouse allies.

How we got here

The controversy dates back to April 11, when commissioners and staff met for nearly two hours behind closed doors.

The stated reason for the executive session was legal; commissioners wanted to review confidential student data. The discussion drifted. Commissioners talked about the politics of closing charter schools — and what it would take to bring legislators around to the idea. They made disparaging remarks about Heritage Academy, its administrator and the community it serves. At one point, Reed expressed regret that the Jerome school remains open. (Reed later apologized, and tried to meet with Heritage officials, who rebuffed the invite.)

Responding to a series of complaints, Attorney General Lawrence Wasden’s office launched an investigation, and concluded that the commission probably violated Idaho’s open meeting law. The commission met one week later, admitted to breaking the law and received training from a Wasden deputy.

“There is an issue, and rightly so, of trust,” Reed said in a recent interview. “(You have to) behave yourself out of it.”

For critics, the problem transcends one illegal meeting. The commission has shown clear animosity towards some charter schools, and those schools’ leaders don’t want to respond to an adversarial agency, said Tom LeClaire, president of the Coalition of Idaho Charter School Families.

“It’s become a dead relationship, and that’s not what we want,” he said.

The contentious relationship has a lot to do with the commission’s role.

Who are these guys — and what do they do?

Supported by four staffers, the commission’s seven volunteer members wield considerable power over charter schools.

The commission serves as authorizer for three-fourths of Idaho’s charter schools. Last year, more than 16,000 students attended charter schools under the commission’s bailiwick. That number will grow this fall, as four new commission-approved schools open their doors.

The 46-school portfolio includes large Treasure Valley charters, such as Sage International School in Boise and North Star Charter in Eagle, and smaller schools serving McCall, Gooding and the Fort Hall Indian Reservation. The commission oversees schools that post some of the state’s top test scores, and virtual schools serving a high proportion of at-risk students.

The Legislature created the commission in 2004, in order to give charter advocates another way to open a school. Colleges and universities can authorize a charter, but none ever has, and some school districts are uninterested in authorizing charters.

Reed is glad the commission provides a path to opening a new school. But at the same time, the commission faces a constant balancing act — between approving schools and providing oversight, and fostering innovation and protecting public money.

“We do not want the taxpayer throwing money at an idea that we’re pretty confident is going to fail,” he said.

But LeClaire says the commission has done a “terrible” job as an authorizer, forcing applicants to navigate a time-consuming paperwork process. He concedes that the commission has an oversight role, but says the group has abandoned its support role and talks, at least privately, about closing schools.

“This isn’t a regulatory agency,” he said.

Some charter officials may chafe at the scrutiny, but the commission cannot simply walk away from schools it authorizes. Defenders say the commission must hold schools accountable for student performance and financial management.

“That is their job,” said Terry Ryan, CEO of Bluum, a Boise nonprofit supporting school choice, and a board member of the Idaho Charter School Network. “That’s what they’re supposed to do.”

Two national reports, two schools of thought

Depending on who you believe, the commission is a roadblock or a rubber stamp.

The Center for Education Reform, a Washington, D.C., school choice think tank, gives Idaho’s charter school law a “C.” The commission is part of the problem, according to the 2018 report.

“State government and the quasi-independent Idaho Charter School Commission heavily regulate the charter sector,” the center wrote. “This has stalled the growth of Idaho’s charter sector.”

Making matters worse, according to the center, is that the commission is the only game in town — approving charters when universities won’t and many school districts don’t.

A National Association of Charter School Administrators report paints a different picture.

The commission approved all eight charter applications it received in 2017 and 2018; the national average is 35 percent. During that same time, the commission approved all 25 schools that came up for renewal, including 14 that had received an academic designation of “remediation” or worse. In 2018, the commission recommended renewing four schools, even though they “were not meeting financial performance expectations.”

The national association floats several possible explanations. “Commissioners noted that strong pro-charter groups have created political pressure to renew charter schools across the state,” according to the report, presented to the commission in April.

The group dismisses Idaho’s commission as something of a regulatory “wimp,” Reed said, and he isn’t persuaded.

“They’re not from Idaho, that’s how I take it,” Reed says of the Chicago-based reviewers.

The commission’s detractors

In June, the commission inadvertently released audio from the April 11 meeting. When LeClaire listened to the recording, it confirmed many of his suspicions about how the commission views schools under its jurisdiction. “The lights went on,” he said this week.

Since then, his group has emerged as the commission’s most relentless opponent. When the state released 2018-19 Idaho Reading Indicator scores this month, and Heritage Academy posted some of the state’s biggest improvements, the coalition again accused the commission of using sloppy research to impugn schools. In an online petition drive, the coalition is demanding an independent investigation of the commission.

The criticism circles back to recurring themes. Commission staff places onerous paperwork restrictions on charters. The commission plays favorites, scrutinizing schools it considers low-performing. And even though the commission has closed only two charters in 15 years, the closed meeting reveals a darker agenda.

LeClaire says the coalition has “several thousand” members statewide — generally parents of charter students. (One of LeClaire’s three children graduated from Idaho Virtual Academy, the state’s largest charter school.) The group has no member schools, and parental members tend to come and go as their children enter or leave the charter sector.

Some schools are more willing to criticize the commission than others. Heritage Academy administrator Christine Ivie declined comment for this story — acting, she said, on the advice of counsel. In an email to Idaho Education News, Idaho Virtual Academy Head of School Kelly Edginton spoke of a “challenging” relationship with staff.

Edginton bristled at the suggestion that her online school wants to skirt accountability. She said she wants fair accountability. And she says the commission labels schools like hers as poor performers, without recognizing that these schools serve high numbers of at-risk students.

“I believe members of the commission and their staff do not understand our school,” she wrote. “I don’t believe all of the commissioners want to close our school, but I do believe commission staff do want to close our school.”

The commission’s defenders

When the commission took public comments at an Aug. 1 meeting, it was almost as if speakers were talking about two different entities. LeClaire, Edginton and other critics said they could no longer trust a commission that did nothing to hide its contempt for some schools. Other charter advocates credited the commission with asking tough questions and providing the guidance they needed to get their schools on track.

Commission Director Tamara Baysinger attributes the split to a difference in philosophy. To some advocates, the charter movement is all about parental choice. To others, it is about building high-quality schools outside the traditional education system. “Not everyone in the charter community agrees what is most important.”

Some of the commission’s defenders run the highest-performing charters in Idaho: schools such as North Star and Meridian’s Compass Public Charter School. They’re also well-established schools, among the first charters opened in Idaho. “Not everybody’s in the same place where they are,” LeClaire said.

Ryan is among the commission’s defenders, and partly it’s a matter of practicality. Idaho is adding more than 2,000 charter school seats this year, almost all of them at commission schools.

“We do need the Idaho Public Charter School Commission if you want to have charter schools in this state,” he said.

Ryan knows opinions about the commission are split. Some charter advocates defend the group to the hilt, he said, while others want “to blow the whole thing up.” In the middle are charter leaders who want someone held accountable for the closed meeting fiasco.

Ryan lands in the middle, although he’s not sure who should pay the price. For Ryan, the audio from the April 11 meeting was a tough listen — and the talk about closing schools provided the commission’s adversaries a lot of ammunition.

“They sounded detached,” Ryan said of the commissioners. “They sounded remote. They didn’t sound empathetic.”

What the critics want

The commission was designed to provide another means to start a charter, but Edginton says charters now need an alternative to the alternative. “It’s clear there are numerous schools that deserve better from Idaho’s education establishment,” she said. “This may mean an alternate authorizer consisting of staff who have the credentials and experience to better understand our schools and has an interest in serving all students.”

LeClaire wants Gov. Brad Little to clean house. “I think it would be helpful to this commission if we got new blood as soon as possible,” he said.

But like Edginton, LeClaire says his larger concern is with commission staff, which he says holds inordinate sway on the appointed commissioners. He says he’d like to work on legislation to rein in the staff’s role. He knows that would be a tough sell with legislators who are loathe to micromanage state agencies.

But critics might face a more basic obstacle. The commission — appointed by Little, Senate President Pro Tem Brent Hill and House Speaker Scott Bedke — has a built-in political power base. And none of the three seem eager for an overhaul.

Little supports the commission, and sees it as a mechanism to hold charter schools accountable and keep schools compliant with state law, spokeswoman Marissa Morrison Hyer said Wednesday. “The commission generally does a good job performing a complex role.”

Hill says he’s willing to look at the issues as commissioners come up for Senate confirmation; three of the seven spots are up for renewal in 2020. “At this point, I’m not interested in making a wholesale change,” he said. “They’re laypeople, just trying to do the best they can.”

Bedke is baffled by the claims that the commission is anti-charter. One of his apppointees, former House Education Committee Julie VanOrden, was a solid advocate for school choice during her days in the Legislature. And he suggested the controversy might be more of a short-term backlash coming from some members of the charter community.

“It would be nice if some other sponsoring entity would step up and get through this rough patch,” he said. “The phone’s not ringing.”

Disclaimer: Bluum and Idaho Education News are funded through grants from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.