The week after his daycare closed, Erin Erkins’ toddler, Ander, would grab his shoes, find his lunchbox and wait expectantly at the front door.

“He wanted to go to the car and go to school,” Erkins said.

Even at 18-months old, Ander thrives on routine.

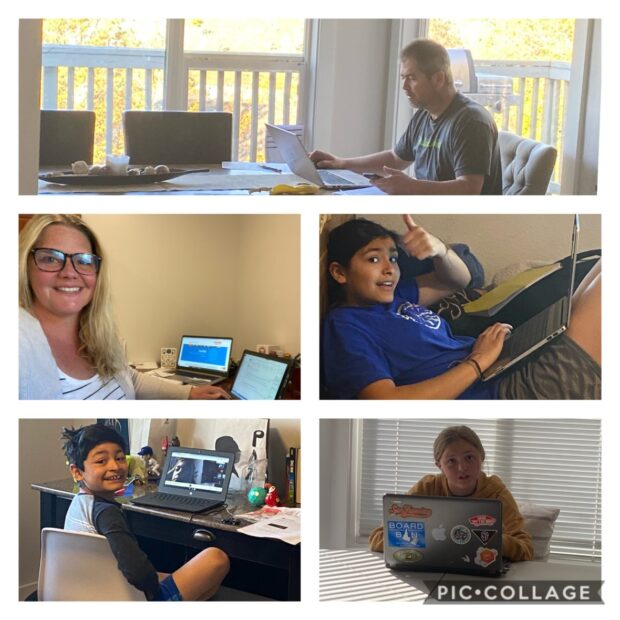

Idaho families are nearly two months into an unprecedented distance-learning experiment. Parents, thrust into the role of homeschool teachers and aides, are balancing jobs with schoolwork, and tripping over their children and spouses at home.

Without the familiar structure of work, school and clubs, some Treasure Valley parents say that recreating a routine has been their saving grace.

“I like to have everything planned out — it helps them, and it also helps me, somewhat, stay sane,” Erkins said.

The Erkins

Erin Erkins manages two elementary school kids, a toddler, a 3-month old and her job doing marketing for family company Erkins Commercial Real Estate.

Her oldest daughters — a fourth grader and a kindergartner — are up at 7:30 for gymnastics practice. During the height of closures, Erkin said, the girls practiced on Zoom. Recently, they’ve headed back to the gym.

Then comes breakfast and reading and schoolwork until early afternoon with breaks for lunch and a family walk. Erkins’ kindergartner needs hands-on help with reading and sight-word practice, so she plans for that during Ander’s mid-morning and post-walk naps.

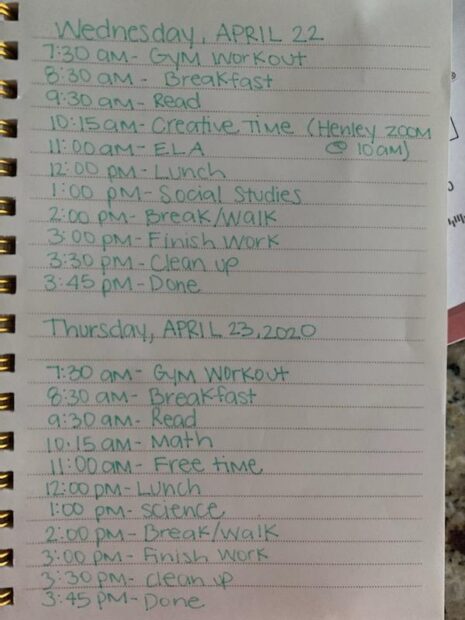

Erkins’ daughters are in the Boise School District, which shut down in mid-March, then rolled out educational materials over the following month. For the first few weeks of closures, Erkin didn’t set a schedule for her kids. When she started writing things down, Erin noticed her daughters would wake up every morning excited to see the plan. Her husband would look at it to see how the family schedule lined up with his day.

“There are some days that you’re just totally off schedule, and I just had to learn to accept that,” Erkins said. “I can be pretty type-A, I want the house clean, but during all this — it’s chaos, and you have to be okay with that.”

Sarah Cortez:

9 a.m. -11 a.m.: School work

11 a.m.-1 p.m. lunch break and fun

1:00 p.m.: Walk the dog/physical activity

2:00 p.m: Read

2:30-3:00 p.m. — end of school day.

Extras: Projects like Albertsons monopoly, applying for jobs, chores.

It takes Sarah Cortez’ elementary school kids about an hour and a half to finish their schoolwork.

In fourth and sixth grades, the kids get on Zoom calls with their teachers in the morning, and spend a few hours working on the assignments prescribed by the Boise School District. Even with lunchtime, reading and an hour of dog-walking mixed into the Cortez’ daily schedule, the school day is typically over by 2:30 or 3 p.m.

“There’s definitely not a full day of school work for each kid,” Cortez said. “That’s fine, but it makes it a little heavier for us to figure out a schedule for the day.”

Chores and extra projects — like setting up an Albertson’s monopoly board — help keep the younger kids busy while Cortez and her husband work from home. Their oldest daughter, a sophomore, is a self-starter and manages her schoolwork at her own pace with the occasional parental assignment— like applying for summer jobs — thrown in the mix.

Cortez, who works for Alliance Title and Escrow, never wanted to be a homeschool teacher. On a 5-star scale, she rates herself at a 3. She worries about whether the kids will be on-track next school year, in part because she’s not trained to teach them. She struggles to help with math, in particular, because her kids are learning long-division and multiplication using strategies she didn’t learn in school.

“I’m not educated myself on what they’re needing to know,” Cortez said. “I find Google is my best friend and I’m learning alongside of them.”

Troy DeRosier:

9 am – 12 or 1 p.m.: schoolwork

Broken up into 45 minute blocks for core subjects

During the day: have to read for 30 minutes from a book

Troy DeRosier warned his kids from the outset: In the first few days of distance learning “there are going to be some bumps and bruises.”

And there were. The very first day, DeRosier made his kids, in sixth and eighth grade, do twice as much work as they needed to because he misread the instructions. After weeks of downtime between school closures in the West Ada district and the rollout of online learning, getting back into a routine felt like coming back from summer break — with the added challenge of motivating the students, who know their performance on the distance-learning assignments won’t actually count against them.

Then there were the emails. He was — and sometimes still is — overwhelmed with up to 10 emails a day from the school district, the student’s middle school, and each of his children’s individual teachers.

“It was rocky to start with, and the school district was still learning its stuff,” De Rosier said. “Now that the system is in place, it’s been pretty smooth sailing.”

When they’re at his house, DeRosier’s kids start their at home learning around 9 a.m., usually working on classes and projects in 45-minute blocks. That typically lasts into the early afternoon, when DeRosier works on video production and teaching online classes for his company Dirt Road Dancing. Every other week the students are with their mom, and DeRosier said the parents have worked to keep a consistent schedule between the two households to keep the kids on track.

“They’ve enjoyed the schedule, because that’s what they’re used to with school. Keeping that — and not letting them convince me different — was helpful,” he said. “They can’t negotiate with their teacher, they can’t negotiate with their school on the times, they can’t negotiate with me.”