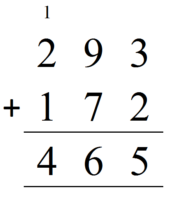

Amberlee Honsaker remembers learning only one way to add or subtract in elementary school.

It was the standard algorithm: stack numbers vertically, add the digits in columns, and carry the ones where necessary.

For her daughter, Raegan, math instruction extends far beyond that.

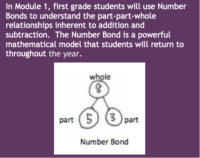

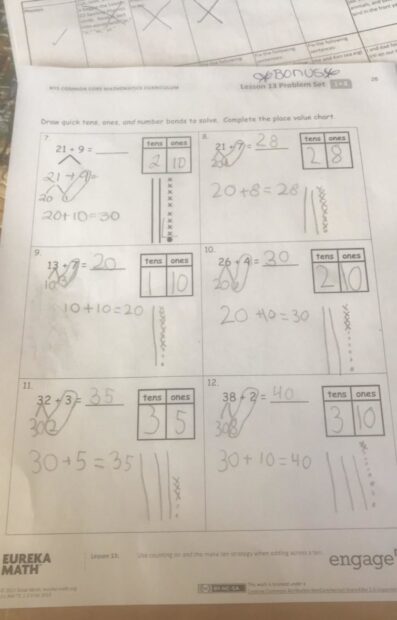

In first grade, Raegan is using number bonds, making place-value charts, drawing out 10s and ones — illustrating multiple methods for solving simple addition problems.

If you don’t know what those are, you’re not alone.

They’re methods that Honsaker never learned in school, either. And now that COVID-19 has pushed her from the homework helper into the role of go-to-teacher, Honsaker is learning the math methods alongside her 7-year-old.

“You’re looking at this paper, you’re looking at this poor kid, they’re waiting for instruction and it’s like, ‘I have no idea how to do this,'” Honsaker said. “So, you know, I Googled it.”

Elementary-aged parents say learning the way their students do math can be an added challenge to the distance-learning forced by coronavirus closures. Some, like Honsaker, are leaning into the unfamiliar methods to make sure students are on the same page as teachers and classmates. Other parents decry the oft-politicized “Common Core” math on social media, or have told educators they’re ditching the school’s methods to teach kids math their way.

Jen Crook, a second-grade teacher in the West Ada district, has parents who fall in both camps.

“It’s a challenge. At least, at the second-grade level, we’re laying a foundation for strong, solid number sense,” Crook said. “I don’t want to discount what parents are trying to do, but they’re kind of unraveling what we’ve taught.”

Where did these changes come from?

Over the past 40 years, education research has emphasized that teaching math should start with building students’ understanding of math concepts, instead of starting with formal algorithms, according to Michele Carney, an associate professor of mathematics education at Boise State University.

That conceptual understanding is a core part of Idaho’s math standards for young students. Idaho’s standards — which dictate what skills students should learn in each grade — are an adaptation of the Common Core standards adopted by more than 40 states 10 years ago.

The state’s standards do require that students can use the standard algorithm that Honsaker learned in elementary school by grades three and four. The earlier grades focus on building students’ understanding of concepts such as place-values, while learning addition and subtraction. This is where potentially unfamiliar methods of learning could start to come into play.

Importantly, the standards do not dictate which methods or models teachers use. That’s a function of a school’s chosen curriculum. West Ada uses a curriculum called Engage NY, for example, which employs tools like number bonds and place-value charts.

“If you’re a first-grade parent, you can see why you might not be as familiar with the models they’re using to annotate those ways of thinking,” Carney said.

Educators say the point of these early-learning strategies is to help kids establish the foundation they need to truly understand the math algorithm that most parents learned. The goal is that students are comprehending the numbers, instead of just memorizing values, formulas and procedures.

“Once that starts to happen, once math becomes the thing you’ve only memorized … the wheels start to fall off,” Carney said. “You can only memorize so much and hold it well.”

Carney heads up Boise State’s Regional Math Center, one of a handful of such centers around the state that help teachers with math instruction. In the wake of the COVID-19 closures, they’ve developed a number of at-home resources, including an activity booklet (put together by the University of Idaho’s Regional Math Center), a Math Facts & Fluency website for parents and this video:

‘At the beginning, it was frustrating’

Statehouse critics have decried Common Core for years, and this year, lawmakers agreed to put together a committee to review and replace the standards.

Statehouse critics have decried Common Core for years, and this year, lawmakers agreed to put together a committee to review and replace the standards.

For Common Core opponents, math challenges have been a point of disdain. Idaho Education News asked parents about their experience helping kids with math during the COVID-19 crisis, and a few replied that they didn’t want to teach their kids “Common Core” math at home.

“Once we dumped the Common Core method and went back to the old math, it’s been a lot easier to teach and understand,” one parent wrote.

Honsaker almost gave up on teaching new math methods, too.

“At the beginning, it was frustrating. Like, ‘I’m not going to sit here and do this,” she said. Small addition problems took multiple steps to illustrate. Her daughter needed to show her work and solve one problem multiple ways.

A nagging conscience convinced Honsaker it was worth it. She looked up math tutorials on Google and conferred with Raegan’s teacher to make sure she was helping her daughter learn the right methods. West Ada also has tutorials on how to help with homework.

“It isn’t about me, it’s about her. I’m not going to be her teacher forever,” Honsaker said. “I need to figure this out. I can’t just be a Negative Nancy like ‘Nope, you’re going to learn this how I did.’ That’s not fair to her.”

Crook doesn’t fault parents for their confusion or frustration with elementary math.

She wasn’t familiar with the Engage NY math methods until three years ago. Now, she appreciates the methods because kids learn multiple tools to find the right answer, and can build on the strategies that work best for them.

When Crook explains this to parents, she thinks they understand it, too. She’s hoping that next year, at back to school night, she can take more time to teach parents about these math strategies early on. That communication is particularly crucial if students are going to continue with some form of distance-learning, she said.

“We have to be better at making sure what we’re teaching can be reinforced at home,” Crook said.