Do you want to know what school reopening might look like this fall?

Just look at what unfolded in the Treasure Valley this week.

Responding to an uptick in case numbers — and fearful of even bigger increases in the days to come — Central District Health clamped down on coronavirus restrictions in Ada County. But only in Ada County.

Expect more of the same. Expect everything to look different from community to community, from school to school.

And that’s by design. Three months after issuing a historic statewide stay-at-home order — and incurring the wrath of many of his fellow Republicans — Gov. Brad Little is turning the decision-making authority over to local health districts. After essentially shutting down public schools for the year in late March, Little’s State Board of Education will defer this fall to administrators and trustees.

Whether that’s a nod to local control — or just so much buck-passing — is in the eye of the beholder. Either way, Central Health District made the first big move Monday. Health officials knocked Ada County back to phase three of the state’s coronavirus guidelines, prohibiting gatherings of 50 or more people and shutting down bars that had been open for barely three weeks.

Mardi Gras in June. And the numbers didn’t leave Central District Health much of a choice. For weeks, Ada County’s infection rate was relatively stable, increasing by maybe a handful of new cases each day. From June 12 through Monday — a 10-day span — Ada County reported 429 new cases.

It gets worse, according to Ted Epperly, a Boise doctor who sits on the district’s governing board. Ada County’s positive test rates are approaching the numbers seen in Blaine County earlier this spring, when the county had one of the highest infection rates in the nation. Ada County’s potential rate of spread is also frightening; every one person with coronavirus has the potential to infect seven other people.

“You can get behind the eight-ball on this really fast,” Epperly said.

In the other three counties under Central District Health’s jurisdiction, it’s a different story. Boise County is one of nine Idaho counties that still have no reported coronavirus cases. Valley County has only four cases. Elmore County — the state’s 12th largest county, based on population — has 47 cases, ranking No. 15 in the state.

“We’re essentially dealing with Ada County,” Central District Health Director Russell Duke said during Monday’s news conference.

But there’s a catch to making local decisions about closing bars — or reopening schools. Decisions aren’t always consistent.

Consider this. From Friday through Wednesday, case numbers increased by 35 percent in Ada County. In Canyon County — just to the west of Ada County, but under the jurisdiction of a different health district — case numbers also increased by 35 percent over five days. Yet Canyon County continues to operate under stage four — with bars open, and no bans on large gatherings, including the Idaho Republican Party convention scheduled for this weekend.

Canyon County isn’t alone either. In the North Idaho panhandle, Kootenai County’s case numbers also increased by 35 percent over the same five-day period.

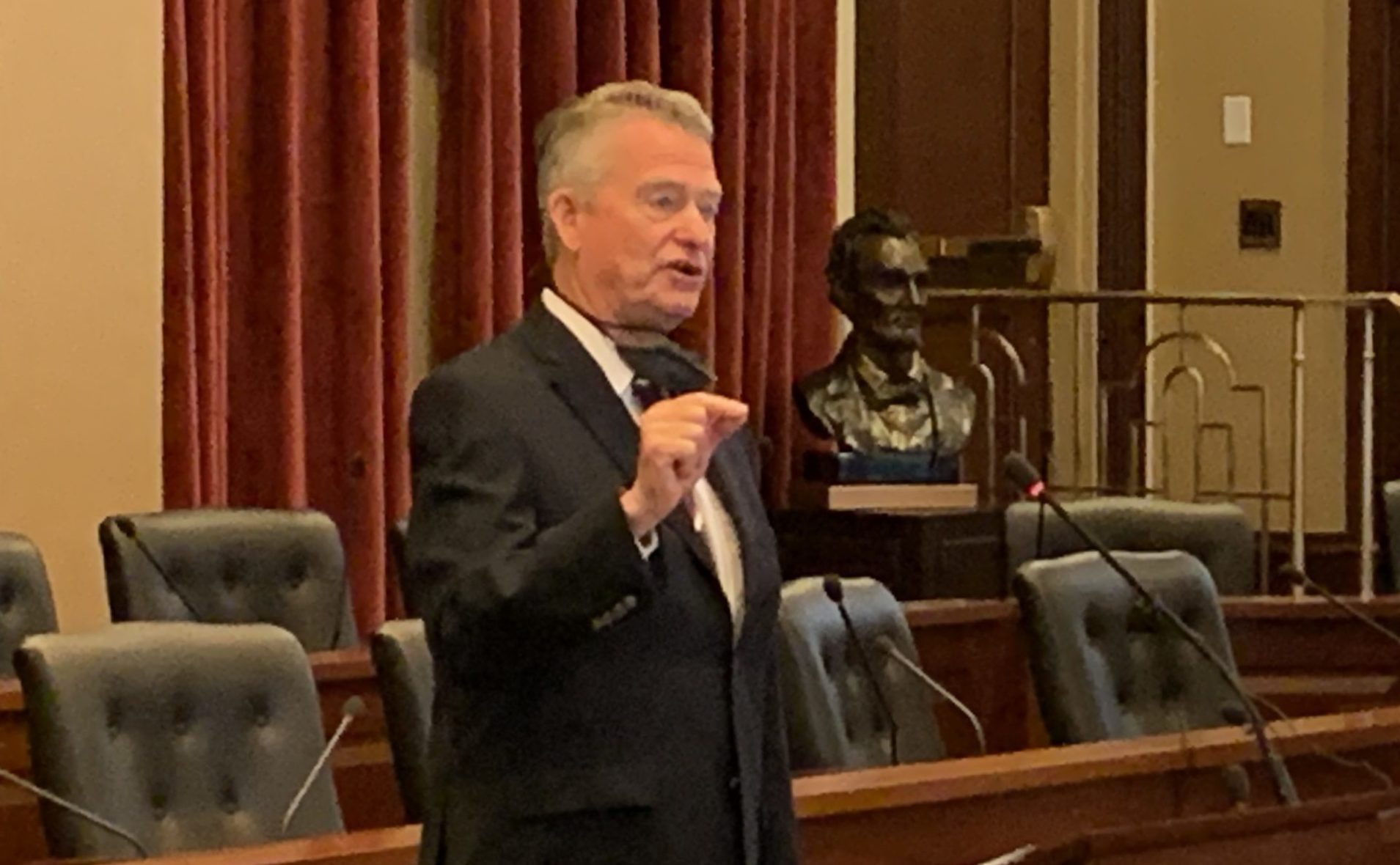

On Thursday, Little made one statewide move: With case numbers and positive test results increasing, he kept Idaho on stage four of its reopening plan, rather than relaxing guidelines on large events, restaurants and travel. But during a news conference, he also defended the transition to a localized approach, saying that has been his plan from the first days of the pandemic. Ultimately, he said, the state could step in and override a rogue health district or a mayor, but he’d rather it not come to that.

“We will continue to have a very robust dialogue with all of those entities … to make sure there is consistency,” Little said.

Consistency could be a tall order.

The state is putting a lot of power in the hands of seven health districts — and the local elected officials and the health care providers who make up their boards.

And that’s just the start. Come August, the state will place a lot of power in the hands of its 115 school districts and more than 70 charter schools. Their administrators and school boards will have the job of deciding whether to allow students into classrooms — and whether to keep their doors open if case numbers spike.

A gubernatorial panel is working on guidelines for school reopening, but they will be just that: guidelines. In a departure from state policy in the spring, superintendents and trustees won’t even need health district approval for their plans. This creates the potential for a patchwork of school policies within a tight geographic area.

No one knows exactly what school will look like in two months. But for better or worse — and on purpose — it will certainly look different from one district to another.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.