NAMPA — Children’s sweatshirts dangled from the fence around the duplex on the corner, their sleeves blowing in the October wind.

The two-car driveway was full, hinting someone might be home. But when Principal Chance Whitmore rang the bell, he got no answer.

A Rottweiler in the front yard barked tirelessly at the school administrators on his doorstep. Whitmore knocked. The dog paced. Whitmore knocked again.

West Middle School staff had visited this house before. The boy inside was expected to attend school this fall, but never finished the registration process. Calls to his family went unanswered. Then, weeks into the school year, his mother replied to an email.

West staff took the boy a laptop and set him up for classes. He made it to school online a few times, but when the school opened for hybrid learning in September, the boy missed repeated days of in-person instruction. Whitmore was at his house to see what was wrong.

Eight weeks into the school year, Whitmore and his administrative team were still knocking on doors, making sure they knew the whereabouts of every child they expected in classes this fall.

“There are a lot of worries if we can’t run down a student… Is the kid safe and warm and being fed? Are they getting educated?” Whitmore said. “Those are your hopes, but until you can confirm, you just don’t know.”

More than 11,600 students expected to return to Idaho’s public schools this fall never showed up, according to State Board of Education data.* That’s nearly twice as many as the average in years past.

These “no-show” students may have moved out of Idaho. They might be homeschooling or going to a private school that doesn’t report data to the state. Or they could have just stopped attending school.

Idaho’s lax and decentralized enrollment tracking makes it nearly impossible to tell, from a state level, where these students have gone, or if they’re completing the education state law requires for 7- to -16-year-olds.

Local school districts often have a better idea of where these children are — but sometimes they don’t. District leaders tell Idaho Education News that each year there are students who don’t show up, and families they can’t reach. Districts don’t have to tell the state, or a child welfare agency, which of those students they are never able to find.

The fragmented accounting system raises concerns about the oversight of mandatory education, and child safety.

“If we don’t know who has fallen through the cracks, how do we even know to look for them?” said Harold Nevill, CEO of the Canyon Owyhee School Service Agency in Wilder.

‘No-show’ students are at risk of falling through the cracks

Attendance is the backbone of Idaho school funding, so districts are quick to count their kids at the start of each school year. They expect to see some degree of turnover after the summer. In the Bonneville School District, for example, around 750 to 1,000 students leave each year and 1,000 to 1,300 new students arrive, superintendent Scott Woolstenhulme said.

Most students who leave are accounted for. Either they told the district they weren’t coming back, or the district got a student-record request from a new school, indicating that student enrolled elsewhere.

But that doesn’t always happen.

Some students don’t show up at the beginning of the year, and the school has no idea where they’ve gone. In those cases, Idaho leaves it up to each district to decide how far staff will go to track down that child.

This is different than a truancy situation, which happens if students stop attending during the school year. Unexcused absences typically prompt parent-administrator meetings, school discipline and even possible legal action against a parent. But because “no-shows” don’t ever start the school year, they don’t necessarily trigger these same procedures.

Idaho Education News spoke to school secretaries, principals and superintendents across the state about how they search for students who don’t return to school. All said they make some effort to reach families, at varying levels of intensity, and with varying levels of success.

Most school leaders call a student’s parents, then their emergency contacts. Sometimes they’ll do a home visit or send a school resource officer to check up.

“Districts are doing what they can with the resources they have,” said Karlynn Laraway, spokeswoman for the State Department of Education. “In the absence of something more specific in law, from the Legislature, I think districts are doing a lot.”

But educators can’t ever reach some families. Phone numbers change. Parents won’t answer the door when an administrator knocks. Or principals learn that a student doesn’t live at the address the school has on file.

There is no requirement that districts report these students to the state, or anyone else, for further follow-up.

Asked if Idaho needs a stronger accounting system to make sure these students are still getting an education, Laraway passed the question to lawmakers.

“That’s a question for legislators in balancing families’ rights to privacy and decisions about their children’s education — which the state values, you know, parent choice — and their obligation to inform schools,” she said.

‘No-show’ students could have moved, gone to work, or worse

As of late October, Vallivue School District administrators hadn’t been able to reach about 140 students. School administrators tried phone calls and sometimes home visits to reach these “no-shows,” said assistant superintendent Lisa Boyd. They didn’t hear back.

“There really isn’t a reporting process. It’s hard to decide — what do you do?” Boyd said. “We mark them in our system as a ‘no-show’ and we wait, see if someone calls us for their records eventually.”

The best-case scenario is that “no-show” students are learning from home, or have moved out of state, and records requests are delayed because of COVID-19.

They could also be working. Whitmore knows of middle-school students who have missed months of school to babysit siblings or help at a family business.

And they could have stopped attending school altogether.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit last spring, Mikala Stimmel decided she wasn’t going back to school at the Canyon Owyhee School Service Agency, or COSSA. Stimmel, 18, doesn’t want to take classes online. She’s working at a grocery store this fall and plans to test for her GED.

A few days into the school year, Stimmel says a COSSA staff member called her grandmother, to ask if Stimmel was going to school.

“I told her, ‘I’m not coming back,’ and then I kinda hung up on her,” Stimmel said. “She was going to try and talk me back into going there, and I was done.”

When a student doesn’t show up to COSSA in the fall, or leaves but doesn’t enroll in another district, Nevill’s staff will try to call them and sometimes make home visits. Staff members watch obituaries and county jail rosters for the students they worry about most.

Nevill has more than 30 students he considers “no-shows” this year, most of them super-seniors who didn’t finish school, but could still graduate. He knows some of them are in prison or working. He can’t reach the others.

“Does it concern us? Yeah. Not only on a human level, because you get attached to these kids and you wonder what happened to them, but we’re also accountable,” Nevill said. Students who “no-show” in high school can count against the school’s graduation rate.

COSSA has too many “no-shows” to chase each one, Nevill said. He focuses on students younger than 16, who are legally required to be in school.

Three months into the year, he’s still trying to find one 14-year-old. Nevill suspects the student, who has special education needs, is living in Boise with a relative. He doesn’t think she’s in school.

“It is certainly concerning that a special education student, who needs specialized help, is not getting that help,” he said.

In the worst-case scenarios, missing students could be in trouble: facing a crisis, or experiencing abuse or neglect at home.

“Once in a while there’s a kid who is really in trouble, really in trouble at home as a victim of physical or sexual or emotional abuse, and schools are their best chance of hope,” said Jodi Heilbrunn, director of the National Center for School Engagement.

Idaho has some of the most lax homeschool tracking in the nation

A lack of state data on homeschool students contributes to the confusion about where “no-shows” have gone.

Idaho is one of only 11 states that doesn’t require parents to notify anyone if they decide to homeschool, according to the Home School Legal Defense Association. Even among those states, Idaho’s requirements are slim.

Indiana requires a minimum number of homeschool teaching days. Missouri requires parents to keep records of children’s work. Idaho’s only requirement is that homeschool parents teach “subjects commonly and usually taught in the public schools.” Idaho “does not regulate or monitor homeschool education,” the SDE’s website says in bold.

Idaho has no count of how many students are homeschooled across the state, making it difficult to say if “no-show” students have decided to learn from home. The state similarly does not regulate, or collect data on private school enrollment.

Idaho’s compulsory education law makes parents responsible for ensuring their child is educated. The SDE champions parents’ “freedom to chose the method of education that will work best for their children.”

But the state’s failure to collect data on non-public school enrollment leaves leaders without a comprehensive understanding of which educational options parents are choosing, or a means to track children who leave the public school system without telling schools where they’ve gone.

State Board of Education President Debbie Critchfield says COVID-19 has put a new emphasis on how Idaho accounts for students.

“It really has highlighted that we don’t have mechanisms in place, whether in a system for the state, or a local protocol, outside of what (districts) have done year to year,” Critchfield said.

“If we’re looking for positives during this pandemic, this really opens up a discussion on: Where are students year to year? Students that don’t come back — why is that?”

Other states have developed more infrastructure

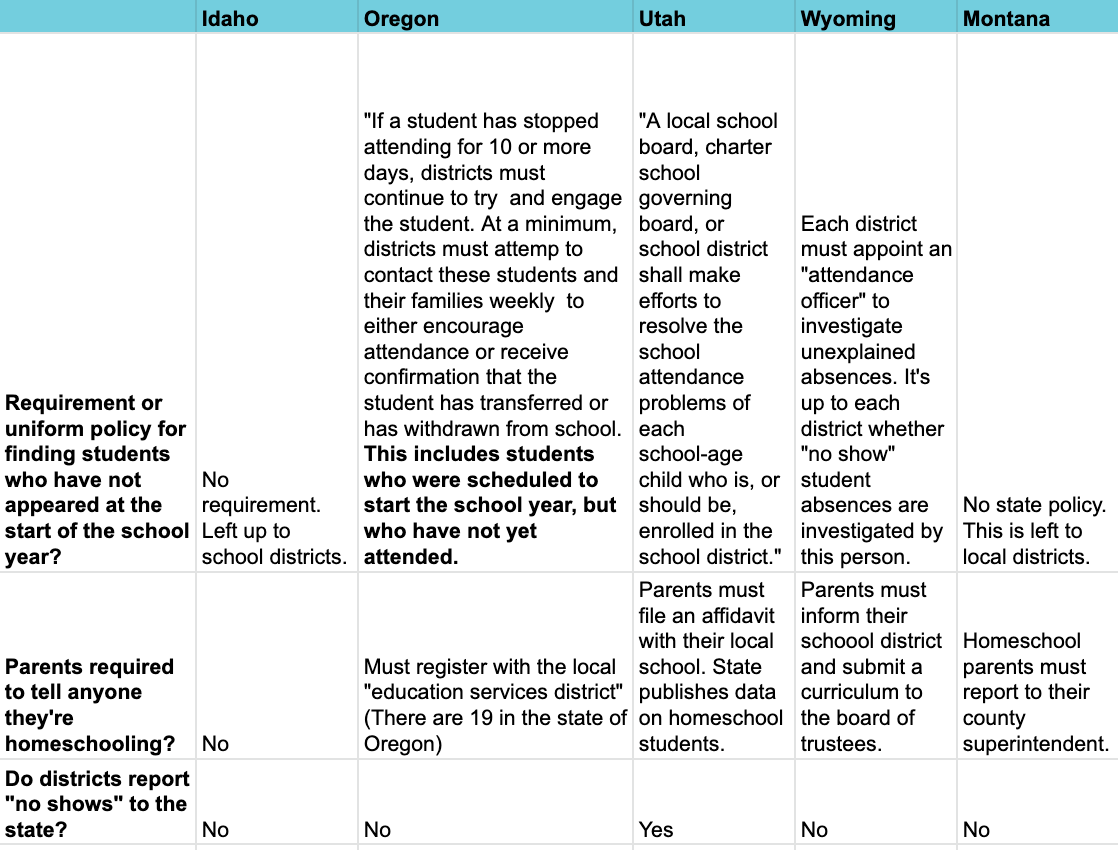

Most of Idaho’s neighbors don’t require local schools to report “no-show” students. However, they all require parents to notify officials if they intend to homeschool.

Some states offer explicit guidelines for tracking “no-show” students.

Arkansas requires districts to assemble a diverse school outreach team to review “no-show” data and, do home visits and communicate with parents about what resources they might need.

Oregon asks schools to reach out to “no-shows” once every week “to either encourage attendance, or receive confirmation that the student has transferred or has withdrawn from school.”

In the absence of state policies, each Idaho district determines how to find its “no-show” students.

Weeks of outreach efforts pay off for Nampa educators

Whitmore, in Nampa, started the year with about 25 “no-shows” in his 600-student middle school. District leaders asked staff to keep trying to find these students, given the challenges families could be facing with COVID-19.

That’s standard practice at West, where three-quarters of students are low-income. Administrators work to keep up with families who move frequently if parents change jobs, change housing, or go to jail.

So, when a little boy in a corner duplex didn’t show up for school this fall, administrators kept reaching out until his mother replied. And on a blustery Monday in October, two months into the year, they waited for five minutes on her stoop until the woman came to the door.

The boy’s mother had been working a new night shift, she told administrators. She lost track of the days her son was supposed to be in school. But thank you so much for coming by.

“Have a great day,” Whitmore called to the family as he piled back into his red Ford pickup and went to find the next student.

Sometimes parents are grateful that the district is checking up on them, Whitmore said. Some are upset that administrators came to their homes. Others won’t open the door.

With weeks of repeated home visits, and the help of district SROs, West Middle School staff found out what happened with each of the two dozen “no-shows” on the fall enrollment list. They continue to follow up with students who have spotty attendance.

After a second stop, the administrators drove back toward West hopeful, but uncertain of the fruits of their efforts.

“If he gets off the bus and comes to school on Thursday… it’ll be mission accomplished at that point,” Whitmore said. “If not, we’re back to square one.”

*A note on methodology: Idaho does not require districts to turn in a number of “no-show” students. The 11,600 students referenced in this report represents the number of students who were expected to return this fall, subtracting the number of students who actually had returned to schools by Oct. 30, 2020. The data was calculated by the State Board of Education at Idaho Education News’ request.