In a news release sent to reporters last month, Idaho Education Association president Layne McInelly called on Gov. Brad Little to funnel a record $900 million surplus into education spending. The union wants smaller class sizes, less reliance on bonds and levies and, importantly, more mental health support personnel.

“Idaho schools are woefully short on counselors and psychologists at a time when students need support for mental and emotional health more than ever,” McInelly wrote in the news release.

Idaho’s ratios of school counselors and psychologists per student are far below staffing levels recommended by national organizations, as are the state’s ratios of other pupil service staff, such as school nurses and social workers.

According to a recent State Department of Education report to the federal government, Idaho has:

- 403 students per school counselor. The recommended ratio is 250 to 1.

- 1,704 students per school psychologist. The recommended ratio is 500 to 1.

- 1,825 students per school nurse. The National Association of School Nurses used to recommend a ratio of 1 nurse to every 750 healthy students, and higher ratios for students with more complex needs. (The association currently says that using a ratio of student-to-nurse alone is “not evidence-based or appropriate.” EdNews will use the student-to-nurse ratio for the sake of consistency with our other calculations.)

- 5,822 students per school social worker. The recommended ratio is 250 to 1.

*Note that the current ratios count part-time and full-time positions, and do not include professionals who are contracted through outside vendors to work with school children.

So, what would it cost to fully staff all of these positions?

EdNews used Idaho average salaries (and an additional 20% for benefits) to calculate how much it would cost to staff these four positions to the recommended levels.

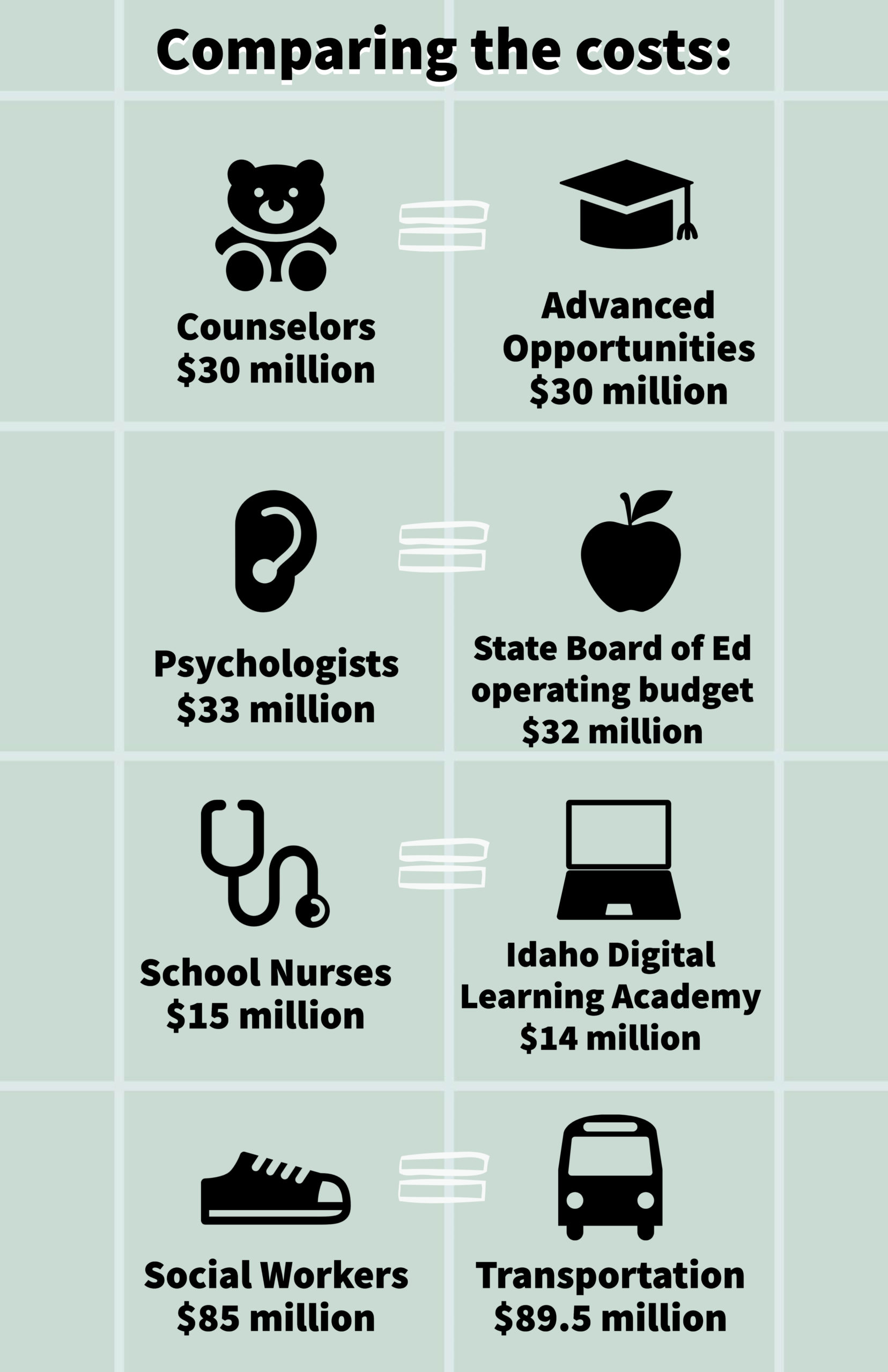

By our math, it would cost roughly:

- $30.5 million to reach the recommended ratio of staff school counselors, who had an average salary around $54,437 last year.

- $33 million to reach the ratio of school psychologists, at an average salary of $63,413.

- $14.8 million to staff school nurses to the 1-750 ratio. Nurses make an average of $51,176 a year.

- $85 million to reach the suggested ratio of school social workers, whose average salary is about $60,166.

Added together, reaching recommended ratios for all of the positions would cost more than $160 million a year.

(The State Board of Education estimates it would cost closer to $126.5 million, if each position cost $46,415, which is the average career-ladder payout for pupil service staff.)

Greg Wilson, education advisor for Little, says boiling the issue down to dollar signs and ratios overlooks two key issues: Idaho’s challenges finding qualified professionals for these spots, and local control.

“We have a recruiting and retaining challenge for a lot of different positions within a school district,” Wilson said. Urban districts in places like the Treasure Valley likely have an easier time finding and hiring school psychologists, he said, than Idaho’s smaller and more remote districts.

Hiring decisions are also up to local school administrators. Even if state leaders decided to invest in getting these ratios in line, “it wouldn’t necessarily be a sure thing that would happen,” Wilson said. Districts decide who to hire with career-ladder funds, and where one district might hire a school nurse with more state money, another district might decide to use the money for a different staff position.

Wilson said the governor’s commitment to funding the career-ladder salary schedule for Idaho educators was a step toward helping districts recruit professional educators and support staff, and that supporting student behavioral health is an ongoing objective for Little.

“I think what we can do is continue to kind of push it as a priority,” Wilson said.

McInelly agrees that Idaho districts wouldn’t be able to hire all the nurses and psychologists and social workers they needed in one fell swoop — “but we need to start working on that,” he said. “Until we have the money to hire these people, we don’t know how short we will be staffed.”

Tracie Bent, chief planning and policy officer for the State Board, raised another complicating factor in Idaho’s method of funding pupil service personnel.

Currently, Idaho’s “staff allowance” for pupil services personnel (the category of school staff which includes counselors, psychologists, nurses and social workers), doesn’t allocate enough money to reach these ratios.

Districts are funded for about .75 full-time pupil service staff per “unit” of students. (A unit is basically a batch of students counted together for the purpose of funding).

To reach the recommended staff ratios in all four of these categories, Idaho would need to hire 2,272.58 more full-time equivalent staff, Bent said.

That would take increasing the per-unit staff allowance to 4.65 — which would require the Legislature to make a change to Idaho code.

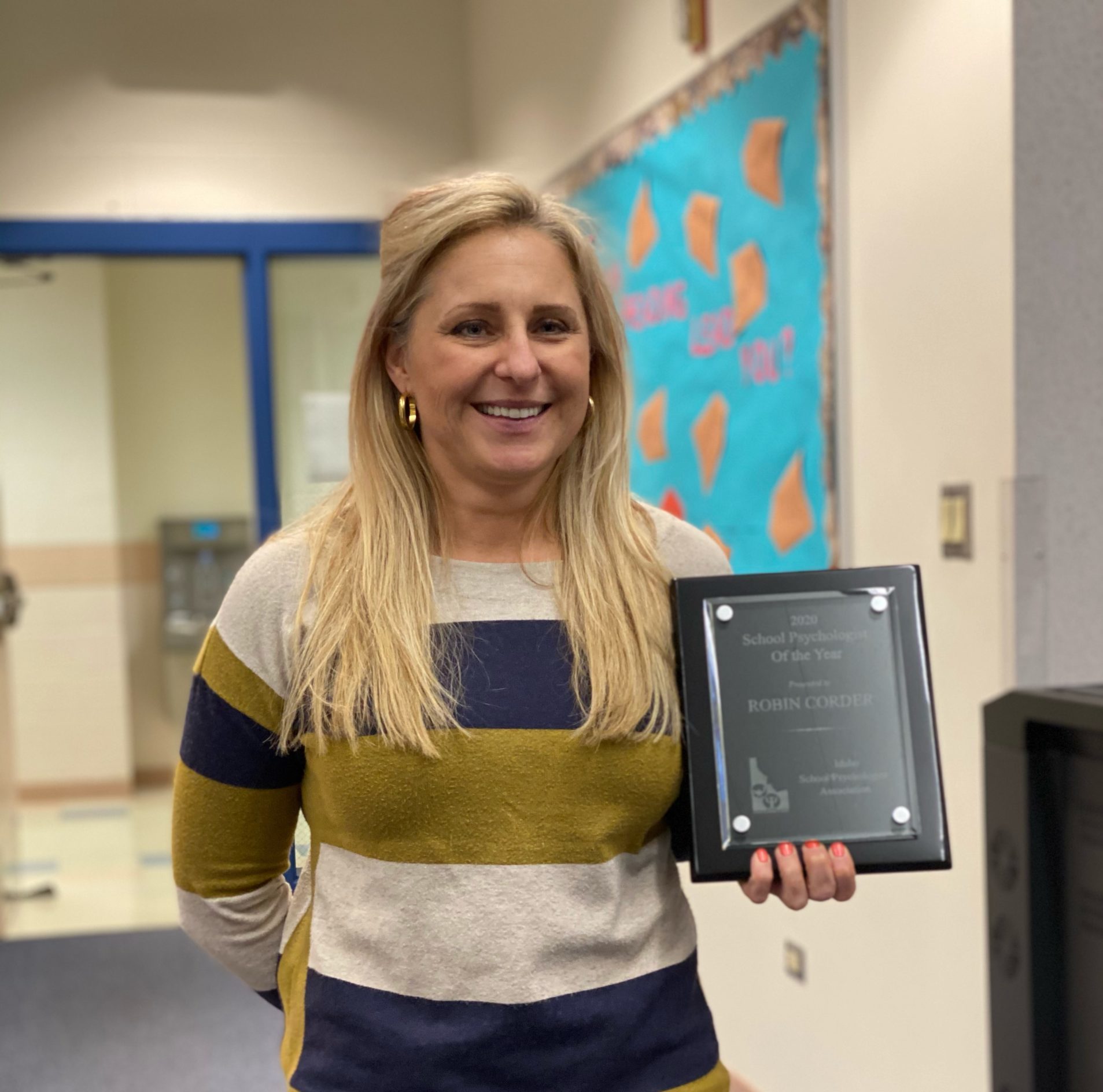

“If you’re going to try to (reach the ratio) for one, you probably should do it for all,” said Molly Strauss, president of the Idaho School Psychologist Association.

Strauss thinks Idaho schools would have an easier time finding school psychologists if the student counseling workload was attractive to potential applicants. One of her association members is the only psychologist for 3,000 students, Strauss said, and is overloaded with just assessing students. With those kinds of ratios, Strauss said school psychologists can’t do the proactive work, like academic interventions, group counseling and collaborating with teachers and families that helps mitigate student issues before they escalate.

“We’re missing the whole preventative piece of our job, because we are just trying to stay afloat,” Strauss said.