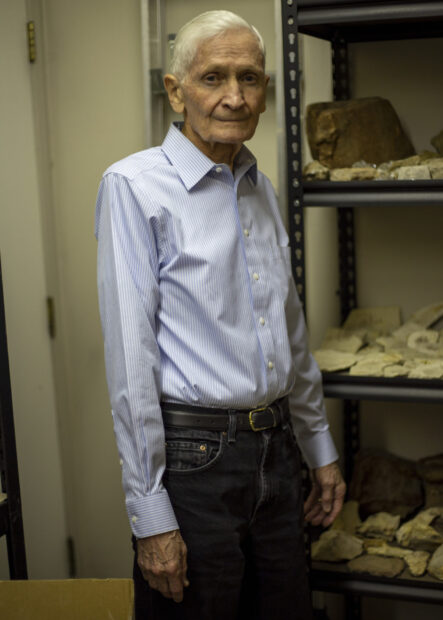

Jim Jones was an Idaho farm boy who went from the trenches of Vietnam to a prominent state attorney before leading Idaho’s highest court.

On the verge of his 80th birthday, the former judge is retired, but he’s not slowing down.

For months, Jones has been battling the Idaho Freedom Foundation, a bold conservative lobbying group under scrutiny for its tactics and influence.

He’s also a leading voice of a new group bent on challenging lawmakers who do the Freedom Foundation’s bidding at the Statehouse.

It’s a fight Jones refuses to sit out because, for him, it’s about preserving education and democracy. And as he sees it, retiring has opened the way for saying things he kept “bottled up” for years as a judge.

“I’m damn tired of it… sick and tired of it,” he told EdNews of the Freedom Foundation’s tactics and influence at the Idaho Capitol.

‘A bolt of lightning’

Growing up on a farm in Eden in the 1950s, Jones reflected on his future at a young age. By middle school, he knew what he wanted — or thought he did.

Hearing his Uncle Randy, an engineer and an “ideal” figure for Jones, tell of his time building bridges in Afghanistan, Jones decided to follow suit. It felt “exotic” and it felt right, he recalled. Plus, he was good at math, so engineering made sense.

After high school, he enrolled in an engineering program at Idaho State College in Pocatello. Then he heard John F. Kennedy’s inauguration speech, which changed everything. Jones recalled the date, Jan. 20, 1961, and the President’s famous appeal for Americans to “ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country.”

“It was like a bolt of lightning,” Jones recalled.

Kennedy’s request put Jones on a different path. Instead of building bridges in Afghanistan, his pursuits would take him to Vietnam and a career in public service in Idaho.

But he had other plans first.

The would-be senator

Reflecting on Kennedy’s life, Jones noticed themes. The president was a prior U.S. senator. His election opponent, Richard Nixon, had followed a similar career path.

Jones didn’t want to be president, so he set his sights on the U.S. Senate.

There was another theme in Kennedy’s life: military service.

While at Idaho State, Jones applied for the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps, which was then a requirement for young men. But a car crash in high school had left both of his legs broken — and one inches shorter than the other. The injury barred him from joining.

Disheartened but undeterred, he again changed course, dropping engineering for the University of Oregon’s political science program — a better fit for law school, he thought, and, maybe, a second swing at ROTC membership.

He walked into the Eugene, Ore.-based campus’s ROTC office and signed up, this time keeping the accident and his injury under wraps.

That Senate seat felt one step closer.

Changing views

Jones earned his political science degree in 1964 and enrolled in law school at Northwestern University.

He had changed. Time on both campuses was politically eye opening, he said, recalling an “embarrassing moment” when a University of Oregon professor criticized a speech he gave on disgraced former Army general Edwin Walker.

“I was spewing out a lot of right-wing crap,” said Jones, adding that he still left Eugene a Republican, despite more moderate views and a pledge to consider issues more broadly.

His grasp on the U.S. Senate and the divisiveness of American politics was also emerging. The summer before law school, he interned for U.S. Sen. Len B. Jordan and helped with Jordan’s “hot-and-heavy” political campaign.

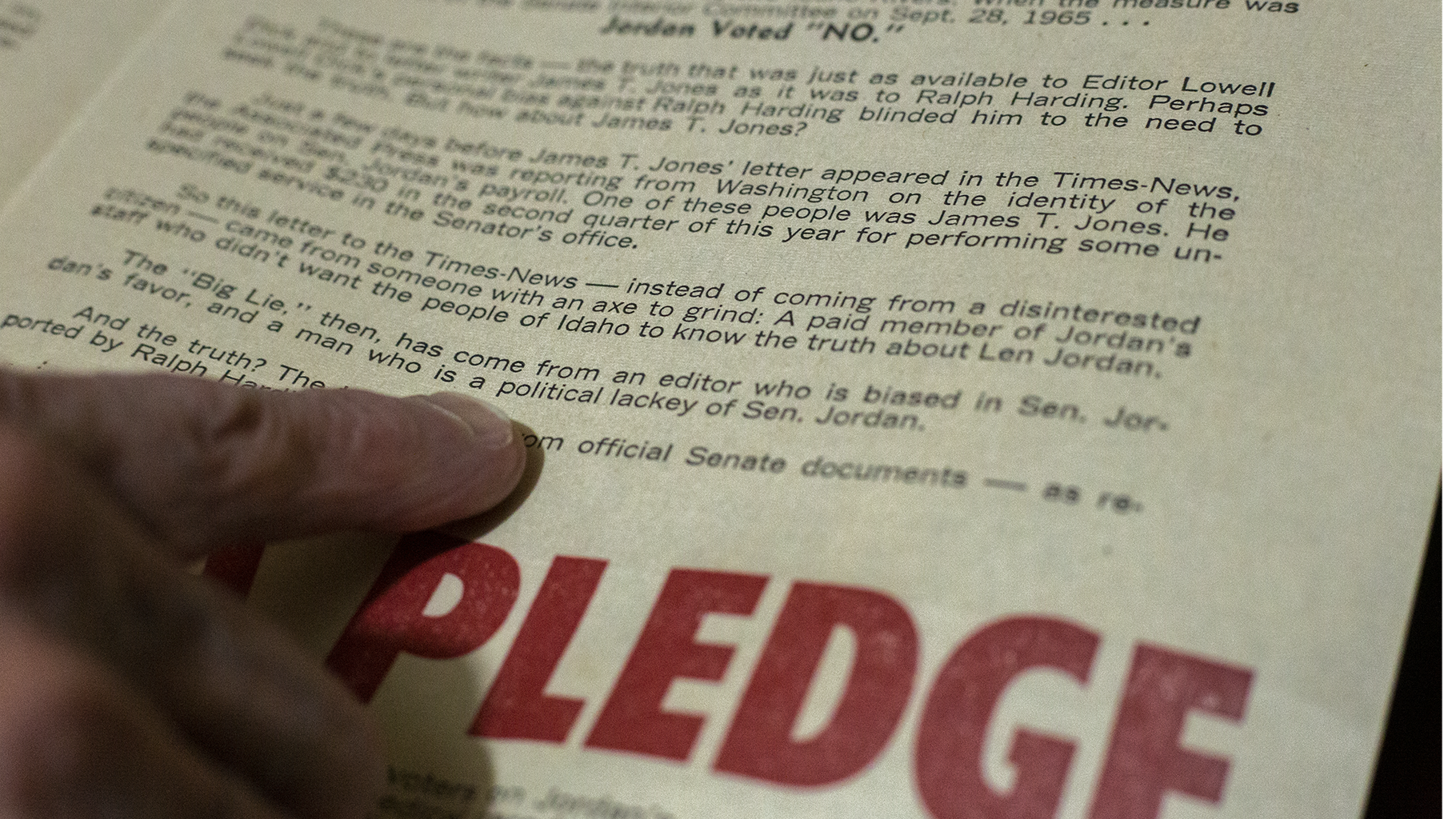

“I knew he wasn’t telling the truth,” Jones said of campaign rhetoric from then-congressmen Ralph Harding, a Democrat challenging Jordan’s Senate seat by attacking his campaign finances.

Jones ran an op-ed in the Twin Falls Times-News defending Jordan — and garnered an unexpected response. A full-spread ad in the paper soon after painted Jones as a paid “political lackey” lying for Jordan. Jones flashed a photo of the ad, which he keeps in a file at home and on his cell phone.

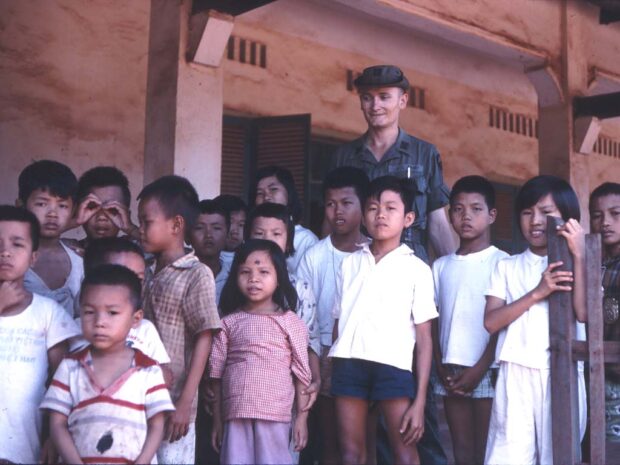

Jordan regained his Senate seat, but Jones would have to wait years for his own run. He finished law school in 1967, went on active duty in the Army and volunteered for combat duty in Vietnam’s Tây Nihn Province, where he worked as an admin officer in aerial artillery, mostly “pushing papers.”

He had a law degree, but his military focus was on big guns. He recalled the hydraulic lift needed to load the 200-lb. bullets that ripped through the jungle. “I’ve had hearing problems ever since,” he said, pointing to his ear.

Two things drove his path toward artillery, despite having a law degree: he was “good at math” and the military program for lawyers, Judge Advocate General Corps (JAG), required four years of service, rather than the two needed for artillery.

“I wanted to get military experience, not make a life out of it,” said Jones.

Still, Vietnam changed his life. He went on to publish a book, “Vietnam, Can’t Get You Out of My Head,” which recounted his 407-day tour flying over the province, calling in artillery on suspected Viet Cong operations, living and working with South Vietnamese forces and helping at a church-run orphanage that communists shuttered after the war.

There were high points. Jones recalled a Christmas party for orphans, where he handed out umbrellas for local women. He reunited with one woman who remembered him as “the guy with the umbrellas,” in 2018.

His work at the orphanage earned him an Army Commendation Medal. He was honorably discharged as a captain in August of 1969.

The war would also play a part in his eventual departure from the Republican party.

From AG to judge

After another stint in Washington, D.C., assisting Sen. Jordan, Jones moved back to Idaho in 1973 to practice law in Jerome and prep for his long-awaited Senate run.

It came in 1990, but he lost to then-U.S. Rep. Larry Craig.

Congressional election failures had by then plagued Jones, who lost two prior runs for the U.S. House in 1978 and 1980.

He ran for Idaho Attorney General in 1982, and won. He was AG for eight years. It wasn’t Congress, but issues of the time were potent, and marked some of his most notable work, including arguing before the U.S. Supreme Court shortly after his election and leading a landmark settlement with Idaho Power that shaped use of the state’s water resources for decades to come.

The water battle brought Jones back to his prior political work for Sen. Jordan. Teaming up with Idaho Falls native Bruce Newcomb, who would later become Idaho’s House Speaker, he led an effort to unseat lawmakers who supported Idaho Power.

“Our message was if you support the power company, we’re coming after you,” Jones said, casting the approach as a precursor to his latest efforts with Newcomb to rid the GOP of the Idaho Freedom Foundation’s Statehouse “acolytes.”

After two terms as AG, Jones returned to his private practice in Boise for 15 years before gaining a seat on the Idaho Supreme Court in 2005. He ran unopposed in 2010 and became chief justice in August 2015 by a vote of his peer justices. He retired in 2016.

“I figured 12 years was enough,” he said of his time on the bench.

He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer two weeks later.

‘Take Back Idaho’

Five years later, Jones says he’s cancer free — and ready to take on the Idaho Freedom Foundation, and its “assault on education.”

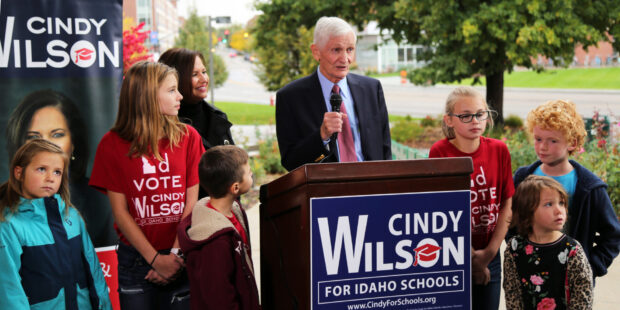

Along with Newcomb, Jones and other former Republican office holders recently formed Take Back Idaho, which aims to redirect Idaho’s GOP from the “sad state of affairs of a once-admired party.”

Jones spearheaded the effort last year by organizing a Zoom meeting with several leaders who share a distaste for the Freedom Foundation’s influence.

“(Jones) is like the Energizer Bunny,” said Jennifer Ellis, a Republican, Blackfoot rancher and the group’s newly named president.

Other notable names have since joined the ranks:

- Former state Senate leader Bob Geddes

- Former Secretary of State Ben Ysursa

- Former State Treasurer Lydia Justice-Edwards

- Former school Superintendent Jerry Evans

Public education is a main focus for the group and for Jones, who described his efforts as “saving the schools” from the Freedom Foundation, which has ramped up its criticism of public education in recent years, decrying public educators as peddlers of social justice indoctrination and critical race theory.

In 2019, Freedom Foundation president Wayne Hoffman argued that government shouldn’t be in the education business. Last year, Republican lawmakers who often echo the Freedom Foundation’s talking points at the Statehouse led the way in tanking a $6 million federal early childhood education grant that would have helped cover preschool costs in communities across the state and given childcare relief to working parents.

Jones last month jumped headfirst into the debate, publishing a column introducing Take Back Idaho and blasting the Freedom Foundation for the “sorry state of Idaho politics.”

“By coddling receptive legislators and punishing those who don’t heed its orders, IFF has established a firm grip over the votes of too many GOP legislators,” he wrote.

Ellis told EdNews that Take Back Idaho is still gauging candidates to support — and oppose — with a historic May primary capable of reshaping the state’s political landscape approaching.

“There are tons of candidates, so we’re still assessing,” she said, emphasizing the group’s eye on defeating those in line with the Freedom Foundation.

Jones keyed in on one lawmaker. In a recent interview with EdNews, he pointed to Rep. Ron Nate, a Rexburg Republican who this session tried to cut more than $1.3 million from the state’s higher education budget, citing nearly dollar-for-dollar breakdowns and language compiled by the Freedom Foundation. The Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee voted Nate down.

Meanwhile, Freedom Foundation leaders have hit back at Jones and his group. The day after Jones’ February column ran, Hoffman accused him of lying.

“Isn’t it interesting how leftists will straight up lie to you about issues you care about in order to win popular support?” Hoffman wrote.

The Freedom Foundation does not respond to media inquiries, but other attacks on Jones have surfaced. Freedom Foundation board member and Bonneville County Republican Committeeman Doyle Beck lumped Jones into a list of Take Back Idaho “Rinos” — Republicans in Name Only.

Jones doesn’t hide his disassociation with the Republican party. He remembers the year, month and reason for breaking ranks. It was August of 2002, following false claims from Republican leaders of weapons of mass destruction as a justification for the Iraq war. His time in Vietnam, and justifications for war there, contributed to his decision to leave the party, he said.

Jones, who now calls himself an Independent, dismissed Hoffman’s column, but found amusement in it.

“If you provoke Wayne, you’re liable to get some really wonderful Gems,” he said with a smile.