Months into the school year, K-12 leaders at dozens of school districts and charter schools across Idaho say they’re struggling to fill positions for teachers and other staff.

And many are experiencing higher rates of teacher turnover than usual.

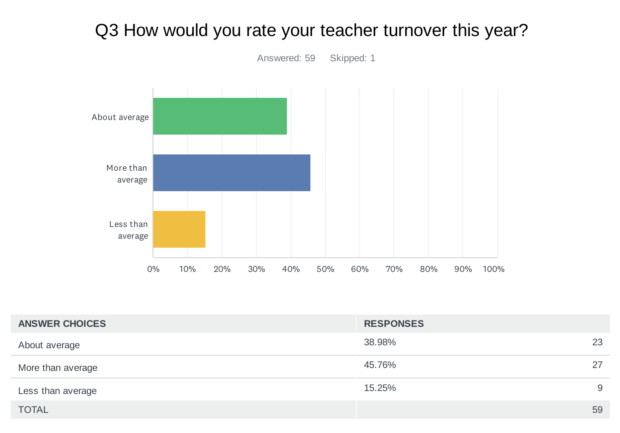

Twenty-four of 36 administrators recently surveyed by EdNews say they still have teacher openings in their districts. Of the same respondents, 27 rated their teacher turnover this school year as “more than average.”

The survey follows two tough pandemic years and a slew of lingering concerns from teachers about their profession. Most teachers returned to their classrooms this school year but point to a range of issues, from feeling underpaid and disrespected to being overworked and unsatisfied.

And with teacher attrition a constant struggle for administrators hoping to keep classrooms staffed, some schools are facing steeper shortages in certain content areas — and turning to alternative teacher authorizations and four-day school weeks for respite.

Some open positions are typically harder to fill than others, but local leaders say a range of problems, from a retirement uptick to unusual job mobility, augment the challenges.

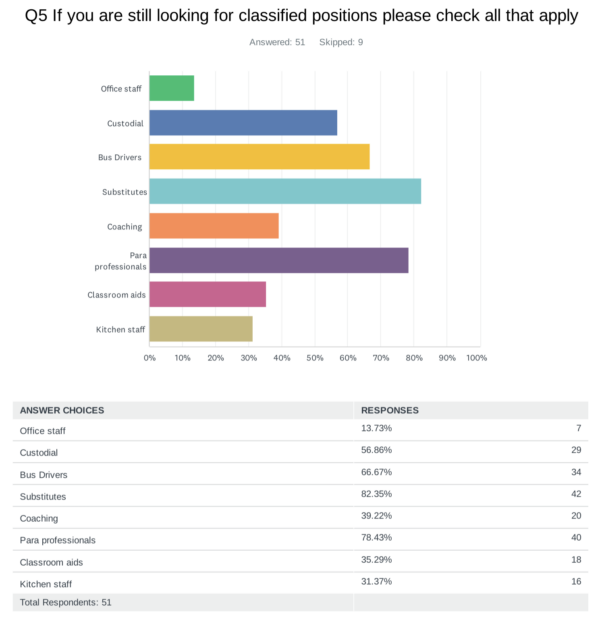

On top of that, filling other classified positions, from substitute teachers and bus drivers to janitors and paraprofessionals, is even a bigger struggle for schools, and that’s impacting teachers’ views about their own jobs.

“Our biggest challenge is filling paraprofessional positions for special education,” Bonneville superintendent Scott Woolstenhulme told EdNews. “This has led to an escalation in student behaviors, which is impacting the learning of students and the morale and effectiveness of teachers.”

By the numbers: What administrators are saying

On top of a slew of teacher openings across Idaho, just nine of 60 superintendents surveyed said their teacher turnover was less than average this school year.

Fifty of 59 said it was at or above average:

Meanwhile, 51 of the 60 superintendents surveyed pointed to openings among classified staff, where substitutes, bus drivers and paraprofessionals are in extra high demand.

Click here for the full results of our survey.

What gives?

Twin Falls School District Superintendent Brady Dickinson sees several problems.

Months into the school year, his district of 9,410 students is still searching for three fourth-grade teachers, teachers for 3.5 special education positions, a reading and a math teacher.

A staff member’s sudden passing left the district scrambling to fill one of those openings, Dickinson said, but the others are typically hard to fill.

And for Dickinson, that’s part of a broader problem: some positions are simply trickier to fill than others — and have been for years.

Fourteen of the 60 districts EdNews surveyed pointed to vacancies in special education — an area schools, including those in Twin Falls, typically struggle to fill.

But Dickinson also sees problems with the teacher pipeline in Idaho: “There simply are not enough teachers coming out of university pipelines to fill the positions left open by educators retiring, leaving the profession or relocating.”

Schools are leaking teachers faster than they can replace them, EdNews recently found.

And then there’s the surge in job mobility across the country. Many Twin Falls educators are relocating to different areas when their spouse or family member finds employment elsewhere, Dickinson added. The upsurge in home prices in and around Twin Falls has made it “increasingly challenging” to attract educators to the area.

Nampa interim superintendent Gregg Russell agreed. Nampa is another larger district with numerous teacher openings: 13 currently, from special education to science.

The district has for years “struggled with finding teachers in various disciplines like math, science, and special education,” Russell told EdNews. And higher housing prices in Ada and Canyon counties haven’t helped. For Russell, income for educators plays a big part: “Teacher pay typically does not match that of other careers with a professional licensure, and the difficulty of the job.”

Russell also pointed to a baby-boomer retirement wave — something he sees as a both a state and national issue.

Still, more districts are having a hard time hiring classified staff than teachers, from bus drivers and substitute teachers to paraprofessionals and janitors.

Administrators say the struggle for classified staff boils down to funding.

For Bonneville, that doesn’t necessary mean more funding, just more flexibility tied to funding.

“We do not necessarily need more state funding to address our staffing issue, especially with the additional $300 million approved in the special session,” Woolstenhulme said. “What we absolutely need is to be given more flexibility by the Legislature in how to use the dollars we are given.”

West Side School District Spencer Barzee said to ease the challenge in his schools, classified employees would need to see a 30% to 40% increase in their paychecks.

West Side has no teacher openings at the moment, but classified openings exist for office staff, custodians, bus drivers, substitute teachers, paraprofessionals, classroom aids and kitchen staff.

Schools scramble to adjust

Barzee credited one thing for filling all teacher positions in his district this school year: dropping a learning day from the calendar.

“The primary purpose for our district transitioning to the four-day school week was for the recruiting and retention of teachers,” he said of his district’s recent decision to drop Fridays from the calendar.

Three years into the change, Barzee said it gives school districts like his an “advantage over industry for recruiting and retention.”

Four-day weeks have spread rapidly across Idaho in recent years. As of September, 81 of 186 Idaho districts and charters had made the switch. The number has more than doubled since 2012-13, when only 39 districts had a four-day schedule.

The hope, administrators say, is that this will encourage teachers to apply for jobs.

But districts opting for four-days are largely smaller and rural, like West Side. Bigger districts have come to rely on another primary means for making sure classrooms stay staffed: alternative teacher authorizations.

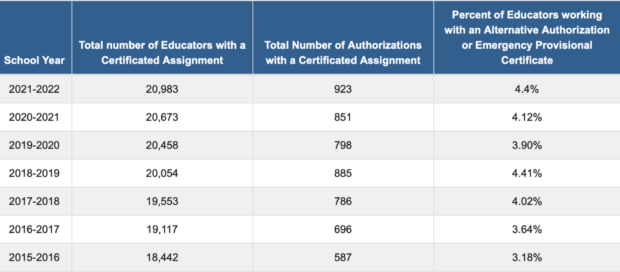

Idaho allows would-be teachers to become fully certified teachers through alternative programs like Teach for America and the American Board for Teacher Certification. Districts can also hire teachers on an “emergency provisional” basis, which puts a teacher in the classroom before they complete their certification.

Here’s a look at how the number of Idaho teachers who pursue these routes to the classroom has increased over the last seven years.

Administrators say the flexibility is good, and bad.

“We would not have been able to fill all of our teaching positions without the use of alternative authorizations and emergency provisional authorizations,” Dickinson told EdNews.

Russell called alternative authorizations a “given necessity” for filling Nampa’s teacher positions.

But drawbacks include streamlined training and the need for enhanced professional development, both administrators said.

“These educators come without the traditional education background,” said Dickinson, “which requires extra training and support while they are on the job.”

And that demands a “much more robust professional development and instructional coaching program,” which are beneficial for all educators in the district but do require additional resources.

Russell said: “A larger burden falls on the district to ensure quality mentors support those folks and (that) the district provide further training around the nuances of teaching.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this story.