The next time your child heads to the pediatrician for a checkup, the doctor’s tools are likely to include more than just a tongue depressor, reflex hammer, and stethoscope.

This time, a questionnaire about depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation might be among them too.

Nationwide, professional organizations are calling for primary doctors and pediatricians to regularly screen adolescents for mental health issues. Last month, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended for the first time that primary care doctors screen all children 8 to 18 for anxiety, and reaffirmed its guidance to screen children ages 12 to 18 for depression.

It’s not the only national group to adopt that stance; the American Academy of Pediatrics started recommending mental health screenings for adolescents in 2018. And Regence BlueCross BlueShield insurance made a similar recommendation to providers several years ago as well.

The change speaks to the increasing need for mental healthcare among American adolescents – and Idaho’s kids are no different.

Professionals in the classroom, the doctor’s office, and insurance agencies are all noticing an uptick in depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation among young Idahooans – but they’ve got ideas for how to help.

Shifting to holistic healthcare, providing better support for patients in need of mental health services, and offering remote mental healthcare for rural K12 students are some.

Shifting to holistic healthcare

Alicia Lachiondo, the associate medical director of general pediatrics for St. Luke’s Health System, said she’s been having more conversations with kids about mental health issues than ever before in her career.

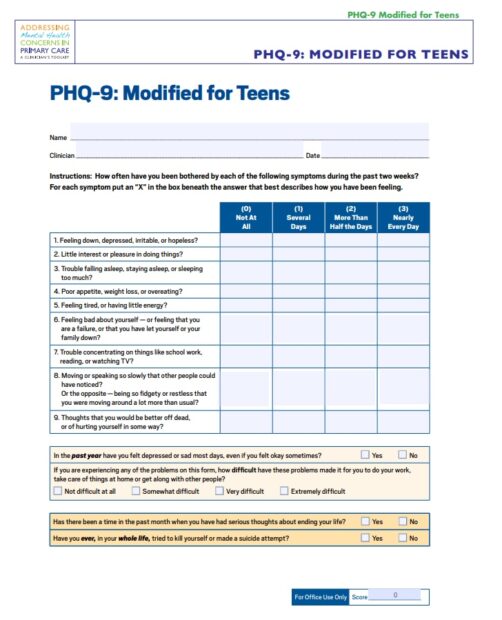

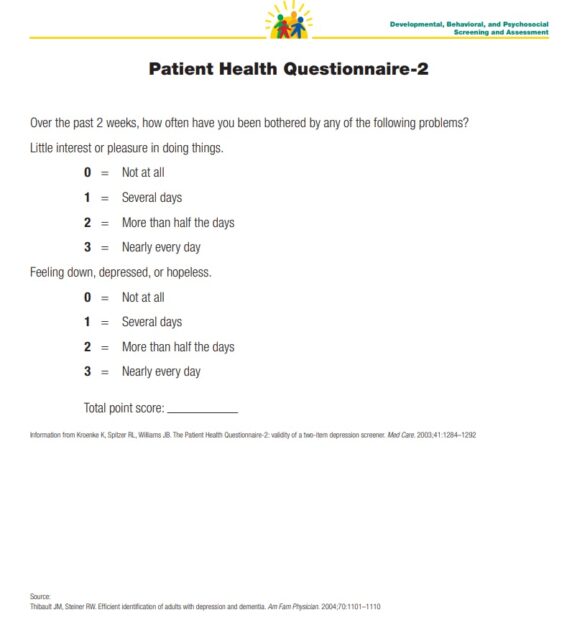

At St. Luke’s, pediatricians regularly screen children 12 and above for depression and suicide using common questionnaires (see below).

The older kids answer the questionnaires on a device, and then Lachiondo discusses their answers with them. She usually asks to have that conversation without parents present so kids feel free to be honest.

“It can uncover some feelings that kids haven’t talked to an adult about yet,” Lachiondo said.

She then encourages those kids to talk with their parents about what they’re feeling. If the questionnaire does signal mental health needs, Lachiondo might take a number of steps, from encouraging kids to decrease screen time to referring them to mental health professionals.

She involves parents in the next steps as well, so it is a shared decision-making process.

For kids under 12, Lachiondo will have discussions with them about anxiety and depression if their parents have brought them in due to behavior or mood concerns.

“More and more kids are coming in at 9, 10, 11 with concerns,” Lachiondo said. “Just today an 11-year-old was talking about depression and anxiety.”

Lachiondo attributes the rise in mental health needs to a number of factors, including Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), such as: experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect; having a family member attempt or die by suicide; or growing up in a home with substance use problems, mental health problems, or instability.

The pandemic has exacerbated existing issues as well.

“Caregivers and teachers have lost resilience and struggled, so there’s lots of uncertainty in kids’ lives at the baseline,” Lachiondo said. “The trickle-down effect is kids absorbing uncertainty and low resiliency.”

Housing insecurity has also stressed families. And then there’s social media. Kids have a hard time seeing past highlight reels and are already somewhat insecure.

“It impacts image and self-esteem quite a bit,” Lachiondo said.

Safety is another factor. Feeling safe at home and at school is essential to kids’ wellbeing. One adolescent patient told Lachiondo that her school recently had two lockdowns because someone suspicious was wandering around. Other adolescents have felt unsafe in their home due to alcoholism or other reasons.

Lachiondo says these conversations with young patients are important, because it helps her understand how various aspects of their life are impacting them.

“So much of what we see physically, there’s a mental component to that, a holistic component, and understanding how all those interplay is really important for all our health,” she said.

In the past, pediatricians just paid attention to physical wellbeing. Lachiondo is happy to see the lens widen to mental wellbeing too. But that shift is not without its roadblocks – the greatest of which is a lack of access to counselors.

“That’s the next big crisis we’re facing,” Lachiondo said.

But a number of stakeholders – from social workers to insurance executives – are working to bridge that gap.

ISU students to provide mental health services to rural students

Idaho State University recently won a $30,000 grant to provide rural K-12 students with telehealth care that will be provided remotely by its social work graduate students.

“Many small, rural schools don’t have counselors or social workers, or they have huge long waiting lists,” Fredi Giesler, the program director for the master in social work program, said.

The partnership with rural schools will help college students get the practice hours they need, and K-12 students the mental healthcare they lack.

The social work students will provide one-on-one assessments, private counseling, group counseling, and/or community and continuing education information – whatever the district wants or needs. The college students will work remotely from Idaho State’s campus, using technology to connect to rural kids.

And the social work students will hone in on whatever specific issues a given community is facing, such as opioid use, substance abuse, suicide, and anxiety, depression, or other mental health concerns.

Nearly 30 school districts have signed up for the program. The program would follow each district’s policy regarding parent involvement and permission.

Giesler hopes the program will help kids attend class, stay motivated, and focus on school. Mental health is connected to academic success, she said.

Giesler attributes the increased need for mental health care to a number of factors, including a younger generation that is less likely to dismiss mental health struggles.

“There’s been a real change in our culture to how we think about mental health and how important it is, but providers have not been able to keep up with that demand,” Giesler said. “Idaho is at the bottom as far as having enough providers to meet the needs for mental health. There just aren’t enough people.”

Social work students have been hired before they’ve even graduated, and there often aren’t enough applicants to fill social work vacancies.

The telehealth partnership should help fill some of the coverage gaps and is slated to begin in earnest next school year.

Insurance companies have also been working to close gaps between patients and providers.

Amid a rise in insurance claims, insurance company adds providers, increases reimbursements, advocates for screenings

Jim Polo is the executive medical director for Regence BlueCross BlueShield of Oregon and also facilitates some projects in Idaho. He said there’s been an increase in mental health-related insurance claims among adolescents and his company is working to add more mental healthcare providers to its networks to help meet those needs.

Polo said that even before the pandemic there was a concerning trend of “kids struggling with feeling sad or hopeless, having suicidal thoughts, and making suicide attempts.” The pandemic worsened things.

“For adolescents, the pandemic disrupted their entire lives. They lost their ability to be involved in social activities with other kids,” he said. “The reality is school is really about their development from a social perspective … it’s about growth, development, and self-identity.”

In addition to adding more providers to its network, the insurance company is also increasing the amount it reimburses for behavioral health services. It’s also matching rural clients with telehealth services to ensure needs are met.

But telehealth counseling isn’t always appropriate for children, who might need play therapy or other such in-person treatments. Another obstacle is that there are fewer providers for adolescents/children than for adults. There’s also higher risk liability for adolescent patients, and some healthcare systems aren’t willing to accept them. Nationally, hospitals are closing down pediatric units.

But the shift toward mental health screenings at doctors’ offices is good news, Polo said.

“Stigma prevents a lot of people from openly seeking services,” he said. “Screening routinely takes away some of that stigma, and helps connect people to providers.”