On the fast-growing outskirts of Idaho Falls, the Bonneville School District struggles to hang onto classified workers — such as bus drivers, custodians and cafeteria staff.

Bonneville competes on the job market with the neighboring Idaho Falls School District — and fast-food restaurants, both of which pay more than Bonneville.

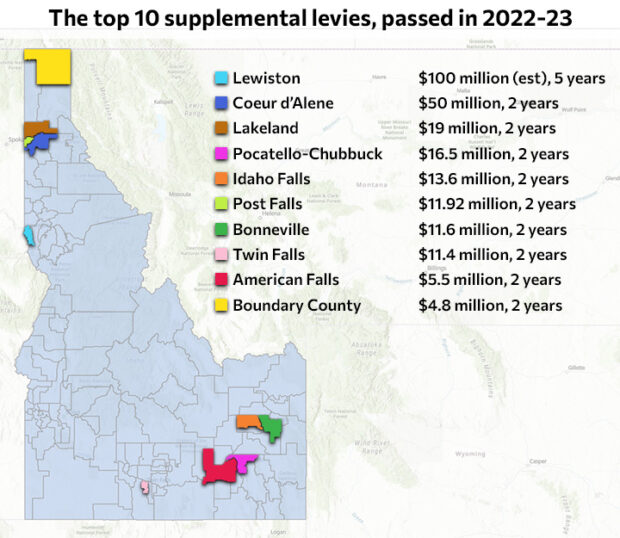

A two-year, $11.6 million supplemental property tax levy, approved in November, should help Bonneville boost its hourly classified wages from $10 to $13. Time will tell if the raises will be enough to bring in applicants.

The hiring challenge is hardly unique to Bonneville. Across Idaho, school districts routinely make similar requests of their voters: money to hire additional staffers, offer a pay raise or beef up benefits. By and large, voters say yes.

In the sagebrush outback of Twin Falls County, near the Nevada state line, the tiny Three Creek School District went to voters in August for money to hire a teaching aide to serve its four kindergarten through eighth-grade students. The two-year, $40,000 levy passed on a 13-3 vote.

Idaho districts continue to depend on supplemental levies to pay for their personnel costs — even after the Legislature has made significant investments in salaries and benefits over the past several years. The reliance on voter-approved levies carries some risk. It means districts are leaning on one- or two-year tax measures to cover their largest perennial expense: people.

Breaking down the dollars

In 2022, the Legislature required districts to include “a detailed description” of spending plans on their supplemental levy ballots. The language went into effect starting with the August elections, affecting Three Creek and three other districts.

The ballot language allows some rudimentary analysis of where districts plan to spend their money.

Idaho Education News analyzed ballot language from 45 school districts, and voter-passed levies that will generate nearly $95.1 million in 2023-24.

There are some caveats.

First, ballot language varies; some districts go into great detail, and others are vague.

Second, there is a lot of overlap. Employee salaries and benefits can cut across several categories. A transportation line item might include bus drivers’ salaries, for example, and a safety line item might cover school resource officers’ salaries. That’s the case in Bonneville: Superintendent Scott Woolstenhulme says about 90% of the money will support staff across the gamut, from administrators and teachers to coaches and clerical staff.

Second, there is a lot of overlap. Employee salaries and benefits can cut across several categories. A transportation line item might include bus drivers’ salaries, for example, and a safety line item might cover school resource officers’ salaries. That’s the case in Bonneville: Superintendent Scott Woolstenhulme says about 90% of the money will support staff across the gamut, from administrators and teachers to coaches and clerical staff.

Here are the rough breakdowns of where the $95.1 million will go. The numbers aren’t all-inclusive — and they represent low-end estimates:

- Salaries and benefits: At least $48.9 million.

- Transportation: At least $7.5 million.

- Extracurriculars: At least $7.3 million.

- School safety: At least $6.9 million.

- Curriculum and supplies: At least $4.3 million.

- Technology: At least $2.4 million.

As schools continue to rely on levies for their personnel costs, Idaho School Boards Association deputy director Quinn Perry is left with mixed feelings.

If a district wants to hire additional teachers to reduce class sizes, that is supplemental spending and a decision that should be left to local voters, she said. But Perry is concerned about other deficiencies in the education budgets: transportation funding that isn’t keeping pace with local needs, extracurricular programs that are often funded only through local levies, and other gaps.

“Are curriculum and supplies supplemental?” she said. “Is technology supplemental?”

The EdNews analysis found some smaller line items that are outliers — and perhaps throwbacks. In Hansen, $13,000 will go toward free developmental preschool: “Many of our parents have difficulty paying for the service,” Superintendent Angie Lakey-Campbell said. In Meadows Valley, a weight room will get a $50,000 upgrade. In Cottonwood, $12,000 will cover janitorial supplies.

There was a time when districts could routinely use supplementals for a small add-on, like a weight room or an athletic field, state superintendent Debbie Critchfield said. Looking at the next round of levies, she said, that is clearly no longer the case.

“It really illustrates the fact that the current way that we fund schools is not keeping up with the modern context of educating a kid,” Critchfield said.

‘It’s always people’

About 500 miles and a time zone removed from Bonneville, Coeur d’Alene’s plans for a supplemental levy are more or less the same. Over two years, the $50 million of voter-approved money will go almost entirely into salaries and benefits.

“It’s always people,” Superintendent Shon Hocker said.

And in districts like Coeur d’Alene, it’s people the state will not pay for.

The district’s share from the state’s general fund is enough to cover about 518 full-time teaching positions, according to State Department of Education data. Coeur d’Alene covers more than 30 teaching positions beyond what the state funds, and has an additional 75 federally funded teachers, Hocker said.

East of Moscow, the rural Genesee district is collecting a much smaller levy: $1.185 million next year. But that levy covers about a third of Genesee’s salary and benefits costs, and helps the district employ seven teachers that the state doesn’t fund, Superintendent Wendy Moore said.

If administrators and school trustees want to add teaching positions and reduce class sizes, they have to find other ways to pay the wages. And it’s happening in school districts all across the state. In 2022-23, the state’s general fund provided enough money to support about 15,300 full-time school district teaching positions, according to State Department of Education data. The districts actually filled more than 16,600 full-time positions — paying for the balance with federal dollars or short-term property tax levies.

In some ways, districts might have even more trouble keeping classified employees — the support staff that keeps a school running. The state’s funding for classified pay doesn’t keep up with what the schools have to dole out to keep their custodians, bus drivers and cafeteria staff on the job, instead of grabbing a readily available and often higher-paying job in the service sector.

“There are many people who are reluctant, or they don’t feel good about, ‘I’m paying more taxes so that you can have more take-home pay,’’ state superintendent Debbie Critchfield said. “Not that we don’t value teachers, but those things are a direct line.”

And again, if districts want to add classified employees, it’s up to them to find the money.

North Idaho’s Potlatch School District is facing a recurring issue — behavioral issues, particularly involving students with disabilities. The district needs classroom paraprofessionals and other classified staff who are skilled at working on behavioral issues, and more of these employees than the state funds, Superintendent Janet Avery said. The district’s one-year, $1.6 million levy helps to fill that gap.

But none of this comes without risk: It is inherently dicey to use short-term property levies to cover ongoing labor costs. And none of this comes without some level of community pushback.

“There are many people who are reluctant, or they don’t feel good about, ‘I’m paying more taxes so that you can have more take-home pay,’’ Critchfield said. “Not that we don’t value teachers, but those things are a direct line.”

‘They knew there was a lot more money coming’

Rep. Wendy Horman says she is surprised that districts continue to lean on levies to pay for personnel, considering the recent legislative history.

In a one-day special session in September, lawmakers approved $330 million in permanent funding for K-12. That $330 million was on the books well before districts had to finalize their plans to run levies in March — the perennial school election day of choice, but one the Legislature eliminated effective in 2024. And even before districts were preparing for March elections, they had a chance to see Gov. Brad Little’s education budget request for 2023-24, which included proposals to earmark $145.6 million of the special session money for teacher salaries and $97.4 million for classified salaries.

When the co-chair of the Legislature’s Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee looks at this record, she doesn’t understand the districts’ push for the levies. “They knew there was a lot more money coming,” said Horman, R-Idaho Falls.

Rep. Julie Yamamoto wasn’t surprised, however.

The levy breakdown squares with what lawmakers heard in her House Education Committee — about the struggle to fill teaching positions, retain experienced teachers in disciplines such as reading, and hang on to classified employees.

“It is a bit of a Whack-A-Mole game,” said Yamamoto, R-Caldwell. “But that’s also what districts are dealing with.”

This series at a glance

Monday: A new law requires transparent levy elections — but the results are mixed

Tuesday: Districts lean on short-term levies to pay for long-term investments — people

Wednesday: All politics is local, and levy elections can be contentious, or routine

Thursday: Lawmakers rewrote the school election calendar. What happens next?