Teachers are ‘coaches,’ classes are ‘workshops’ and students get treated as adults in a school where traditional instruction gets turned on its head.

Boise, Idaho

As high school seniors across the nation crammed for finals last spring, Abella Cathey was in her glory, enjoying a warm spring day as she joined a group of 24 children and their grandparents planting sage, yarrow and milkweed along the banks of the Boise River.

The project was the culmination of a months-long, self-guided inquiry into nature deficit disorder, a phenomenon in which people become disconnected from the natural world.

Cathey, 18, attends One Stone, a student-driven private high school near the heart of downtown Boise. While she was out planting, her classmates were similarly engaged: One threw a free, three-day music festival for pediatric cancer patients and their parents. Others were busy advising a local chef about food waste.

This is the kind of thing that unfolds most days at One Stone — part four-year high school, part educational R&D lab, part design-and-advertising agency — that turns virtually every high school tradition on its head.

Teachers are called “coaches,” and students not only guide the school’s board, but, according to its bylaws, hold two-thirds of board seats and 100% of officers’ positions.

“A lot of people don’t believe that high school students can do meaningful, big things,” said Teresa Poppen, One Stone’s executive director and co-founder. “And I have always believed that they can do meaningful things when empowered and trusted.”

Or, as Cathey put it, “Being treated like an adult is what makes you act like one.”

Each student shows up in the fall expected to manage their own learning, sitting down with advisors to create a personalized learning plan built around their interests and the importance of serving the community.

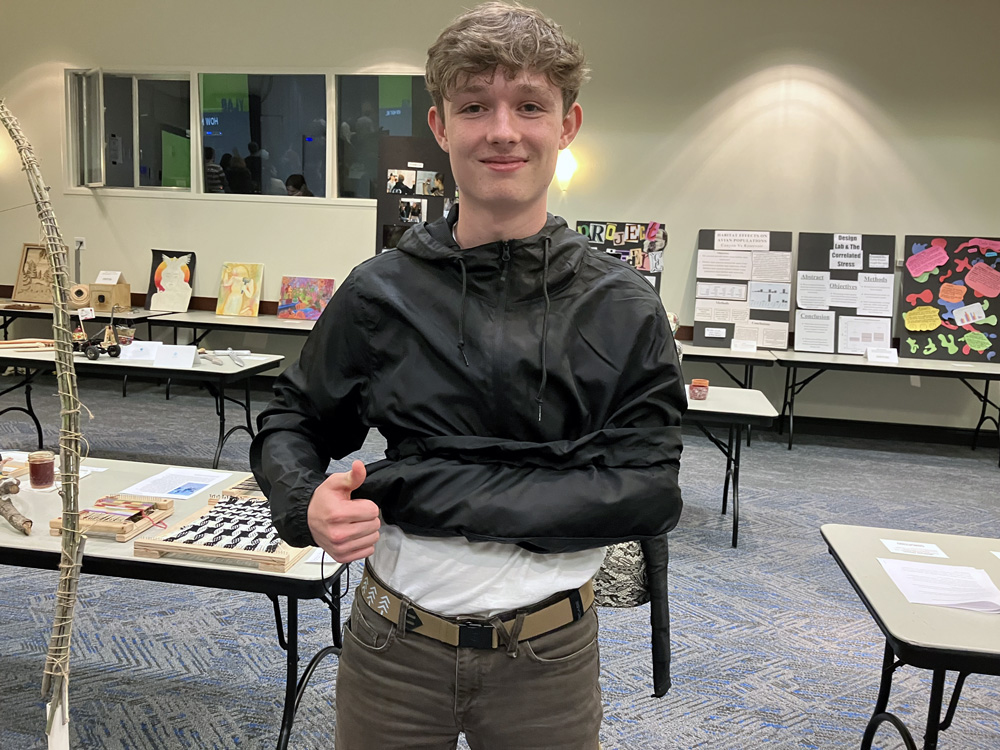

“It’s kind of rare for two people to do the same thing,” said Henry Fears, 17, who has spent much of the past year designing a dual-purpose windbreaker for mountain bikers. In the event they take a spill, it doubles as a sling.

While factual knowledge, here as elsewhere, plays a key role, the school’s four-part “Bold Learning Objectives” — a framework endearingly called the BLOB — puts knowledge in its place, giving it equal footing with creativity and a forward-thinking way of approaching problems that has has become an education buzz-phrase: a growth mindset. The result is a bespoke, four-year education that supporters call a “toolkit for life.”

‘We had no intention of building a school‘

The school may seem like an experimental throwback, but its brand of thinking has been building steam — and converts — for years.

At least part of its model, a complex “growth transcript” that tracks students’ development in several non-traditional ways, could soon be more widely available: Last year, the school secured close to a quarter million dollars in National Science Foundation funding to further develop the idea. It’s testing the waters via licensing agreements with a handful of schools, in hopes that the transcript can provide an ongoing, if small, future revenue stream.

Like most endeavors of its type, One Stone started life as something else entirely. It began in 2008 as a project-based afterschool program for local teens. With its young clientele pushing for more, One Stone’s founders brought groups of 150 high school juniors from across Idaho into a local hockey rink, where they brainstormed what to do next.

“What they came away with is [that] they needed a place to explore their passions and really find out what drives them,” said Celeste Bolin, who directs Lab51, One Stone’s high school program. Essentially, students wondered: Why can’t school be more like One Stone?

“We had no intention of building a school — zero,” said Poppen, the co-founder. “Nor did we really love the idea when kids brought it up.”

But the students made a powerful case that they needed a place and a schedule that allowed them to focus more closely on their interests — no small endeavor for a generation diverted by digital distractions.

“They don’t want to go from class to class, hour to hour to hour,” Poppen said. “When they find something that they want to dive into, they want to be able to dive into it in ways [that] are meaningful.”

The rink sessions also revealed that teens wanted a more purposeful kind of education, one that embraced both community service and their own personal goals.

So, reluctantly, and with a grant from the Boise-based Albertson Family Foundation, the school opened in September 2016 with 32 students.

For its first six years, the non-profit charged no tuition. But with the Albertson grant sunsetting, the student-led board last year voted to enact tuition on a sliding scale — from a maximum of about $16,000 to virtually free for families who can’t afford it. One Stone says families with incomes below $75,000 pay as little as $150 annually.

Mackenzie Link, a senior who chairs the board, said the move, though difficult, “can keep us around for 10, 20, 30 more years.”

Before finalizing the move, Poppen sat down with every One Stone family. Just three opted to leave.

‘The space for uncertainty’

Day-to-day, the school looks nothing like a typical high school. Its one-story building comprises a handful of open-concept rooms, bordered by coaches’ offices and closed-door spaces for cooking, 3-D printing and music production.

The rooms shift quickly from meeting space to arts workshop to performance space. The furniture never seems to stay put.

The school day begins later than virtually any other high school in the nation — 9 a.m. “7:50 (a.m.) is too early for most young brains,” said Bolin. “They are not switched on yet.”

Students rarely attend formal classes — here they’re called “workshops” — instead working alone, with coaches or in small groups, on material that pushes their projects forward. In math, for instance, they rarely follow a prescribed sequence. In order to graduate, they take part in eight “math experiences” keyed to their projects, said Josie Derrick, the school’s “lead math innovator.” While they might not necessarily take a course labeled Algebra I, One Stone’s transcript translates its offerings into traditional courses for colleges.

Students might find themselves, on occasion, in a classroom watching a coach demonstrate math concepts, Derrick said, but it’s rare. Often, it’s students who come to her wanting to learn more about a topic because they need it to advance their project.

“I think a lot of the magic in what we do is creating the space for uncertainty and complexity,” said Michael Reagan, a One Stone coach and Lab 51’s director of design.

But skills aren’t totally left behind. Derrick realized last year that a few students weren’t getting enough math and built out the school’s math workshops.

Nonetheless, a few students seek outside help.

Last spring, after a year at One Stone, sophomore Caden Chorlog enrolled at Boise High School with a dual-enrollment agreement at Treasure Valley Math and Science Center, a nearby public magnet school. But he soon realized he missed One Stone.

They welcomed him back in the fall, along with his dual enrollment at Treasure Valley.

Many would say that’s actually a very One Stone thing to do: Find what works for you and make it happen.

As a result, virtually every student has a different experience. For instance, while many students spend time making music or putting together benefit concerts and other events, others find both refuge and purpose in The Foundry, a workshop that houses woodworking and welding tools, a 3-D printer, a laser engraver and a fearsome CNC router — a massive automated tool that precisely cuts all manner of materials. The size of a giant dining table, it dominates the room.

The Foundry is where Daniel Krafft, who graduated in 2020, spent most of his time. Krafft has since become a One Stone celebrity with a wildly popular YouTube channel that takes viewers through his 3-D printing projects. At last count, Krafft had 2.1 million subscribers and his videos had nearly 148 million views.

Cadence Kirst first dabbled in the space as a way to make handmade wooden swords for roleplaying games. She then moved on to manufacturing painstakingly detailed wooden boards for a strategy board game called Quoridor.

“I’m hoping to be in here ‘til the minute I graduate,” she said one recent afternoon as she prepared a few of her prototypes for the school’s “Disruption Night” expo, held at nearby Boise State University.

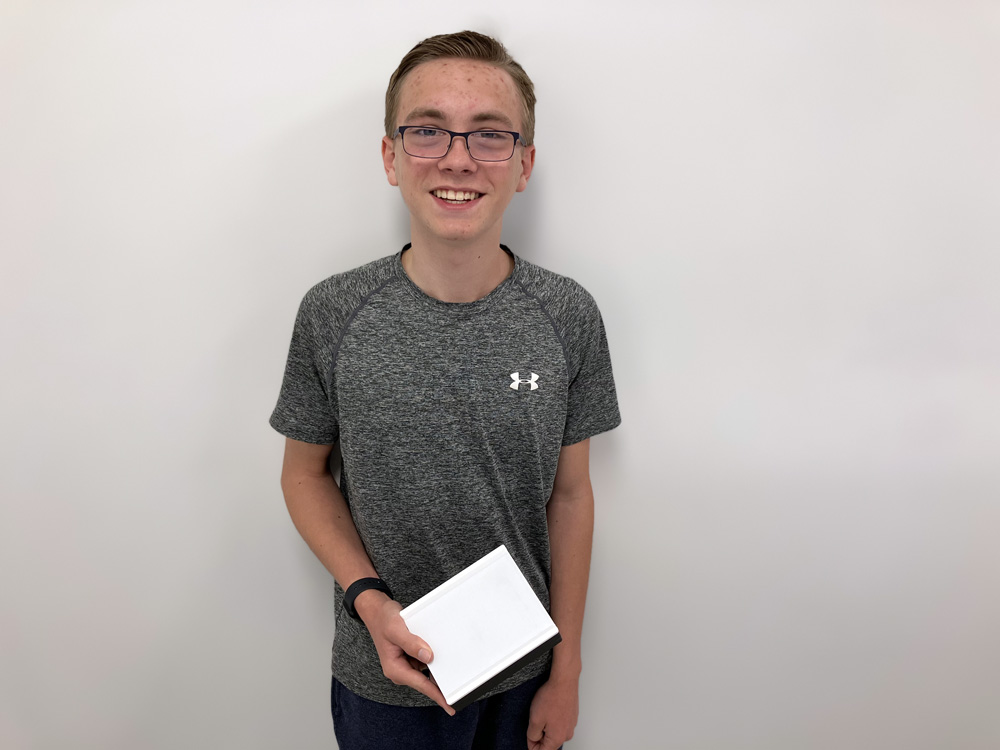

It was there that Fears showed off his prototype windbreaker, developed in a One Stone entrepreneurship program after a biking trip with his father, who broke his clavicle and had to descend a mountain unassisted. And Chorlog, the dual-enrolled student, showed off another invention prototyped in The Foundry: a small, 3-D-printed reusable box for small mail parcels.

A group of students detailed their efforts working with the chef of a local high-end restaurant to reduce food waste, while another talked about developing a manual for kids to learn about distracted driving so they could discuss it with their parents. Tabitha Smith, an official with the Idaho Transportation Department, told the crowd she brought a draft of the manual back to the office and showed it to co-workers, who were “blown away” by the students’ handiwork.

“I have worked in highway safety for about four years now and this is unlike anything we’ve ever seen,” she said. “They picked a whole new audience to market to.”

By this fall, Smith said, Idaho drivers should see a final, co-branded version of the manual “in your DMV, county offices and pediatrician’s offices.”

‘They’re tenacious’

The manual, as well as other materials, come compliments of the school’s Two Birds studio, a professional-grade branding and marketing firm that every One Stone student takes a spin through. And yes, the name is a play on the famous adage about what to do with one stone. Run by a recent alumna and powered by student labor, the firm sells its services to local, regional and national businesses, with proceeds underwriting the school’s budget.

“We build our schedule around experiences,” said Bolin, the Lab51 director. The lab’s name comes from the concept of “51ing” an idea, she said. “We say your first 50 ideas have probably all been thought of as not very creative. We need 51 and beyond.”

To get there, she said, One Stone students are “constantly practicing, talking about what they did, how they grew, what was hard, what they’d like to do — over and over and over again. They’re writing about it, they’re talking about it. They’re telling big groups of people about it and telling small groups of people.”

They’re talking to team members, parents and mentors, she said. “Practice, practice, practice, practice.”

As a result, she said, they begin to see that their experience has value and their endeavors are worth fighting for. “They’re tenacious … They don’t just give up.”

One Stone boasted an 83.8% college acceptance rate this spring and more than $2 million in projected four-year merit scholarships.

Dean Kahler, vice provost for enrollment management at the University of Idaho, said he’s starting to get applications from One Stone students and has enrolled a handful. He’s impressed.

“It is a neat school and they do produce really wonderful students that are problem-solvers and leaders,” he said. “And they’re collaborative with one another.”

‘The next thing to care about’

As she prepared for graduation recently, Link, the board chair, was also working on securing the school’s accreditation with the Northwest Association of Independent Schools. The school’s highest-ranked officer, she can hold forth on nearly any detail: finances, operations, strategic plan. She has also been known to stay late and sweep the floors.

Asked what’s next for her, she laughed and said, “I’ve gotten to the point where I’m really comfortable saying, ‘I don’t know.’”

She just earned a license to be a certified nursing assistant. She also plans to work at a lavender farm this summer. Maybe she’ll go to the University of Idaho in the fall and join a sorority. Eventually, she’d like to work as a midwife or nurse practitioner in developing countries.

But she’s also really interested in construction management. It’s all very exciting, she said, and she’s in no rush to decide. She just wants to find something she can throw herself into completely. “I want the next thing to care about.”

Click here for The 74