Richard Guerrero was nervous. He had just taken the language arts portion of the GED exam again, after multiple attempts. He expressed he felt good about it, but was waiting on his scores.

“Hey Richard,” his instructor said, grinning. “You passed.”

Richard stared at him, a look of wonder on his face. Then, it hit him. He jumped out of his seat. “I passed? I passed!” he exclaimed, pumping his fists in the air with tears in his eyes. “I did it? I did it!” The instructor, also tearful, pulled him into a quick but strong hug and said, “congratulations.”

Guerrero is incarcerated at the Idaho State Correctional Institution (ISCI), a 1,446-bed men’s prison in Boise, one of the 10 state prisons managed by the Idaho Department of Correction (IDOC). He was convicted of witness intimidation and aggravated battery and came to prison without his high school diploma.

For over two years, Guerrero has been working towards getting his GED through the prison education system.

In the beginning, he felt discouraged trying to do school and almost quit. He explained, “I was like, ‘I can’t get this, I’ll never get it.’ But then I started to understand more.” Guerrero attributes his success to the staff working with him in the prison education program. “It’s because of them and everyone here [that I passed]. I’ve had them on my side, they’ve been my fans.”

ISCI’s education staff includes four teachers: two who teach GED subjects (math, science, Language Arts, social studies), one who prepares those in prison to transition after their release and another who teaches financial literacy. Instructors also teach elective classes like horticulture.

Guerrero is on his way to join the almost 1,500 incarcerated people since 2017 who have completed their GED in Idaho’s 10 prisons, with an average pass rate of 84%, which is 6% above the national average.

He also chose to pursue education, as it is not required. About 13% of the 7,110 people incarcerated in Idaho state prisons choose to participate. Once he finishes his GED, Guerrero plans on pursuing other vocational classes, and even college courses.

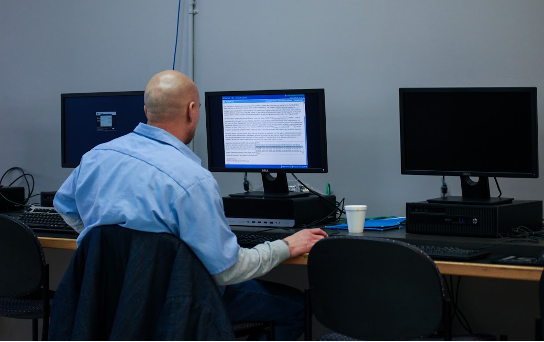

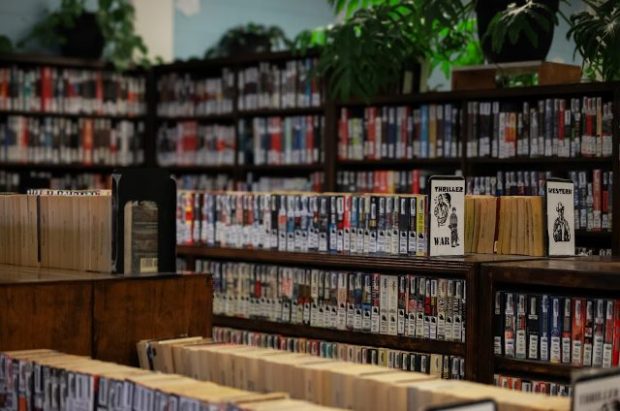

Walking into the educational section of ISCI you’ll run into plants, dozens of them, grown by the horticulture class. You’ll see artwork on the walls created by those in prison. Incarcerated people will be working on computers, using the professional video editing software DaVinci Resolve to create videos for the prison’s TV channel. Some will be working as teaching assistants. You might see someone reading one of the 20,000 books in the prison library or even crocheting a small creature.

The goal of educating prisoners isn’t simply to pass the time. Idaho’s incarcerated residents on average have obtained significantly less education than the general population.

| 2020 | No High School Diploma | High School Diploma |

| Idaho General Population | 8.5% | 91.5% |

| Idaho Incarcerated Resident Population | 33.9% | 66.1% |

Education gives opportunities to formerly incarcerated adults who upon release need to restart their lives, explained Smith. “Every job application says, ‘are you a felon?’ and you have to prove yourself even before you get the interview, that you’re worth the interview.”

That’s why Smith and others work to provide residents with as many opportunities as possible. Computer lab instructor Andrew Strebel has gone above and beyond to do that, winning Idaho CTE’s 2022 Postsecondary Exemplary Program Award for his video production training program. “I’m always looking at creative ways that I can offer these guys new skills, new things to explore, and working with outside partners to develop and bring in resources for these guys.”

Not only does this investment increase adult education levels, but it also decreases recidivism, or the rate of formerly incarcerated people returning back to prison. In Idaho, even small quantities of education make a difference. Those enrolled in education courses through IDOC from 2021 to 2022 averaged a recidivism rate of 14%, while those with less than 20 hours of education averaged a 17% rate.

Federally, studies show the benefits of education in lowering the rate of returning to prison. According to a report done by RAND, a dollar invested in prison-based education saves five dollars on three-year reincarceration costs.

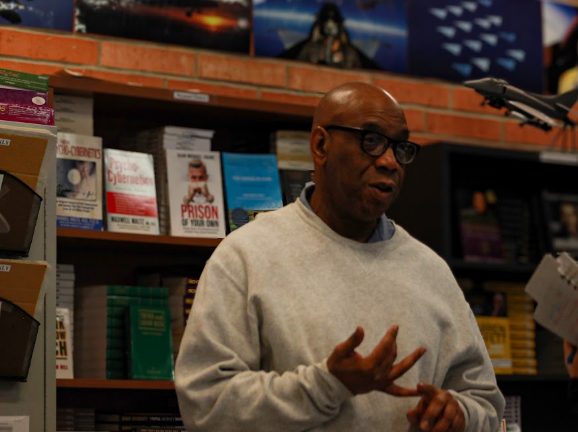

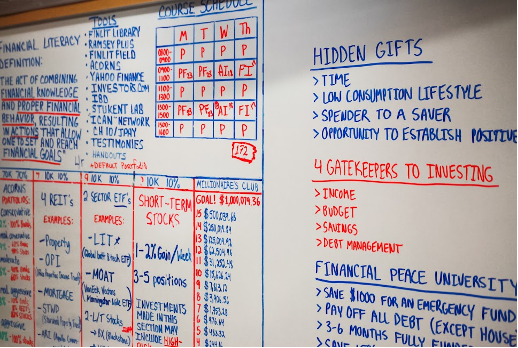

Teaching financial awareness is another way to reduce the number of former offenders returning to prison. ISCI’s financial literacy course was formed after its instructor Jack Dujanovic interviewed hundreds of those in prison realizing, “the same issue kept on coming up time and time again — problems with finances.”

Nick Hearne, who was convicted of drug trafficking and could be eligible for parole in 2034, wants to learn about finances so he can get a job after his release and responsibly manage his earnings. “You can’t get out and change your life if you aren’t financially prepared for it,” he expressed.

Doug Austin was convicted of murder in 1982 and is serving an indeterminate life sentence. But knowing he may never leave prison hasn’t stopped him from wanting to be a life-long learner. He’s most interested in finance.

His first job in prison 40 years ago was working in the kitchens, earning $35 per month. With principles from his prison coursework, he began saving his money until eventually he had enough to make a small investment, which has since grown.

“Learning about how the market works is just eye opening,” he said. “It was a big secret to me and all of the sudden ‘boom!’”

The financial literacy course at ISCI started out with 11 students eight years ago and has grown to three classes and 175 students. Dujanovic was even recently asked to share some of his curriculum with the State Department of Education (SDE) to help with new requirements for financial literacy courses in Idaho’s public schools.

Just down the road at Idaho State Correctional Center (ISCC), another all-male 2,128-bed state prison, vocational classes reign supreme, with waitlists of residents hoping to get into the residential electrical program or carpentry, masonry, drywall and cabinet making courses. Soon they can sign up to be certified in wiring solar panels.

In the construction class, students build a miniature model house in the center of their classroom. The electrical class includes mock crawl spaces for those in prison learning how to wire homes.

In the masonry course, students lay block and brick and for the final project build an arch that must stand after the keystone is pulled. “Anything you would find in a cabinet shop or construction job site, I have, whether it’s tools or materials,” affirmed Michael DiNardo, coordinator of IDOC’s vocational educational programs.

These vocational classes, which generally take about two years to complete, are credited through the National Construction Center for Education (NCCR), meaning each person in prison who receives a certificate gets an NCCR number an employer can look up to verify their skills.

Logan Tysinger, who was convicted of possessing sexually exploitative material of minors, is learning a trade — something he never thought was possible. He didn’t know how to operate a tape measure when he entered prison at age 21. Now, 14 years later, he knows the ins and outs of building a house.

He started by earning his GED, then obtained some of the 15 certificate options at ISCC, including coding, networking, network security and AutoCAD, a program used by architects and construction workers. He hopes to get a job in one of these fields upon finishing his sentence.

Predominantly on his desk, Tysinger keeps a wooden sign, perfect except for a large slash right through the middle of it. He says it “reminds him of his mistake” he made when setting up the cutting machine incorrectly. Similarly, Tysinger comments that other people in prison fear failure and “lack self-confidence,” which keeps them from participating in education courses.

“I think the biggest challenge,” commented computer lab instructor Andrew Strebel, “is changing hearts and minds. It’s showing the residents that they are capable of doing something more.” Education program director for ISCI, Vance Smith, concurred. “The people we work with come from a history of failure…and that becomes an inset part of who they are.”

When it comes to Guerrero, Tysinger, and others like them, Smith explained the impact of small successes. “When they come here, get their GED, they get past it, they see that they can succeed. And it’s crazy to start watching the actual change in people. In a very short period of time [they start] thinking differently or acting differently.”

Education Program Director for IDOC, Ted Oparnico, emphasized the benefits that could come to those in prison with increased funding. Funded mainly from state and federal grants, Oparnico noted that though costs have increased over the years due to inflation and other factors, grant amounts have only increased marginally. Consequently, the number of staff in Idaho state prisons has dropped from 65 in 2011 to 45 this year, a 30% decrease.

Oparnico believes that with increased funding and more staff, the prison education system could continue to expand its course offerings, appealing to the interests of those in prison while also giving them the instructional support they need. He also advocated some form of state-mandated prison education.

Despite funding challenges, Oparnico emphasized the dedication of staff members, “You can just see the passion that the teachers have for what they do.” Of those serving time he added, “That’s what makes it so important to not give up on anybody, because you never know when it’s going to click for them and it’s going to change their life.”