Editor’s Note: This story is part of a series on Idaho’s new investments in career technical education (CTE) programs. Reporter Darren Svan traveled the state to talk with educators who teach the state’s 72,000 CTE students. This months-long series was supported on a grant from the Education Writers Association.

Accountant Christi Kotter, mechanic Chad Crosby and police detective Christopher Martin left secure professions to teach Idaho teens the skills they developed after years in their industries.

These professional experts will make — or break — Idaho’s recent insurgence in technical career training programs in Idaho high schools.

Leaders pushed $60 million additional dollars into CTE and Idaho needs people to leave industry to teach those courses.

“It’s one of the hardest things I’ve ever had to do. You start teaching with a full load of classes and you’re trying to learn the ropes, trying to be the best teacher you can, all while trying to go through college classes at night,” said Kotter, a former accounting manager in Blackfoot.

Superintendent Debbie Critchfield believes building high-quality facilities will help retain current teachers and bring industry converts into education. Her $45 million Idaho Career Ready Students (ICRS) program is fortifying that effort.

“Investing in industry-standard facilities and equipment is critical,” Critchfield said, so much of the millions will incentivize districts to create programs, purchase equipment, and upgrade buildings and classrooms.

Will that be enough to attract industry experts willing to make less and bring a passion for education? Maybe.

Eclectic, highly-skilled educators are the cornerstone

CTE teachers are counted on for more than academics. They have to understand technologically advanced equipment, develop innovative curriculum, teach workplace etiquette and help find employment opportunities.

“If we pull someone from industry, they will take a pay cut. And they have to have that energy and want to make that switch,” said Jason Bair, a Madison High School coordinator and instructor.

Kotter joined Blackfoot High School after 15 years managing an accounting department for a manufacturing company. She took a pay cut to teach business and photography courses.

“I fell in love with the atmosphere and the idea of education,” she said. “I love cutting checks every week, but it doesn’t bring you the same satisfaction as seeing a student figure out how to use a camera for the first time.”

Industry professionals use a three-tiered model to reach certification, requiring extensive industry knowledge, certifications, university coursework or InSpIRE Ready! Training. Many new teachers coming from industry were surprised by the amount of administrative paperwork and certification requirements.

Striking the right balance between certification requirements that ensure the delivery of effective instruction while not creating barriers to attracting teaching candidates is a challenge, Critchfield said.

Teachers typically enter the classroom from industry and are accustomed to working with industry-standard equipment and facilities. “This is where the ICRS program can help, especially for smaller, rural districts who may not have the ability to bond for this type of investment,” Critchfield said.

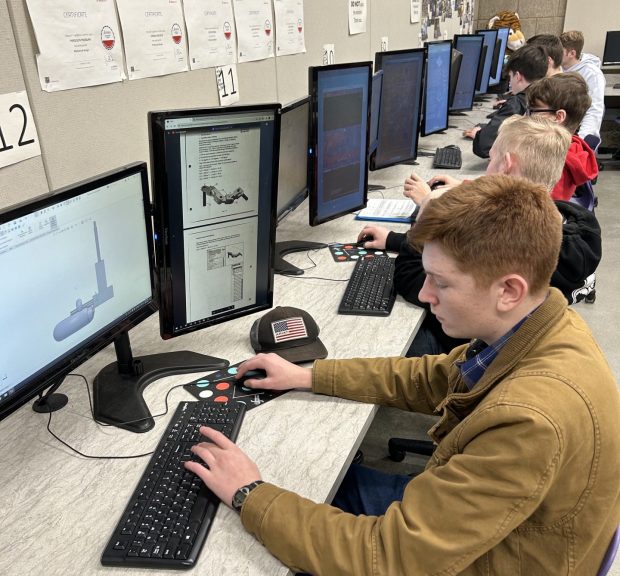

Across the state, CTE teachers are using real-world experience and industry-connected equipment to engage students in classrooms, shops and labs.

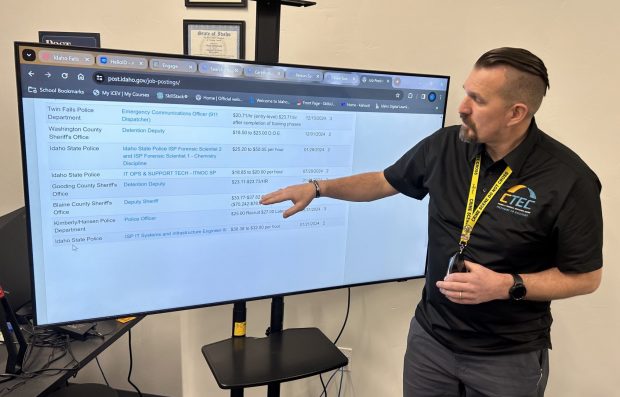

“I like to see the excitement that the students have for learning a new skill set, because every time they do, they’re gaining an understanding of what it’s like to do this profession,” said Martin, a highly-trained retired Rigby Police Department detective.

Martin is a second-year law enforcement teacher at the Career and Technical Education Center in Idaho Falls. His face lights up when discussing the equipment — an inert ballistic vest or handcuffs — and tactics introduced in his classroom. Students will actually issue parking tickets during their morning patrol of the complex.

Eighteen students graduated in his 2023 cohort — nine went directly into criminal justice and nine are exploring career options while attending college.

“They get really excited about doing a lot of hands-on activities,” Martin said.

Morgan Gasca is back where he started. A graduate of Blackfoot High School, he earned a two-year degree from the Universal Technical Institute, worked in the industry and is now in his first year as an automotive teacher. He’s currently carrying a limited specialist license and has three years to get fully certified.

“I’ve always enjoyed helping other people,” Gasca said.

Chad Crosby brings both mechanic experience and a 24-year military career to the job. His program at the DeAtley Career Technical Center in Lewiston has 136 students, is a three-year pathway and culminates with an internship.

Tangible skills like diagnostics or doing light maintenance are part of the curriculum. But so are discipline and workplace expectations. Business owners need to have an employee they can count on — show up to work on time and be committed.

“We know that we need to instill that in our young people,” Crosby said. “They’re looking at somebody who has a lot of life experience.”

In Madison’s “ag building,” Bair’s three-person team of teachers is multifaceted. One teaches building construction, woodworking, large engines, rangeland science class and forestry; while another handles greenhouse plant science, floral design, ag leadership and animal science; someone else tackles agriculture mechanics, welding and fabrication, ecology for fish and wildlife, and aquaculture.

About half the student body of 1,400 students take one or more classes with Bair and his colleagues. “My classes are just packed,” he said.

While Bair and his colleagues prepare young people in Rexburg for agriculture-related careers, Terri Vernado is preparing Lewiston students for something altogether different. A serious-looking group of teenagers listened intently to Vernado, who holds a doctoral degree in technology education and years of industrial engineering experience.

Vernado said, “Next door they are preparing for construction careers but here we’re preparing for the high-tech industry.” She teaches robotics technology, engineering, manufacturing and technological design.

Vernado is a 37-year veteran and will be hard to replace once she decides to retire. In the past eight years, she and the district pulled together enough resources to supply her engineering lab with $500,000 worth of equipment. There is a laser centering printer, programmable logic controls, automation robots, 3D industrial printers and a robot arena.

“The pathway here is very rigorous. We study all four main branches of engineering, so they get problem-solving activities that challenge them to do research, find solutions, actually prototype the solutions, test and analyze, and then communicate their solutions,” she explained.

Fifty percent of her engineering graduates attend post-secondary institutions, 25% go to community or technical college and 25% go directly to work or enlist in the military. One of her recent students is joining the Navy’s nuclear engineering program.

“Engineering means so many different things. Find your passion and pursue it and there’s a place for you,” Vernado said.

Data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report. EdNews photographs by reporter Darren Svan.