Idaho’s graduation requirements may be changing for the first time in over a decade.

Education and workforce landscapes have evolved in that time, and state officials are evaluating whether the path to graduation should be updated to better ensure students are prepared for life after high school — whether that means college, an immediate career, the military, an apprenticeship or otherwise.

State superintendent Debbie Critchfield, who has prioritized career technical education, has been talking with Idahoans about “the value of a high school diploma and how to connect that to the real world.”

“It became clear that there was a need to align student achievement with what Idaho employers are expecting of graduates,” Idaho Department of Education officials said in a written statement.

IDE staff have come up with a slate of possible changes to the existing graduation requirements — which call for a minimum number and type of credits, as well as a senior project — and are sharing them with school leaders and staff at a host of statewide meetings. The first two were held in Southeast Idaho on Tuesday.

The proposed changes include:

-

- Revamping the required senior project so it’s more meaningful to students and focuses on exploring a potential future career. The project would emphasize experiences (like job shadowing or interviewing a career professional) and reflection, and would be called the “Future Readiness Project.”

- Ensuring every student graduates with “currency” for their futures, whether that’s taking a college entrance exam like the SAT, earning a career licensure (like a certified nursing assistant certificate), or taking the ASVAB, a military aptitude test. This is meant to prepare students for the future they envision, whether that’s college, an immediate career, the military, or an apprenticeship.

- A guide to taking electives that support students’ future plans, or a pathway. These guides are intended to help students select coursework that aligns with their goals. They are recommended, but not required, paths. Here’s a draft example of what that could look like (schools would customize the pathways to match their offerings).

Staffing and budget constraints could impact schools’ ability to implement the changes, district leaders say

At a Pocatello meeting Tuesday, more than 40 school leaders were present (either online or in-person), and some were skeptical. The proposed changes —while exciting — could be difficult to implement due to funding and staffing constraints, multiple attendees from rural and urban school districts pointed out.

Greg Wilson, Critchfield’s chief of staff, said IDE would work to support districts in implementing any changes to the graduation requirements, and that they “can’t be an unfunded mandate.”

Another sticking point: CTE teachers can be difficult to find, often because they have professional experience but lack the specific teacher training or certification. Plus, school leaders operating on tight budgets often need to prioritize hiring teachers in required core subjects, like math and English.

On top of that, CTE classes tend to have lower student-to-teacher ratios: “You can’t put 30 kids in a welding class with one teacher safely,” said Sue Pettit, the director of secondary education for the Pocatello/Chubbuck School District. An English class, on the other hand, can hold 30 students.

In other words, smaller class sizes require more teachers, and that impacts the bottom line.

“If we could get some funding for CTE teachers, that would be fantastic,” Pettit said.

Jane Ward, superintendent at Aberdeen School District, said her rural district has the same problems, and many others in the state do, too. She pushed for more flexibility with teacher certifications.

State officials seek feedback via meetings and a survey

That’s the kind of feedback state officials are seeking at these events, which will be held across the state throughout this month. They are also gathering feedback via a survey — which is geared toward school staff, but open to the public.

Public meetings / survey on potential changes to state graduation requirements

June 19, Lewiston

- Where: DeAtley Career Technical Education Center, 3125 Cecil Andrus Way

- When: 1:30 – 4:30 p.m.

- How: Attend in person or join virtually (learn how by registering here).

June 20, Sandpoint

- Where: Sandpoint High, Room S4, 410 South Division

- When: 8:30 – 11:30 a.m.

- How: Attend in person or join virtually (learn how by registering here).

June 26, Nampa

- Where: Columbia High School, 301 S. Happy Valley Rd.

- When: 9 a.m. – 12 p.m.

- How: Attend in person or join virtually (learn how by registering here).

Survey

- You can take the survey, which will be open through June, here. For a preview of the questions it includes, go here.

*The first two meetings took place on June 11 in Idaho Falls and Pocatello

Changes would likely first apply to the class of 2028 or ’29

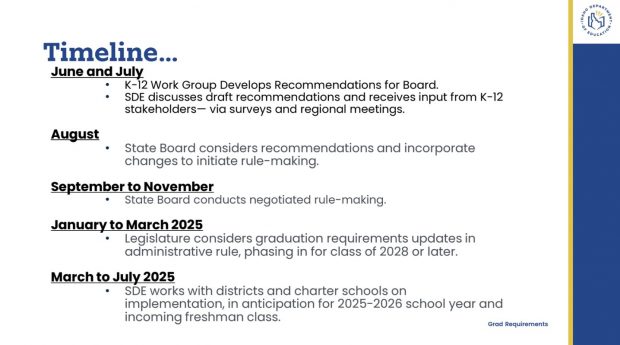

The meetings and survey are the first steps in a yearlong process that will include seeking approval from the State Board of Education and the legislature. If approved, the changes would likely first apply to the class of 2028 or 2029, and could begin being phased in as early as the 2025-26 school year.

In Idaho, graduation rates have stagnated and continually fallen short of state goals. Since state graduation goals have been in place, they have never been met.

In 2023, for example, about 81% of high school students graduated on time, as compared to the state goal of about 95%.

Last year’s graduation rate was a slight increase over past years. Still, rates have hovered between about 79% and 81% since 2015 — except for an uptick to 82% in 2020, when certain graduation requirements were waived due to the pandemic.

Further reading: Most of Idaho’s high school graduates aren’t going on to college — at least not immediately. Our four-part series unveils what they’re doing instead.