State education leaders recently lowered a significant set of long-term academic achievement goals that students have consistently failed to meet.

The scaled-back goals are meant to be “ambitious yet achievable” and to close or narrow persistent academic achievement gaps, according to the state’s consolidated plan.

Already, the new benchmarks are proving to be achievable: For the first time this spring, Idaho students exceeded state goals for math and English proficiency.

Yet, the goals are not necessarily an easy target. They call for slow, steady progress over the next seven years in academic areas where student progress has been stagnant or up and down. And they establish higher expectations for vulnerable student groups, who are expected to demonstrate more growth than their peers.

About the new statewide education goals

The new goals pertain to graduation rates, math and English language arts proficiency levels on the Idaho Standards Achievement Test, and English learners’ progress toward language proficiency. The goals are federally required and are tied to federal dollars.

There are three stated hopes for the new goals:

- That they will be achievable … This has been proven; students have already met and exceeded the first batch of ISAT goals.

- … but also ambitious. While the new goals are lower, goal writers determined they were still appropriately ambitious by taking a look at what would’ve happened if there had been similar goals in place historically. They found that the goals would have sometimes, but not always, been met. Here’s an example:

- That they would help narrow academic achievement gaps. Goal writers cited “longstanding challenges of closing achievement gaps” in their rationale for the new goals.

The process behind the goals:

- Development: Officials from the State Board of Education, the Idaho Department of Education, and the Accountability Oversight Committee collaborated on the goals.

- Focus group feedback: Four online focus groups that were attended by more than 130 people provided feedback, which was incorporated.

- Public comment: Then, members of the public were invited to comment.

- State approval: The State Board approved the goals in June.

- Federal approval: To become official, the goals must be approved by the U.S. Department of Education, a process that will take months. But Alison Henken, the State Board’s K-12 accountability and projects program manager, said it is highly likely that they will be approved.

State superintendent Debbie Critchfield said she is pairing the goal changes with support to help educators and students meet the new expectations — whether that’s teacher training or interventions tailored to student needs. Critchfield is also calling on education leaders to reimagine Idaho’s K-12 education system to ensure that it is relevant for all students and prepares them for a rapidly changing world.

The goal overhaul — delayed by two years because of the pandemic — marks the first time the federally mandated benchmarks have been updated since 2017.

Graduation rates: Critchfield hopes a focus on careers, instead of just college, will keep students in school

Idaho has one of the lowest four-year graduation rates in the nation.

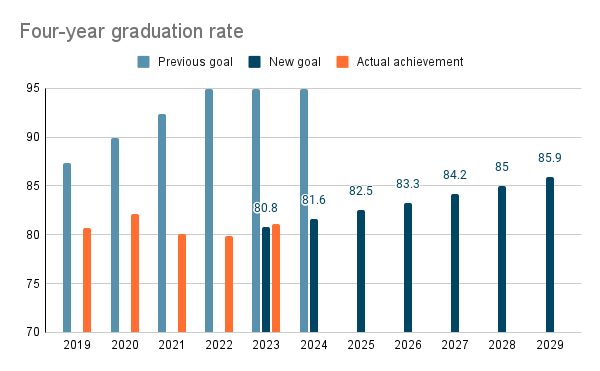

That relatively low rate has remained stagnant over time; about 80% of students graduated on time in 2017, as compared to 81% in 2023. Those rates have perennially fallen far short of state goals that culminated at a lofty 95%.

The new expectations have been tamped down considerably, with sights set on a graduation rate of 86% in 2029.

Still, moving the needle beyond the 80-81% sticking point would be progress.

To get there, Critchfield is calling on educators to make class more relevant for students who aren’t interested in pursuing a four-year college degree. A big part of that is embracing and expanding career-technical education programs and certifications for industry-aligned skills.

“Many of our students who leave high school do so because they haven’t seen the benefit of what they’re doing to what they want to do,” Critchfield said. “If it’s all about the college experience, we’re missing half of our kids.”

And it’s time to think outside the box when it comes to education. “We need to be transitioning more to experiences and practical uses of knowledge, not just sitting in a classroom,” Critchfield said.

Especially for juniors and seniors, high school should be “less about the seat time” and should incorporate more learning that takes place outside of the classroom, like in potential workplaces as part of an internship or apprenticeship.

Proposed changes to graduation requirements reflect Critchfield’s vision, and would allow for a more career-focused senior project. They also reflect the rapidly changing world that awaits students after high school, with a newly required digital literacy course.

“The needs of the modern classroom are different now, therefore our system needs to move more quickly to adjust to that,” Critchfield said.

ISAT math: Less than half of test takers at grade level — that’s a long-term goal.

Idaho’s new math goals set an expectation that about 48% of test takers will demonstrate grade-level proficiency or higher by 2030.

While that would be an improvement from the most recent math exam results, fewer than half of students would meet the goal.

In an interview with EdNews, Critchfield acknowledged the need to boost math proficiency. There already are a few things in the works, like regional math coaches who help support teachers.

But there’s also a need to better train teachers in their university-level preparatory programs, Critchfield said, with a focus on “removing some of the baggage that a lot of our elementary teachers have about their own math skills and not making it so frightening to teach.”

ISAT English Language Arts: Aiming for 59% at or above grade level — keying in on most important standards will help

The new English Language Arts goals call for about 59% of students to reach grade level by 2030.

Critchfield said the most effective way to boost ISAT scores over the years is to ensure that all students statewide are learning the same core skills. Because there are so many standards — which guide what students should know by the end of a school year — teachers don’t always have time to address them all.

That can lead to spotty knowledge sets across the state, with students learning different standards in different places. Identifying the most essential standards that everyone must get through will allow for students and teachers to be on the same page, regardless of where they live. That project is already underway.

“I believe that that important and significant change is going to drive a lot of the achievement,” Critchfield said. “Then we have some confidence that regardless of where a student got their learning, every student is going to know the fundamental facts.”

English language learners: Progress goals are ‘very ambitious’

The new goals for English language learners are the most aggressive.

These goals center on how many language learners are making adequate progress toward English proficiency, and call for a 20 percentage point increase over seven years.

Goal-writers felt comfortable pushing for what they called “very ambitious” benchmarks for a few reasons, according to Alison Henken, the State Board’s K-12 accountability and projects program manager.

First, improvements to the English language proficiency test have made it more adept at measuring student progress. Second, there are now more supports in place for English language learners.

“We have seen some really impressive improvements in the last year,” Henken said.

With beginning English language learners now exempted from the state’s reading exam, the language proficiency exam and goals are a way to ensure those students aren’t slipping through the cracks.

Plus, the language proficiency exam is more appropriate for these students, Henken said, because it’s designed with them in mind — as compared to the state reading test, which is designed with native English speakers in mind.

Closing academic divides will take tailored approaches

Under the new goals, at-risk student groups will be expected to make more academic progress than their peers in a seven-year timeframe.

While those student groups may have improved and progressed academically over the years, “what we haven’t seen is a narrowing of the gap, I think that’s one of the focuses that we have to have,” Critchfield said.

New goals have gap closure in mind

On the math and ELA portions of the ISAT, Idaho students are expected to make improvements of seven percentage points over seven years. But student groups who tend to achieve lower scores on the ISAT are expected to make gains of as much as 10 percentage points in that same time frame.

Below, we compare goals for all students to two such student groups: those with disabilities and Native American students. On the math goals, for example, all students are expected to improve by six percentage points in seven years. But those with disabilities and Native American students are expected to improve by at least eight percentage points.

Part of the solution is providing teacher training. Last year, Critchfield said 600 teachers statewide were trained to implement the science of reading, which she called “the most powerful intervention for students that are in that red area of the (state reading exam).”

That’s an approach that will help all students, but Critchfield said closing gaps is “going to look different for each of those groups.”

For example, she said she’s met with leaders from Idaho’s five federally recognized tribes and has heard that there needs to be more culturally relevant content for Native American students.

The state is in the process of hiring a new Indian education director, who Critchfield said will take on the task of identifying and making available content that is more culturally relevant.

Closing academic divides: Gaps between Native American students and their peers are about cultural disconnect, not a lack of knowledge

Iris Chimburas is skeptical about whether the new state goals will result in narrowing academic achievement gaps between Native American students and their peers.

State leaders don’t really understand why that gap exists in the first place, said Chimburas, the director for the Lapwai School District’s Indian education program, so they’re unable to address it.

She said there’s a number of reasons for the achievement gap, including the way standardized tests are written.

“The ISAT wasn’t created for Native American students,” she said. “There’s a definite cultural disconnect that leads to a misunderstanding of the questions.”

For example, in Lapwai, street names are written in Nez Perce. So if a street name on the test is “Washington,” Native American students might be confused about whether that is identifying a person, place or street.

That’s another key reason for achievement gaps: Native American students are English language learners and need to be recognized and treated as such, Chimburas said.

On top of that, “historical intergenerational trauma” continues to impact students. “People want to erase it like it was a long time ago,” Chimburas said. But “it’s here today … It affects learning, it affects motivation, it affects trust in the education system. It affects everything.”

Chimburas sits on the state committee that developed the goals, and said her peers listened to her feedback, which she appreciated. And she appreciates Critchfield’s focus on providing more culturally relevant curriculum, but said that’s already in place at her school district.

But she tires of giving recommendations on committees, and not seeing action follow.

“Something needs to change,” she said. “It’s not that our students are underachieving … you’re assessing them wrong.”

Closing academic divides: For students with disabilities, learning alongside non-disabled peers is essential

Julian Duffey, the special education director for the Jefferson School District in Rigby, said he thinks the gap closure goals are doable for students with disabilities statewide.

Duffey is also on the state committee that created the new goals and said that benchmarks are important, but what’s most important is that “you have to do different things to try to reach the goal.”

For the special education population, narrowing those gaps will take a concerted effort to ensure students with disabilities are educated among their general education peers as much as possible.

And it’s also critical that teachers don’t “slow down” education for students with disabilities, and instead provide support to help students keep up with learning.

“It requires a lot of effort, a lot of creativity, and a lot of trust and communication with the parent,” Duffey said.