Coming tomorrow: Special education departments face more parent complaints, staff shortages and not enough funds

Shannon Sutorius still keeps an inches-thick pile of printed email exchanges, doctor’s notes and meeting records. They’re heavily highlighted, annotated and dog-eared — a paper trail that tells the story of her journey to advocate for her son, Max Sutorius’, public education.

Max, who has a number of diagnoses that include Tourette syndrome and ADHD, is now 20. He earned his high school diploma in December 2022 from a Utah-based online school after leaving Marsh Valley High — where he and his mother were in a yearslong battle to secure appropriate accommodations for him to learn. Eventually, unsatisfied and disillusioned, Max finished his education at home online.

Shannon is still haunted by the way she says Idaho’s education system failed her child, even with her son’s K-12 days in the rearview.

“It’s one of the most traumatic things I’ve ever gone through,” she said.

A state investigation completed in February 2023 found that many of Shannon’s allegations were true —the Marsh Valley School District did not meet its federal obligation to provide Max with a free and appropriate public education.

Because of “a lack of training and oversight, these errors had gone undetected for some time,” Gary Tucker, the superintendent of Marsh Valley School District, told EdNews in March. “We recognize that we had some holes in our procedures and have worked diligently to bring our special education program into compliance.”

In a Thursday email to EdNews, Tucker pointed out that “while patrons are able to speak freely about their perspectives, school districts are generally very restricted on what can be said regarding the other side of the story. As we all know, there are always two sides, and sometimes they can be very different.”

In Idaho, stories like Max’s are not unusual.

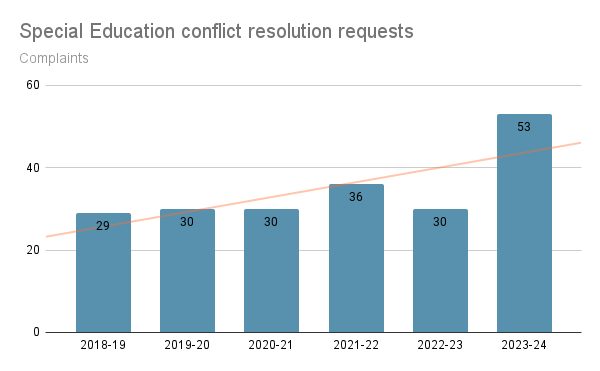

Parents of students with disabilities are increasingly having similar issues, and frustrations are mounting. Last school year, the number of statewide complaints and grievances were the highest they’ve been in the past six years.

Some reached the point of school districts being formally investigated, illuminating patterns of federal special education violations at charter schools and some school districts, including Garden Valley and Oneida County.

The complaints have all had something in common: Parents feeling ignored and in the dark.

In a seeming response, State Superintendent Debbie Critchfield held listening sessions for parents last summer to find out “how our state, districts, and charters could better support their child and lessen the fear of navigating the special education system.” Parents said they wanted two things: knowledge of how to advocate for their children, and support from “an involved educational community.”

The Idaho Department of Education has since created a webpage and guides to help families and is reinforcing that parents “are the final say in their child’s education.”

“The goal of these guides is to provide some clarity for parents and guardians when it comes to navigating the world of Special Education,” Scott Graf, the communication director for the Idaho Department of Education, wrote in an email.

Shannon and parents like her are providing their own version of assistance to families with children in special education.

Shannon has become a go-to source for Marsh Valley families, who she says reach out to her often. She offers advice, guidance and resources, all of which she found the hard way — from scouring the internet and online community forums, reading books and hiring a lawyer to explain federal special education law and state legal processes.

“I felt so abandoned, so alone,” Shannon said. “There was nobody for me to turn to. I tried in every direction … That’s why I’m fighting now.”

Parents of children with disabilities are increasingly finding community in online spaces as well, via social media groups where they can connect, share frustrations and brainstorm solutions.

But advocating for children with disabilities can pit parents against school leaders and carry heavy costs — including financial, social, and emotional. Navigating the system becomes a maze that can take years to wayfind, and some families feel they never come out on the other side.

Some special education experts are also stepping up to help, and say the state’s support systems for schools don’t go far enough.

Frustrated parents on the rise: Calls for the state to step in increased at all levels last school year

Last school year, parents formally flagging issues with school districts’ and charter schools’ special education services reached a six-year high.

When a parent has concerns about special education services at a school, there are a number of steps they can take. The first steps are informal and low-stakes: contacting a teacher, then the principal, then the special education director.

If a parent is unsatisfied with the responses, it can escalate to more serious and formal procedures — which can include facilitations, mediations, state complaints, and due process hearings. The latter two are more contentious and confrontational, and generally arise out of unresolved frustrations.

And there are times when parents say the state processes fail and do not result in meaningful change for their child. So they reach a step higher, and file complaints with the federal Office of Civil Rights.

Currently, there are 20 such ongoing cases alleging discrimination towards students with disabilities in Idaho schools. That’s more than half of the 39 discrimination complaints filed with the OCR against Idaho schools.

At the state level, parent requests for state intervention in local special education programs is at a six-year high.

Facilitations

A facilitator can be requested to be a neutral party at a meeting for an Individualized Education Program (IEP), which is an annual written record that describes a students’ special education needs and how they will be met. A facilitator might be called for if there are disagreements about a student’s IEP among team members. Last school year, there were 187 requests for this — a six-year high.

Complaints

A complaint can be filed by anyone who alleges a violation of the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, but they must file the complaint within a year of the alleged violation. State investigators then determine whether a school district was out of compliance. If so, they prescribe resolution measures, such as required staff training, IEP meetings, updated IEP plans, and/or providing student services that were previously denied. Last school year, the number of complaints jumped to 53 — a notable increase compared to the previous five years.

Due process hearings

Those concerned about whether a student got a free appropriate public education, and/or about the special education processes involved, can request a hearing if it’s within two years of the alleged problem. This step can lead to a formal court-like process — that includes witnesses, testimonies and cross examination — and where the outcome is determined by a hearing officer. According to the Idaho Department of Education, “due process is considered the most adversarial, least collaborative dispute resolution option, and may damage the working relationship between educators and families.”

Mediations

Mediation involves a neutral third party who can help conflicted parties reach a resolution. Last school year, 28 of these were requested — another six-year high.

More resources: Check out the state webpage on dispute resolution, and this helpful chart that distinguishes the four processes.

Special education experts, critical of state programs, aim to shore up training gaps

Julian Duffey, a special education director for the Jefferson County School District, said that part of the reason there’s been an uptick in complaints is that there’s a “vacuum of knowledge” about special education at school districts.

It’s a problem he’s been working to address for years.

Four years ago Duffey and Lyndon Nguyen, a former special education staff member at the IDE, started their own business called Balance Point, a for-profit consulting firm that trains school districts in special education.

But the Idaho Department of Education has been insisting that school districts use state-run training called SESTA instead of seeking help from outside contractors like Duffey and Nguyen.

The state both trains school districts on special education and reprimands them when they fail to meet requirements. In other words, the hand that helps schools also punishes them.

“It’s created a system where the IDE is “judge, jury and executioner,” Duffey said.

Also, districts are “scared” to go to the IDE for help with their special education services, because they worry they’ll get themselves in trouble, Nguyen said.

And now, school districts are disincentivized from turning to Balance Point instead.

“With the gatekeeping there’s no way to help,” Duffey said.

But Graf said the IDE has not heard similar concerns from others. And the training SESTA provides when a district is out of compliance with federal law is tailored “to a district’s needs, making it a logical and meaningful part of the return to compliance.” And he said districts are welcome to “hire consultants as they wish, and we encourage them to use the combination of resources they consider most worthwhile.”

Another issue: Duffey said SESTA trainings are too focused on procedures — like whether goals and meeting dates were documented — and not focused enough on fundamentals. The latter might entail whether a district has an appropriate handicap ramp, or provides appropriate changing services for students in wheelchairs, or assesses potential links between absences and disabilities.

“Their training is not useless, but they’re focusing on the wrong areas to prevent parent dissatisfaction,” Duffey said.

But Chynna Hirasaki, the state’s special education director, touted SESTA in an interview with EdNews. “It’s a very robust support system,” she said. “It’s actually often referenced by other states as well.”

Under SESTA, each district has an assigned coordinator who they can go to with questions and resources, and it provides professional development, including what is basically a “boot camp for new special education directors within their first two years,” she said.

Graf said SESTA trainings are in line with federal requirements, and that participant feedback has been “overwhelmingly positive.” And he provided survey results from last school year that generally showed satisfaction with SESTA training.

“Going through the annual goal creating was extremely helpful,” said one anonymous survey participant who took a SESTA training session on the IEP process.

“Authentic discussion. Excellent presenters,” wrote another who took the same course.

Parent-district relationships are essential to reducing complaints

An increase in parent complaints about special education programs is a national trend, according to Kimberli Shaner, the state’s special education dispute resolution coordinator.

Hirasaki said the pandemic is one of many likely contributing factors. Today’s students have “more complex needs” and parents are more involved — they are “increasing their skills and their knowledge” and asking more questions than they did before Covid-19, she said.

Many of the parental complaints have a common thread: parents feel excluded from special education processes, and like they are not being heard by school staff.

While parents have the right to be included when it comes to decisions and discussions about their child’s special education, that doesn’t mean districts must do whatever they ask, Hirasaki said.

“Having the opportunity to meaningfully engage in the process … means you have the opportunity to share input (and) listen,” she said.

To help build bridges between parents and school districts, local school leaders should make themselves “visible and available” and help educate and inform parents about special education programs and processes, Hirasaki said. And parents should know there is a district-level special education director they can turn to before taking their concerns to the state level.

Duffey has already adopted that approach at Jefferson County School District.

“I’m a huge fan of partnering with parents because what it really comes down to is communication and trust, and every parent is really looking to be heard and figure out what’s best for their kiddos,” he said.

Since Duffey started at Jefferson County three years ago, not a single complaint has been filed.

“It’s all due to just partnering with parents and listening,” he said.

The Sutorius’ years-long journey for educational accommodations

Max first enrolled in the Marsh Valley School District in 2019. He had just moved from Utah, where he had an IEP in place that provided him learning accommodations like specialized written and reading instruction and occupational therapy.

An Individualized Education Program (IEP) is an annual written record that describes a students’ special education needs and how they will be met.

Shannon thought when she shared that information with the district, they would use that IEP or develop their own right away.

But it took more than two years, countless emails to the school districts, and a formal complaint to the state before Max was evaluated for special education and given an IEP. Even then, the IEP was “wholly generic,” and not tailored to Max’s needs, according to a state investigation Shannon shared with EdNews.

Pouring so much time into fighting for her child took its toll: “It robbed me of my time from my family, from my business, my peace.”

Max has moved on — he works as a house painter and lives nearby.

But for Shannon, the fight continues as she helps other families in the area. “I had so much pain that I wanted to help other people going through it,” she said. “That’s why I’ve been such a strong advocate and have been so convicted in being a voice, because there’s nobody here for the kids … nobody to defend them.”