A new study from the Brookings Institution finds that parents and children differ massively on how much learning happens in school.

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering national education issues. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

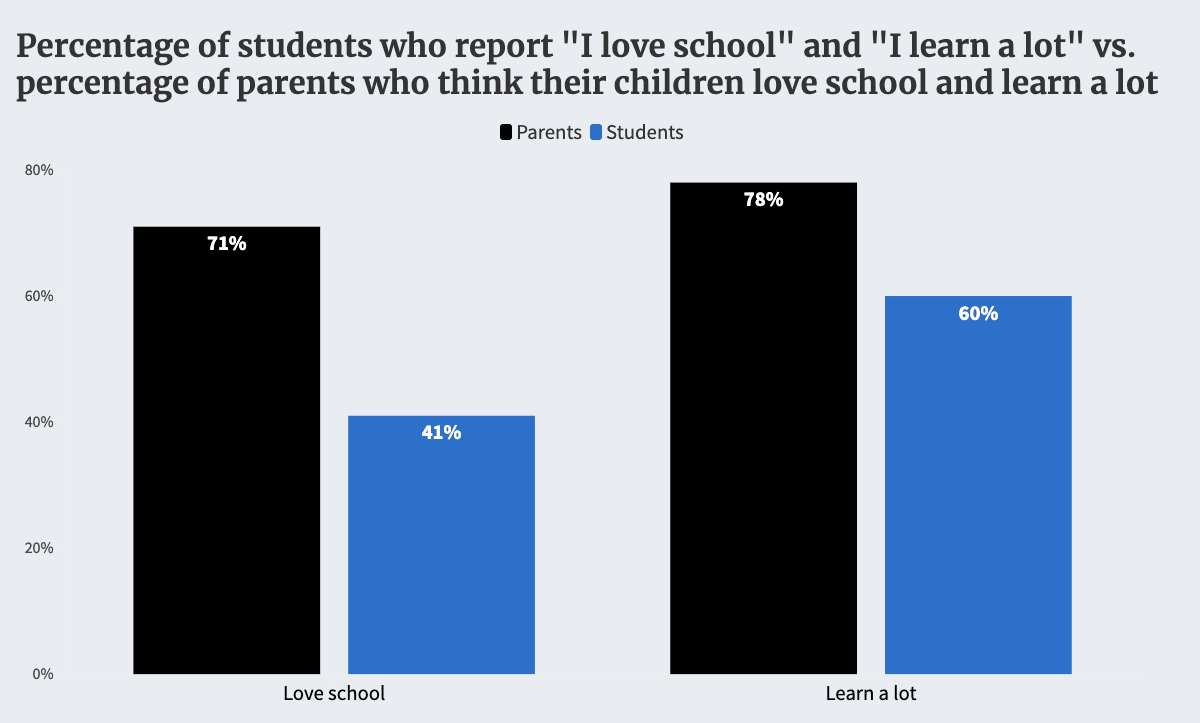

American parents are far more bullish about the quality of learning in schools than their kids, according to a new report from the Brookings Institution. While substantially less than half of all high schoolers say that they believe they’re learning a lot each day, over 70% of parents say they are.

The report, released Monday by the Washington think tank’s Center for Universal Education, shows that parents also appear to overestimate how much students “love” going to school. The divergence in perceptions between adults and children only grows with age, mostly driven by a sizable drop in the numbers of students reporting positive experiences in school after the elementary years.

The figures point to a failure not only to keep students engaged in school, but also to keep families informed about the true state of their children’s learning, said Rebecca Winthrop, the report’s lead author and a Brookings senior fellow. Parents themselves, she added, find it “hard to admit” that K–12 education isn’t offering all that it should.

Data for the report were drawn from the nonprofit Transcend Education, which conducts an ongoing Student Voice Survey querying pupils in public, charter, and private schools around the United States. A nationally representative sample of over 66,000 students from grades 3–12 was asked about their time at school — including their feelings of self-direction, community ties, and the relevance of the material they studied — between 2021 and 2024.

Additionally, Transcend contacted nearly 1,900 parents of school-aged children in 2023 and 2024, generating a trove of responses that has not previously been shared with the public. The findings, along with five years of personal interviews and reporting, have also been compiled into The Disengaged Teen, a book being released by Brookings later this week.

The data highlight a profound degree of academic and social disengagement among teenagers. While students report comparatively high levels of enjoyment and agency at school, less than one-third of middle and high schoolers said they felt that what they learned was relevant to life outside the classroom, that their classmates persevered “when the work gets hard,” or that they had any say over what happened to them during the school day.

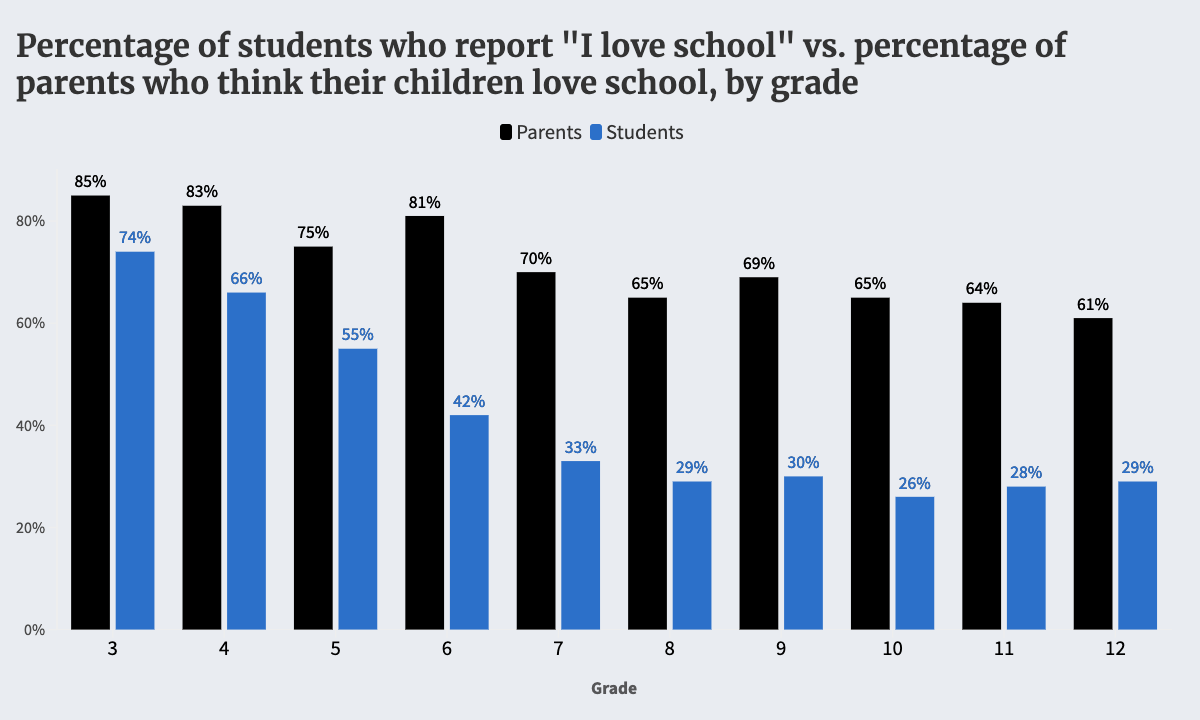

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the jaded responses grew substantially as children aged into adolescence. While 86% of third graders said they learned a great deal in school, just 44% of 12th graders said the same. The portion of students who said they “loved” going to school fell from 74% to 29% over those 10 academic years.

While higher percentages of parents always responded more positively to those questions than children, the gap in perceptions also grows significantly with the passage of time. By their freshman year, just 30% of students say they “loved” attending school; by contrast, nearly 70% of parents said they believed their kids loved their time in the classroom.

Growing alienation from the rituals and relationships of K–12 schools — particularly apparent in elevated rates of chronic absenteeism, which rocketed upwards during the COVID era — ultimately compound in “lost opportunities to form connections with students,” observed Hedy Chang, executive director of the advocacy group Attendance Works.

“Attendance and engagement are inextricably linked,” Chang wrote in an email. “When chronic absence reaches high levels in classrooms, the churn affects all students, making it harder for teachers to teach and students to learn from each other and their instructors.”

Nat Malkus, the deputy director of education policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute, said it would be useful for schools and districts to offer more feedback to parents about the level of student engagement. But it might be a tall order given the existing demands of data dissemination, he wrote in an email.

“Despite quality tests and lots of communication, parent perceptions of their students’ academic progress don’t match what tests are showing,” argued Malkus, who has carefully tracked student engagement and attendance problems over the last half-decade. “So I am skeptical that an additional layer of data collection and communication will be a breakthrough.”

Winthrop said that, atop families’ evident lack of information and COVID-related disruptions to education delivery, older students simply need to receive more independence and options than they are currently getting in conventional schools. Alternative schooling types, such as those that emphasize student choice and even work experience during the school week, could build a healthier sense of self-determination among young adults, she added.