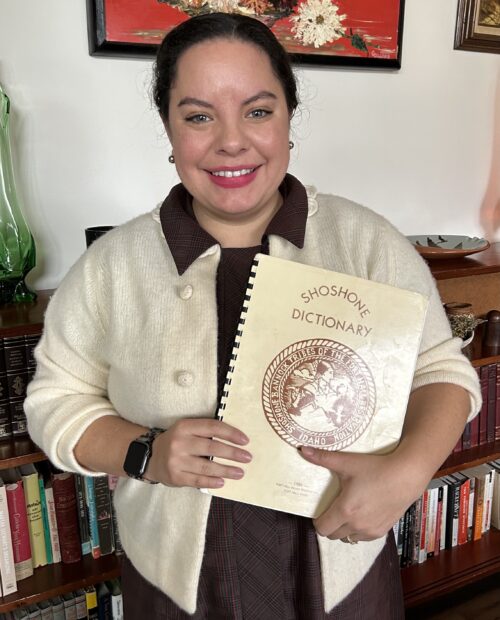

BLACKFOOT – As a child, Bailey Dann would turn to her Shoshoni language dictionary — the one her father gave her — for comfort.

She would read through it in her free time, each translated word a link to her Shoshone-Bannock ancestors and culture.

In middle school, she started her own Shoshoni language club, which consisted of two members — herself and her cousin. They would meet at lunch and make up their own quizzes and flashcards.

“I was always a nerd about languages,” Dann said.

Now an Indian education paraeducator at Blackfoot Heritage Sixth Grade Elementary, Dann teaches the language, one word at a time, to the Native American students she works with. By doing so, she hopes to instill her students with pride and a sense of belonging.

She wants them to know they belong not just in the classroom, but in STEM classes, in honors classes, and on college campuses.

“I’m passionate about transforming the classroom from a place of assimilation and colonization to a realm of possibility and inclusion of STEM and helping students feel like they belong,” she said.

Dann is earning a master’s degree in linguistic anthropology from Idaho State University and was recently featured by Beyond100k, a nonprofit that aims to prepare and retain 150,000 new STEM teachers, especially for schools serving Black, Latinx, and Native American students.

“If we are going to respond to the needs of the century and the opportunities of the economy with equity, we need more STEM teachers in all our communities to inspire all our students from every background and race to flourish in STEM,” Talia Milgrom-Elcott, Beyond100K’s founder and executive director said.

STEM careers are growing and pay the highest salaries, so Milgrom-Elcott wants to make sure all students have equitable access to those opportunities. One way to do that is by making sure that students have teachers who look like them – something Dann didn’t see when she was a young student in Blackfoot.

Having a Shoshone-Bannock teacher would’ve been “monumental,” Dann said.

Now, she is on a mission to be the teacher she needed when she was younger and to reshape the classroom so those who are different are celebrated and included rather than marginalized and cast out.

Generations of trauma in education

At her Blackfoot home one recent evening, Dann laid out photos on her dining room table that depict a troubling throughline in her family history – one of trauma in education.

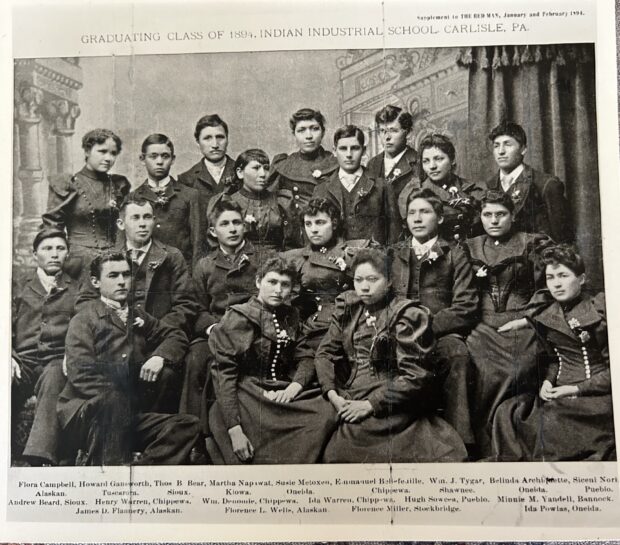

One black-and-white image shows Carlisle Indian Industrial School’s 1894 graduating class. The 19 Native American students posing for the photo are wearing European dress and the men’s hair is cut short. None are smiling.

Among them is Dann’s great-great-great grandmother, Minnie Yandell.

Opened in 1879 in Pennsylvania, the school operated for nearly four decades and became the model for similar boarding schools throughout the country. The children who attended the school lost their cultural identity, their language, and connections to their tribes and family, according to the Carlisle Indian School Project, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the school’s history.

“Students were forced to cut their hair, change their names, stop speaking their Native languages, convert to Christianity, and endure harsh discipline including corporal punishment and solitary confinement,” the website reads.

Disease and harsh conditions were rampant, and some students never made it home. Hundreds died and 186 are still buried at the school site.

“Native peoples who attended boarding schools were traumatized by corporal punishment, isolation, neglect, and abuse,” the website reads. “And we know scientifically that the effects of that abuse can carry on to future generations.”

Yandell was just one of a handful of Dann’s ancestors who attended such boarding schools. One attended a boarding school in California. Another attended the Fort Hall Boarding School, which carries its own legacy of trauma.

Even after boarding schools were shut down, prejudice persisted in modern public schools.

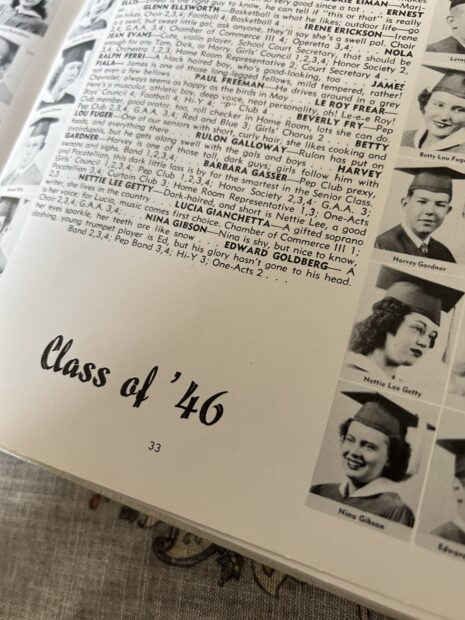

Among the photos on Dann’s table were old yearbooks from Pocatello High School, which include photos of her great-grandmother, Nettie Lee Getty. Getty was one of the few Shoshone-Bannock students there at the time.

The school (and town) are named after Chief Pocatello, who also happens to be one of Dann’s ancestors.

But the pages of the yearbook show that the tribal leader and his culture were not always treated respectfully. For years, the school’s mascot was the “Indians.” It was recently changed to the Thunder.

But in Getty’s time, the mascot lived on.

A 1946 yearbook includes photos and descriptions of all the seniors, including Getty: “Dark-haired, and short is Nettie Lee, a good writer, she lives in the country …” it reads.

The Shoshone-Bannock teen, looking proud and gazing out of the frame in her cap and tassel, shared the pages with crude caricatures of stereotypical Native Americans, including one cartoon image of a Native man being hanged from a Totem pole.

“There are no words,” Dann said of how the images made her feel.

Dann has also had her own firsthand experiences with prejudice in Idaho classrooms.

In grade school, she remembers the few times a year when Native American students specifically would be pulled out of class and checked for lice. She still remembers the shame that came from that, and her grandmother telling Dann she had gone through the same thing.

In third grade, she presented about the salmon life cycle for a science fair. She brought in some cooked fish and a traditional Shoshone-Bannock fishing spear as part of her display.

She still remembers her classmates’ cruel reactions. “Gross! Why would you eat that?” some girls said while holding their noses. “Why wouldn’t you just use a regular fishing pole?”

Dann felt isolated, like she didn’t belong. It would have been a different story if she’d had a teacher who would’ve stood up for her or reframed her project so her peers better understood it.

She can’t change the past, but she can create a better future for others.

Today as a paraeducator in Blackfoot, she sees kids pulling the long hair of Shoshone-Bannock boys – and she tells them to stop.

“I make a difference, even if it’s a little one,” she said.

Reenvisioning the classroom

Dann started her teaching career at Chief Taghee Elementary, a Shoshoni language dual immersion school in Fort Hall. After a few years she switched over to Blackfoot Heritage to work as a paraeducator while completing her master’s degree.

Many of the students she works with are nieces and nephews. When she comes around, they know they need to “act good.” And if they don’t, Dann often knows their family members and makes a quick call home.

At first, the students saw her as a “strange lady,” but have come to know her as a Shoshone-Bannock woman who understands their background and will share bits of the Shoshoni language with them. The students can now say phrases like “hello” or “how are you?” in Shoshoni, which piques other students’ curiosity and starts a dialogue about tribal languages and culture.

“I want to lift up Native American youth through teaching the Shoshoni language so they have the tools to share stories and amplify them as they gain voices,” Dann said.

In her role, Dann acts as a cultural liaison of sorts between Shoshone-Bannock students and teachers who “don’t have that extra understanding of reservation life.” And she knows better than to give up on kids or to see them as a lost cause because they haven’t been attending school or doing their work. Letting kids know she cares about them and that they and their culture belong at the school makes a difference.

“My goal is to support Native students and create a classroom that’s never been seen before in this community,” she said.

She wants to see a classroom where all identities are welcome, where reflexivity is fostered, and where teachers disrupt the power dynamic so students are teaching, too.

And in a country where the Shoshoni language was once illegal in the classroom, she wants to see it celebrated and honored.

“Shoshoni language revitalization is my calling, it’s who I am,” she said.

When the language belongs in the classroom, Shoshone-Bannock students will feel more like they do, too. And Dann wants them to know they belong in other places, too – like in STEM fields, in honors classes, and on college campuses.

Teachers have the power to make students feel like they belong – or don’t

When Dann was a student in the Blackfoot School District where she now teaches, she took a test and was placed into a lower math class. In that class, she looked around and noticed: “this is where the other brown kids are.”

But in her honors classes, she was one of just a few Native students.

“It made me question how come the other kids don’t get these opportunities? How come we are so tracked and separate? And it made me question that,” Dann said.

She would go on to become a first-generation college student, triple majoring at Grinnell College. She attributes her success in higher education to the honors teachers who pushed her, and she knew that the “brown kids” in the lower-level classes didn’t have the same chances she did.

“Those teachers in the math classes didn’t care,” she said. “It made me think a lot about how teachers’ attitudes can have a large impact on students.”

Her experiences are not unique among students of color in STEM classes.

Beyond100K conducted a survey in which 600 students, mostly people of color, shared their experiences in STEM classes. Many recalled being the only student of color in an advanced class, and having teachers question whether they should be in that class.

“When we feel like we belong, we persist and succeed, and when we don’t, it’s really hard,” Milgrom-Elcott said. “When kids felt belonging, it was almost always because a teacher made them feel that way.”

Dann said Native American people have been scientists and mathematicians forever. She pointed to traditional practices like tanning hides that require math and science, and the way the language is constructed – each number tells a story, and sometimes is a math problem in itself.

As an educator today, Dann is constantly asking herself: “How can I transform the classroom into a safe space where they get to be scientists, mathematicians, and engineers and not feel like they don’t belong, because STEM isn’t white.”

Recruiting and retaining more STEM teachers of color is one way to do that, Milgrom-Elcott said – and that’s just what her organization is striving to do.

“There’s so much data about how challenging it is to be what you can’t see,” she said. “All communities are more diverse than our teacher bodies – everyone has work to do.”