Editor’s Note: Idaho is one of the nation’s fastest growing states. There are more trade careers and healthcare opportunities than ever before. And education leaders are beginning to pay attention. With the support of a grant from the Education Writers Association, reporter Darren Svan embarked on a months-long investigation into career technical education programs, industry partnerships, employment trends and accountability. Today’s story looks at what’s happening in Idaho’s CTE landscape.

From state-of-the-art engineering labs to cluttered automotive shops with dismantled diesel engines, Idaho is shifting millions of dollars toward classes that prepare high school students for industry jobs.

Industry leaders are encouraged by the state’s career-focused renaissance, because there was not enough being done to close the gap between industry needs and the labor force graduating from secondary and postsecondary institutions. Idaho’s workforce is increasingly shifting toward skilled trade jobs. Construction, welding, automotive, machining and healthcare expect double-digit growth.

Meanwhile, state and education leaders have grown to accept that most Idaho young adults aren’t interested in higher education. The rate at which Idaho high school graduates continue their education has hovered near 40% for years. To answer this need, the state has begun diverting funds toward preparing high school graduates for the workforce.

“I think they’re all listening,” said Doug Sayer, founder and chief business officer of Premier Technology, a dynamic manufacturing company in Blackfoot.

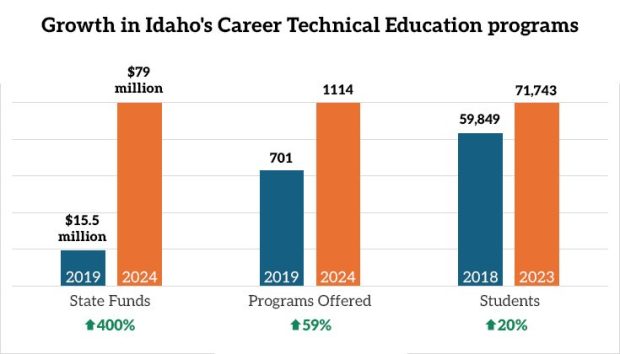

State leaders increased career technical education (CTE) spending by $60 million this school year, a 315% jump over last year. The 2024 increase comes from two sources: Superintendent Debbie Critchfield’s $45 million Idaho Career Ready Students (ICRS) grant program and a $15 million infusion by the Legislature.

Bonus to the investment: Idaho teenagers like CTE programs – and they’re good at it.

CTE students are more engaged, graduate high school at higher rates and use industry-recognized credentials to land good paying jobs.

In Idaho, 94% of CTE concentrators (a junior or senior in a capstone class) graduated in 2023, compared to 80% of all high school seniors. And 95% of those graduates found a job, attended college or went into the military.

“High school was just something to get done,” said Mountain Home High School graduate Cristobal Orozco. “I didn’t enjoy any part of regular classes. If I went to college, it was gonna be for mechanics or welding. Other than that, I wasn’t interested in it.”

What attracts students like Orozco is the relevant, hands-on nature of career technical classes. They’re drawn to programming robotic arms, designing a company website, building a house from the ground up, diagnosing an automotive problem, rebuilding a transmission, managing a fish hatchery, welding tractor equipment and helping people with medical needs.

Orozco said, “My three years of auto mechanics taught me the basics of how everything works.”

What’s happening in Idaho high schools

Certified high school graduates are repairing cars, welding boats and handing out medications in local pharmacies.

Orozco, 20, used welding to attain financial stability in Jerome. He plans to buy his own home next year. The son of Mexican seasonal farm workers, he’s a valuable Daritech technician, experienced in pipe fitting, electrical, mechanical, fabrication and welding.

Orozco had no interest in traditional academic subjects. Welding and auto mechanics kept him engaged, while providing a career path through multiple semesters of hands-on experience and several industry certifications.

At the Albertsons in Mountain Home, Aspen Everett, 19, is happy she chose the pharmacy technician option during high school.

“My teacher said that it would be a good opportunity to get a job right after high school,” Everett said, who was married last year and plans to pursue a degree in nursing while continuing to work in the pharmacy.

Mountain Home High School’s health professions program was recognized as the exemplary program of the year. Both the certified nursing assistant (CNA) and pharmacy programs have a 100% pass rate for industry certification exams. A majority of Mountain Home CNA graduates work in their profession while finishing a two- or four-year nursing degree. The remaining usually enlist in the military and work in the medical field.

The latest data ranks Idaho third among neighboring states for the percentage of high school students enrolled in CTE classes. More than 80% of students in Utah and Oregon are in programs, while Idaho sits at 71%, which is 72,000 students for the 2022-23 school year. Wyoming, Colorado and Montana are all below 60%.

Most high schools from the Treasure Valley to the Magic Valley report waitlists in their most popular programs. At the Meridian career technical center, there are 20 students waiting for a spot to open in welding; 48 for automotive repair; 26 for collision repair; and 10 for introduction to small gas engines.

“I can’t even add another program because I have no room,” said Beverly Hott, the CTE coordinator for Idaho Falls, Firth, Ririe and Shelley school districts. Her Career Technical and Education Center in Idaho Falls is one of 15 in Idaho, providing programs to students from multiple high school boundaries.

To meet the coming job demands, regional career technical centers like the new Portneuf Valley Career Technical Education Center in Pocatello will offer 21 career pathways, seven of which lead directly to an industry job after high school. PV-Tech used a local plant facilities levy and federal money to purchase the old 78,000 square-foot Allstate building. The state provided a $6.5 million ICRS grant to complete expansion and renovation. The center expects to be fully operational next year.

“I don’t know very many people who don’t want kids to succeed, because they’re smart enough to realize this is the next generation that’s working in America,” said Rhonda Naftz, Pocatello-Chubbuck School District’s longtime career technical education administrator.

Idaho’s industry needs

Premier Technology has 400 employees who generate $100 million annually through engineering, project management, manufacturing, machining and other services. The company could double in size but can’t because there are not enough trained workers.

“I’m so frustrated,” Sayer said. “They don’t have in their pipelines the graduates and the students to even come close to filling the demand.”

According to research from the Idaho Workforce Development Council, welding should expect double-digit job growth in the next five years in areas like Tungsten inert gas and fabrication welding. The demand for welders in Idaho is 64% above the national average and the median salary is $45,000.

The median salary for licensed pharmacy technicians is $38,300. Over the past five years, Idaho’s growth rate surpassed 30% and that’s expected to continue. There were 746 job postings in the last 12 months, the council reported.

In the heart of the Magic Valley, Jerome is home to Idaho Milk Products, a large-scale factory billowing steam with plenty of pickup trucks in the employee parking lot. But behind the factory’s facade is a diverse company looking for local talent in accounting, finance, sales, marketing and engineering.

“The biggest problem is that people look at these factories and they think this is where they are milking,” said Steven Christiansen, vice-president of human resources and organizational development. “They don’t realize that every one of these companies is a microcosm of a normal university or company.”

Idaho Milk Products actively courts local students with an outreach program that starts with being an industry partner for high school career technical programs, summer apprentices and college internships. The company started 15 years ago and employs 225 workers.

“We want to be the preferred employer for those kids that are suited to work in our industry,” Christiansen said. With a shortage in maintenance, electrical, utilities and mechanics, companies like Idaho Milk Products are developing their own workforce, and increasingly relying on high schools to create an interest in the trades.

“So if I can get that person that says ‘Hey, I want to go to that career tech program in the high school to learn sanitary welding, I can immediately go find a job in a very, very profitable profession,’” Christiansen said.

Data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report. EdNews photographs by reporter Darren Svan.