Back-to-back safety threats, miscommunication, and heightened anxiety drove district leaders in Blackfoot to make an unprecedented decision last week — to close down schools for a day.

The threats were investigated and resolved, and students remained safe throughout the incidents, said Blackfoot Superintendent Brian Kress.

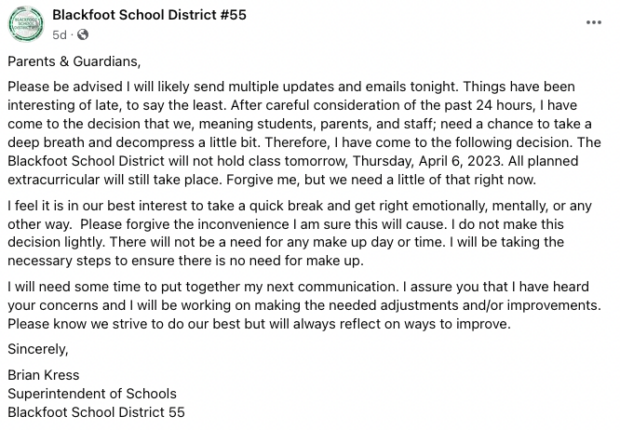

But after two safety concerns and a stressful 24 hours for parents, staff, and students, everyone needed a reset. Kress canceled classes on Thursday, April 6, to give community members — himself included — a chance to “take a deep breath and decompress.”

“I feel it is in our best interest to take a quick break and get right emotionally, mentally, or any other way,” Kress wrote on a Facebook post.

The unexpected day off gave Kress and his staff a chance to discuss, reflect, and make a better crisis management plan for next time.

This week, Kress shared some of the lessons learned with EdNews — like how to communicate more effectively, how to better familiarize parents with safety drill language, and the need to practice drills more often.

What happened: a timeline of a hectic week

Last Tuesday evening was the start of a tumultuous 24 hours in the Blackfoot School District, filled with multiple school safety concerns; anxious students, staff and parents; and ultimately — canceled classes.

Here’s what transpired:

Tuesday, April 4: First safety concern

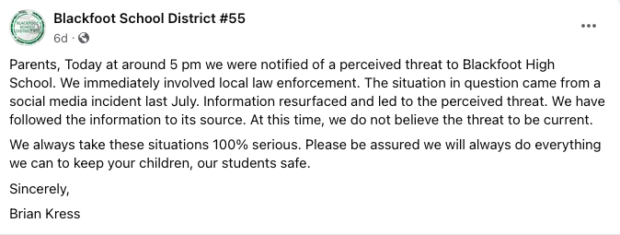

- Perceived social media threat: At around 5 p.m., a parent notified school officials about a social media post that posed a perceived threat to Blackfoot students. Law enforcement investigated and found it was a resurfaced post from a social media incident last July that posed no current threat.

- Communication: Kress notified parents that the threat was investigated and resolved. He sent out messages via Infinite Campus (the district’s student information system — where parent contact information, student grades, and communications are managed) and Facebook.

Wednesday, April 5: Second safety concern

- Social media threat: A second, unrelated threat was made on social media by a student who was not on a school campus that day.

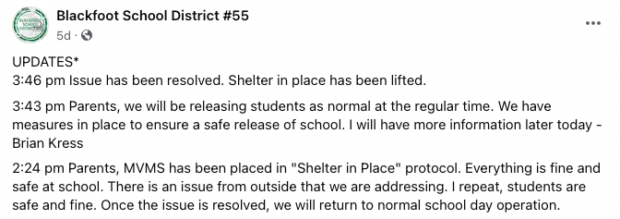

- Shelter in place: At 2:24 p.m., Mountain View Middle School went into “shelter in place” protocol (instruction goes on normally and students are kept inside the building because the perceived threat is outside the building).

- Communication: Kress communicated this via a Facebook post before he communicated via Infinite Campus (a decision that upset some parents who didn’t see the post).

- Shelter in place lifted: At 3:46 p.m., the “shelter in place” protocol was lifted.

- School canceled: Kress announced Wednesday evening that school was canceled for the next day.

Reflecting on missteps: lessons learned

So how did the social media posts and safety concerns lead to school closures? Kress and staff members used their time Thursday asking just that.

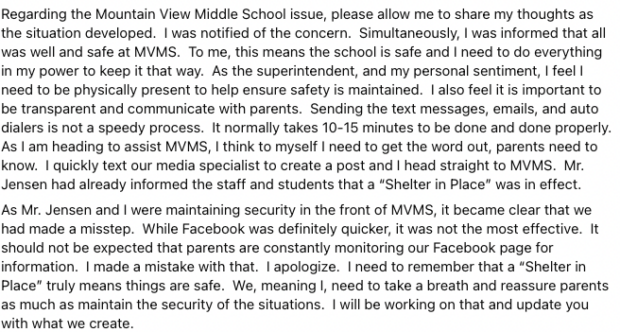

One misstep was the way Kress communicated about the second threat. On the way to Mountain View Middle School, he decided to communicate about what was happening via Facebook.

But not all parents are on Facebook or get notifications, so some were frustrated and felt out of the loop.

Instead, Kress said he should’ve communicated via Infinite Campus, which would send out texts, emails, and voicemails to parents. It’s a slower, more involved communication process, which is why he initially skipped it. But that meant the most direct stakeholders — parents of Mountain View middle schoolers — weren’t necessarily informed first.

“The number one priority (should be) reaching the impacted people,” Kress said. “I learned a lesson and I’m going to adhere to that priority protocol now.”

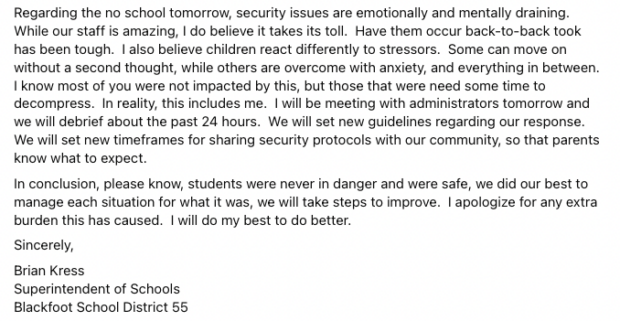

Kress also apologized for his choice on Facebook Wednesday night:

Another lesson learned: Active shooter drills and other safety protocols can be “traumatic” for kids, Kress said. But not enough practice can also have negative impacts.

Currently, Blackfoot School District practices shelter-in-place drills about twice a year (the number recommended by Idaho’s School Safety and Security program). But Kress said the district will now increase those drills to about four to five times a year.

The increased practice will help better familiarize kids with the protocol, and will also help parents learn and understand the district’s language regarding drills so they can respond more calmly, Kress said.

Last week, some were unfamiliar with and alarmed by the term “shelter in place,” which involves keeping students inside a school building (further details would jeopardize the confidentiality of the school’s ‘playbook’ for handling threats).

On Thursday, Kress wrote a series of posts on Facebook about his reflections on what had happened and plans for going forward.

“School tragedy is my greatest fear,” he wrote. “It truly keeps me up at night … but the reason I do what I do is kids give me hope. Hope and trust that a whole lot of good is out there. We just need to notice it.”

Online, comments were widely supportive as Kress provided updates over the chaotic week.

“Wow, It’s sad and scary that something like this has to even be considered,” one commenter, whose Facebook name is Chris Allison Burkman, wrote. “But thank you for what you are all doing to keep our kids and staff safe.”

Communicating during crises is often a “chokepoint” for schools

The Idaho School Safety & Security program has developed common terms for drills that districts can adopt so language is more consistent statewide (shelter in place is not one of the terms). But Mike Munger, program manager for ISSS, said in some communities it might make more sense to stick with the terms they’ve been using for years.

As far as sending messages, Munger recommends districts use their school information system — such as Infinite Campus or PowerSchool — because it will have the most updated contacts for parents.

But communication during high-stress scenarios tends to be challenging: “That seems to be the place where big failures tend to occur.”

“Usually the chokepoint that we see in schools isn’t that they don’t have the tools — it’s that they don’t have the people.”

Not all districts have a designated spokesperson, so that duty can fall on individuals who are making the high-pressure decisions.

“You can either manage an emergency or you can talk about it, and you usually can’t do both,” Munger said.

And it’s difficult to communicate to thousands of households via their preferred mode — phone call, text, email, or social media post.

“You start to see why that’s a really tall order,” Munger said.