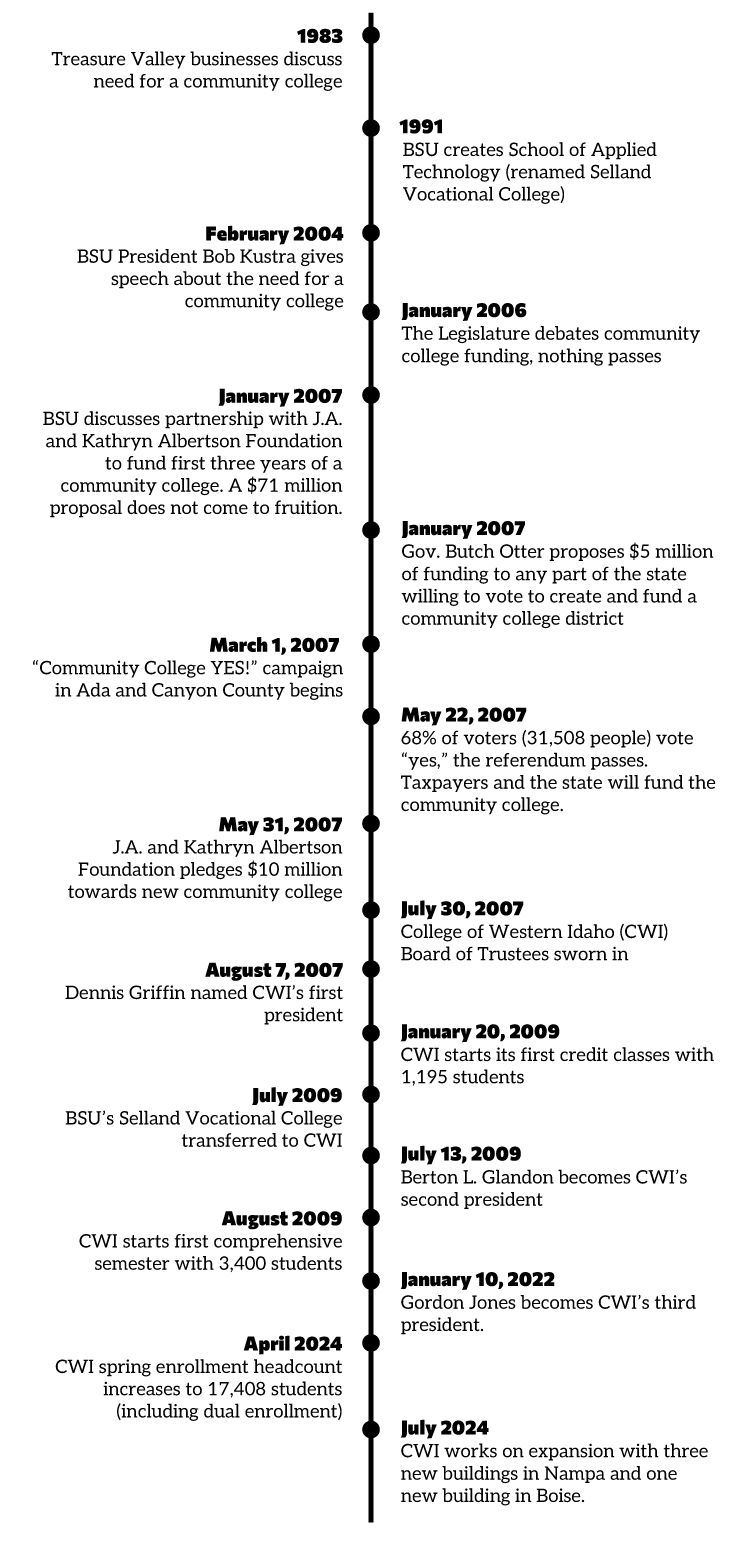

The College of Western Idaho started with 1,000 students in January 2009 and has grown to serve over 30,000 students this past year. This series of stories tells the past, present and future through the voices of those who started the college and those who work for and benefit from it today. The series includes a glance at the numbers: the demographics, the programs, the classes, the costs and the timeline.

Cheryl Wright was surprised to find there wasn’t a community college in the Treasure Valley when she moved to Idaho in the early 2000s to work at Boise State University.

At that time, the growing Treasure Valley was the largest metropolitan area other than Washington, D.C., with no community college.

Selland Vocational College, a part of BSU, was the closet thing to a community college in the area. But as BSU expanded, President Bob Kustra sought to focus on research and graduate education and shift the community college responsibilities to a new entity.

Wright had a fondness for community colleges, having started her post-secondary journey at Northwest College in Powell, Wyo. She wanted to work for a community college, so she was energized over conversations about starting one at BSU and in the community.

The conversations led to plans.

Kustra, the Nampa Chamber of Commerce, legislators and Gov. Butch Otter began talking about the potential for taxpayers to vote in a referendum to fund a community college.

That began the tale of the College of Western Idaho.

Getting the plans in motion

Gov. Butch Otter pledged $5 million of funding to any part of the state willing to vote to create and fund a community college. This spurred the Community College YES! campaign.

The referendum vote included both Canyon and Ada counties. Two-thirds of voters averaged between the two counties would need to vote yes. Wright excitedly worked on the campaign in her free time, making phone calls to get the word out.

Stan Olson, then the superintendent of Boise School District, also became part of the efforts. His involvement was partially personal — his mother had attended a community college at age 50.

He and other volunteers used the BSD’s rich network of community groups with a successful track record of passing bonds to coordinate efforts. The Meridian School District (now named West Ada) followed suit.

Campaigners used mail-in ballots for the first time in Idaho, tracked the ballots and called 5,000 people to ask them to return the ballots. More than 30,000 brochures were handed out to targeted homes, according to the book “From Scratch” by the College of Western Idaho’s first president, Dennis Griffin.

Not everyone supported the idea of a community college.

Mark Dunham, one of the CWI’s first trustees, said: “I heard people saying, ‘BSU already has a tech school. Why do you need this?’ And, ‘We don’t need any more taxation.’ ”

A majority in the Legislature also showed hesitancy, denying organizers a request to lower the threshold to a simple majority to pass the referendum.

After $400,000 and thousands of volunteer work hours, the day of the referendum arrived — May 22, 2007. It passed with 68% approval, carried on the wings of Ada County’s 70.53% approval. (Canyon County voted slightly below the supermajority at 62.18%).

“When it passed really late that night in May, I was shocked. And incredibly happy,” Dunham said.

Wright was also elated.

“I was so over the moon ecstatic because of my experience,” she said. “It almost felt like my destiny. I was going to be part of a community college, and a brand new one was even more exciting.”

Creating the vision

The first step to starting the college was selecting a board of trustees. Dunham was one of over 100 people chosen for one of five unpaid trustee spots.

Dunham recalls being sworn into office by State Board of Education President Milford Terrell, who then laughed and said, ‘Good luck!’”

“At that point we had no staff, no telephone … we had nothing, no infrastructure,” Dunham said.

Despite their humble beginnings, the trustees had big dreams.

“We didn’t just want to be this cookie cutter community college. … We wanted to make it different — more innovation,” Dunham said.

The Idaho Statesman asked the five new trustees about their goals for the community college in August 2007. They said they aimed for the college to offer the following:

- Academic transfer programs.

- Two-year degrees and certificates.

- Adult basic education and GED classes.

- Small business development.

- Advanced placement classes.

- Noncredit lifetime learning classes.

“(CWI) will offer all citizens, regardless of race, age, income, race or disability, a wide range of educational and training opportunities, which will foster and promote personal growth and fulfillment,” trustee M.C. Niland wrote.

The trustees also wanted relationships with Treasure Valley businesses.

“A lot of the corporations in Treasure Valley had high expectations that we would partner with CWI and the business community … so we did surveys of the business community and asked, ‘What kind of training do you need?’” Dunham explained.

Building the college

Trustees hired the first college president, Dennis Griffin, in January 2008.

That’s when Wright’s longtime professional dream came true.

“I got a call to meet him in the dean’s office. I knew I wasn’t in trouble,” she said, laughing.

Griffin asked her to be CWI’s vice president of finance and administration.

“I didn’t have to apply! And I was thrilled, so thrilled,” Wright said, fighting back tears as she recalled the conversation. “The start of that college was amazing.”

Wright joined the team of individuals that worked to prepare the college for its first students.

“I worked 70 hours a week, every week, for the first five years,” Wright said. “I was so excited. You couldn’t prevent me from working.”

Development was not without complications, however.

“Everyone was creative, but from a finance and administration point of view, at times a challenge,” Wright said.

Even so, Wright said the community came together to launch CWI. There were several components, including:

- The Community College YES! campaign.

- The governor and his seed money.

- The State Board of Education’s advocacy.

- The J.A. and Kathyrn Albertson Family Foundation’s grant funding.

- Legislators who advocated for CWI.

- BSU donations of land and staff.

CWI opened to students in January 2009, less than two years after the referendum vote. By 2011, it would cater to almost 12,000 students.

“Long story short – right time, right discussion, right people involved, right level of support and people embraced the need,” Olson said.

About 15 years later, the school serves over 30,000 students. About half of of those students are in traditional classrooms, with the rest in a mix of hybrid, online or apprenticeship courses. The school has 1,233 employees.

Disclosure: Idaho Education News receives grant funding from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.