Cory Rock loves excavators and bulldozers, not traditional school. He had no interest in higher education, so he joined the military after high school.

“The stuff I was interested in, I did really good. But math? English? No,” he recalled.

Rock represents one of the main goals of the College of Western Idaho since it started in 2007 — connecting students seeking employment with businesses in need of workers.

After his stint in the military, Rock discovered the College of Western Idaho’s Heavy Equipment Technician Program, and thought it would be a perfect fit for his interests and background. He’s currently working on his associate’s degree and has a part-time job with Vermeer, an industrial and agricultural equipment company that partners with CWI. He plans to work there full time once he completes his degree.

“It’s nice because you come to school and learn in the morning, and then go to work and apply,” Rock said. “They put us on specific jobs we’re learning in school.”

“Affordable, quality, accessible education.” — CWI President Gordon Jones describing his institution of higher education.

In just 15 years, CWI has blossomed to an institution serving over 30,000 students, and expansion is a continuing theme.

“I honestly believe CWI and our community colleges right now are the single best embodiment of what public higher ed was intended to be, which is open access and high affordability that gives you options that go beyond your family of origin,” said CWI President Gordon Jones.

Jones, an educator and administrator with a business background, said expansion should be innovative and meet the ever-changing interests of students and the needs of businesses.

Since Jones started as president in January of 2022, the college has continued to grow and evolve:

- Student enrollment continues to rise, despite the stagnation of the number of Idaho high schoolers choosing college. CWI could potentially have as many as 50,000 students in the next 15 years.

- Gov. Brad Little’s Idaho LAUNCH program will incentivize students who can get up to $8,000 for college or workforce training aligned with in-demand careers.

- Four new buildings are being constructed, including:

- Nampa Health and Science Building (fall 2025)

- Nampa Horticulture and Agricultural Science Building (fall 2025)

- Nampa Student Learning Hub (fall 2026)

- Boise Campus (fall 2026)

- The college will offer its first four-year degree, a Bachelor of Applied Science (BAS) in Business Administration, after some debate and opposition from local universities.

- The number of programs offered continues to increase, with over 121 programs currently.

CWI board chair Molly Lenty, who spent 25 years as a business leader at Wells Fargo, said the school’s growth should make business sense and be beneficial for the college.

“Just like running a business, we are evaluating what the market looks like,” Lenty said. “What resources do we need? How do we need to innovate?”

This includes new building projects, which not only seek to free the college of leased spaces not customized for their programs but also give students a more central hub for classes.

“I’m unabashedly supportive about spending money for first-rate teaching space and having a campus where students can actually come and not have to drive between classes to different buildings,” Jones said.

Because there is no on-campus housing at CWI, these new buildings seek to help build community and identity among students.

Jones says the state “understands” the need for these buildings, giving 30 million to the efforts.

CWI received over 19 million dollars in state funding this year, around 1/3 of the state funding for community colleges- though they have 47% of community college enrollment. In 2015 total revenue for CWI sat at around 54 million dollars, for 2023 around 75 million.

CWI administrators have much to balance as they look to the future: the changing landscape of higher education, the growth of the Treasure Valley and the business needs that come with it and the ever-evolving needs of their diverse student population.

Finding balance in expansion

CWI is increasing in size and scope, despite the fact that Idaho’s “Go On” rate of students moving from high school to college sat at 42% in 2022, 18% lower than the state’s goal.

CWI also has grown despite some pockets of hesitancy around higher education locally and nationally. GOP delegates debated the merits of taxpayer funding for higher education at their state convention, including adding a vague statement in their platform that they “do not support using taxpayer funding for programs beyond high school.”

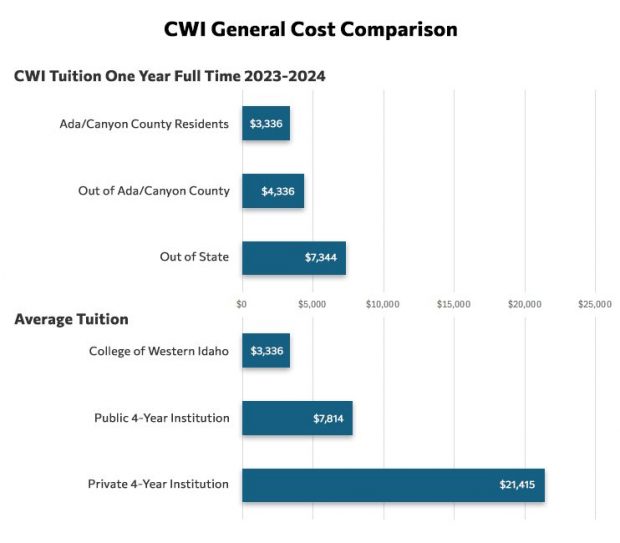

Despite this, Jones says one of the major appeals of CWI is its low cost.

“The affordability of a community college can’t be beat,” he said. “That’s the most affordable path.”

Lenty said CWI’s transparency about program costs and potential earnings also attracts students.

The Heavy Machinery program website lays out the costs for a degree or certificate, as well as potential earning. This information is available for almost every program.

Lenty explained that some larger universities lack transparency, often leading to students choosing low-earning majors, a problem exacerbated by student debt.

Along with transparency, employees of CWI strive to be innovative when things aren’t working for students, something Assistant Professor Liza Long says can take longer to do in a university setting.

Long described how several years ago CWI’s version of a “first-year experience” class, CWI 101, was seeing students dropping the class or leaving the college soon after taking it. Long was serving as chair of the general studies department at the time, and she and her team investigated these trends. They decided to reframe the class completely, instead calling it, “Pathways to Career.” Students then researched and reflected on their career goals during the course.

These changes led to a substantial uptick in the number of students passing the course as well as in overall persistence rates at the school. Students commented that the course helped them either affirm why they were choosing their career, or in some cases reevaluate their choice.

Long said she loves “working at an institution where students are at the center, and the decisions that are made are data driven and people are willing to try new things.”

Matching business needs and student interests

Jones says they often choose what programs to offer by looking at both business demands and student interest.

For instance, CWI just started electric vehicle technician training in partnership with Tesla and Rivian in response to the growth in the number of electric vehicles on the market.

Students, however, also played a role in the decision.

“We also knew there was a lot of interest in good paying jobs in the automotive service,” Jones said. (Automotive Technology has the third-most graduates of all CWI’s CTE programs).Tor

Still, not all students have the passion for technical programs.

Take CWI student Andy Del Toro Obeso, who is studying political science at CWI.

Del Toro Obeso grew up in a family that struggled financially, and his parents, after working fast food jobs for most of their lives, wanted more for him and his siblings.

Though he couldn’t afford a four-year university, Del Toro Obeso used federal grants to pay for CWI.

“Not a cent came out of my pocket,” he said.

While in school, he is working on political campaigns and hoping for a career in politics.

“I want to change society,” he said. “I want to reform it in a way that makes life worth living.”

Jones says there is also room for students like Del Toro Obeso, who are interested in programs like political science.

“I want students to have a choice,” he said.

Jones also emphasized that many CWI students “have an Idaho work ethic” and “are coming in expecting to work.” Jones said some businesses just need quality employees who are “willing to get to work right away.

“I’m finding many of our employers are flexible about whether you have a two- or four-year degree.”

Whether general studies students end up transferring to a four-year university or finding a job right after their two-year degree, Jones wants their education to provide them with marketable skills.

Measuring student success

As CWI expands to serve more and more students, it also must keep track of their success.

But determining “success” can be tricky. For example, a student who starts a two-year welding degree may gain enough skills to become employed after the first year and not finish the program. Despite having reached their goal of finding meaningful employment they will not be reflected in graduation-rate statistics.

Jones and Lenty both believe that traditional metrics like graduation rate show an incomplete picture of student success. The college’s graduation rate, for example, is measured as being less than 1,000 students each year because it only looks at full-time, for credit students.

“Completion looks different at a community college level,” Lenty said.

Jones said the college is working on ways to “report about economic empowerment that comes from CWI.”

Currently, it sends post-graduation surveys to students to ask about employment. The college also makes sure to pay attention to enrollment and retention rates.

When it comes to supporting students already enrolled, one method is a computer program which automatically flags students who need extra help.

Lenty said when coaches and instructors use this program, “(it) has helped our students to overcome whatever barrier it might be. Sometimes it’s financial, sometimes it’s child care, sometimes it’s transportation, any number of different barriers. It’s like, ‘OK, let’s just figure it out. How can we really be a team to help you be successful?’ ”

The fact that students are paying less for their education also means the stakes are lower for them to change their minds about the education they want to pursue — or even take a break if needed.

Jones said this aligns with generational trends.

“For this generation, it’s much more clear that (they’ll) have chapters in their life,” he said. “You may only weld for eight to 10 years, but then you go into sales for a company, and then you actually go to work for the state or you go back and learn to be a pilot.”

Administrators believe CWI’s affordability grants that opportunity of flexibility as well as the ability to take less traditional paths to employment.

Jones and Lenty think an awareness campaign is important as the college continues to make decisions regarding its growth, and they want high-level decisions to be transparent and involve stakeholders.

“We’re designing ourselves and preparing to serve larger and larger numbers,” Jones said.

EdNews’ Randy Schrader contributed to this report.