Elise Doyle pulled on the gold cord around her shoulders, steadying her nervous hands as she walked onto the floor of the Ford Idaho Center. She scanned the crowd for her family. The day had finally arrived.

After years of financial stress, leading to unstable housing and half a dozen different schools, Elise had made it to graduation.

“It’s a big accomplishment for me,” she said in an interview weeks before. “I finished it. With good grades. And on time.”

One in 150,000:

About half of Idaho public school students — or 150,000 children — qualify for free or reduced price lunch, a measure the federal government uses to gauge poverty.

Elise has qualified for the program her whole life.

She qualified in elementary, when she bounced from school to school depending on where her family could afford to live.

She qualified in middle school, when she helped take care of her siblings, cooking and cleaning for a family of six.

And she qualified in high school, when she worked nights at fast food restaurants to help pay the bills, and juggled her responsibilities on four hours of sleep.

Statistically, students like Elise are less likely to succeed in school. Last year, students who live in poverty scored 24 percent lower on state tests than their more wealthy peers. One in every four economically disadvantaged students will drop out before graduation.

“She is the exception,” said Olivia Lile, Elise’s government teacher. “Most kids in poverty struggle through school. Most of the time they don’t see the importance.”

Elise never had a doubt.

“If I didn’t have an education, I didn’t have much. I didn’t come from a family with money, or a family where you could inherit the business, or anything like that,” she said.

“I’ve always told myself I was going to have a better life.”

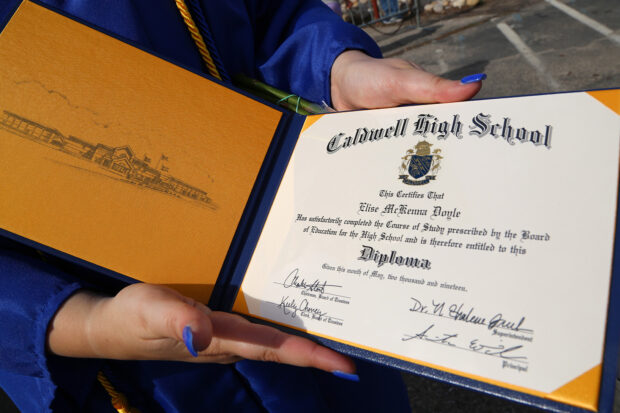

On May 20, Elise graduated from Caldwell High School with a 3.5 GPA, blue and gold honors cords draped around her neck.

Elise’s Journey

Elise Doyle was born in Boise 18 years ago and named after a character in one of her grandmother’s favorite movies.

Grandmother Cheri Doyle didn’t just name Elise, she helped raise her. Elise’s mother went to prison when Elise was five, she said, so grandparents Cheri and Jim added her to a group of cousins living under their roof.

Cheri would sit her granddaughters around the dining room table to teach them things a young lady should know.

One of those talks in particular seemed to resonate with Elise.

“I told them: Life is hard when you’re a woman,” Cheri said. “Put your education first. Learn as much as you can, so you can take care of yourself. Don’t depend on anybody else. And she took it to heart.”

Of her grandchildren, Elise was “the most interested in hitting the books,” Cheri said, even when the going got tough.

It got tough.

First through fourth grade are a blur for Elise. She moved back in with her mother and welcomed two half-siblings to the family. They moved frequently around the Boise area, seeking out affordable rentals.

Neither Elise’s mother nor her stepfather worked steadily, Elise said. They relied on food stamps and welfare to get by.

Elise used to take a calculator on grocery trips to watch the food stamp budget. She cooked a steady stream of Hamburger Helper, or sometimes meatless spaghetti if supplies ran low at the end of the month.

As far back as she can remember, Elise was caring for her siblings. After school, she would help the children with homework and make them dinner. She’d clean the dishes and the laundry, sometimes enlisting the help of the younger ones for chores.

“She never went out and had a good time,” Cheri said. “Basically, she never had a childhood.”

Elise lived in Boise until her sophomore year of high school, when her family was evicted from their home when the landlord decided to sell, she said. That summer, her family moved back in with Cheri and Jim. The house was so crowded, some of the family slept in tents in the back yard.

The move prompted a new wave of instability for Elise, then halfway through high school.

She moved districts, starting school at Caldwell High her junior year. She picked up a new job at Dairy Queen, tried to find new friends in a new city, and rallied to improve her grade point average, which was dented by transferring credits.

Then, after just one year in Caldwell, another major shift: Elise’s family decided to move to rural central Oregon. Without a place to live, they stayed with friends, Elise said. She and her siblings slept on floors. Her parents slept outside.

“Not knowing where you’re going to live, having to sleep in a tent, it really sucks,” she said.

For a time, Elise wondered if she should stop going to high school that year and just get her G.E.D.

The Certified Nursing Assistant program spurred her on. She left Oregon and returned to Caldwell, living with her boyfriend’s family while she finished her senior year.

“Caldwell has been the savior of everything,” said Elise’s mom, visiting from Oregon for her daughter’s graduation. “For people that are low income, it’s very hard to get out of that…so, being able to have the opportunity to graduate with a CNA has made it so much nicer, and given her opportunities that she would never get any other way.”

The impacts

School has always come easy to Elise, who says that despite her moves and busy schedule, she didn’t really struggle with classwork. Still, the financial pressures on her academic experience were inescapable.

Elise always wanted to try out for the girls wrestling team, for example, but never did.

“Any money I had had to go to my phone bill if I needed a phone, or milk if we needed milk,” she said. “…I wasn’t able to do anything extra.”

She didn’t have a computer at home until her junior year, when her family pulled together to gift her one. If a teacher asked students to type a homework assignment, Elise would ask if she could write it out nicely in pen. Usually, teachers were OK with that. If they weren’t, Elise had to plan how she could use library computers after school. She had to find a way home and make sure someone could make dinner for her siblings.

“I couldn’t just go home and do homework,” she said.”…I had to do things differently.”

And time for homework wasn’t always easy to find, either. By 14, Elise had her first job working nights at McDonald’s to help pay the bills. She’d get home at 11:30, still have to eat and do her laundry, then be up by dawn to zip through homework and marshal her siblings for school. Missing the bus meant missing school, because there wasn’t always money for gas.

“I just had to really make sure that I was on top of things,” Elise said.

Elise’s struggles are not unique — not in Idaho or in Caldwell, where so many kids qualify for reduced priced meals that all students get food for free. Her classmates are coping with similar things.

“Most of our kids in our community, especially Caldwell High School, have been poor,” Caldwell high senior Abigail Ramirez said.

Ramirez has missed school, and watched her grades drop when she had to get a job to help support her family. Some of her friends have done the same.

“We have kids out here who can change the world,” Lile said. “But because of their economic disadvantage, they don’t have the ability to reach their full potential.”

Elise included.

“She could have been valedictorian,” Lile said. “It’s not that she wasn’t capable. It’s that the economic disadvantage of it all made it more difficult.”

Whatever her struggles, Elise said her first 18 years ended the way she wanted them to: with a high school diploma.

In the coming months, Elise plans to test for her Certified Nursing Assistant certification. She’s working at Pizza Hut, trying to save the $2,000 she’ll need to study for an Emergency Medical Technician course at the College of Western Idaho. She’s engaged to her high school boyfriend, and plans to get married this month.