If a Lapwai Middle/High School student needs a snack to get through the day, they just have to ask a staff member during their passing period.

If a student is struggling in the classroom environment and needs a place to collect themselves, they can work from the school’s softly-lit “empowerment room.”

And if they’re having a mental health crisis, therapists can be on-site in minutes, from the local health clinic right next door.

The 500-student Lapwai School District takes an all-bases-covered approach to student well-being, including leveraging partnerships with the Nez Perce tribe and local community to address youth mental health. The small North Idaho district is among only nine rural districts in the state to provide four key behavioral health supports for all of its students, according to an Idaho Education News review of State Department of Education data.

“That’s probably how we help our students most. We’re very proactive, and we make sure we’re giving them everything they could possibly need,” said Iris Chimburas, dean of students at the middle/high school.

Lapwai’s multifaceted approach to student behavioral health includes teaching social and emotional skills and positive behavior expectations, emphasizing restorative justice over punishment, partnering with local agencies for easy access to therapy and incorporating Nez Perce culture at every turn.

The approach has shown improvement in youth behaviors at the elementary level. It’s a work in progress at Lapwai’s middle/high school, where Chimburas has restructured behavior and discipline systems to better meet students’ needs.

Elementary students thrive on consistent expectations

At the heart of Lapwai’s approach is a philosophy called Positive Behavior Intervention and Supports (PBIS), one of the most commonly adopted frameworks for addressing youth behavioral health in Idaho. Lapwai has tweaked the model to fit the cultural context of the majority Native American school on the Nez Perce reservation.

PBIS focuses on teaching and acknowledging positive student behavior. Posters of youth during a district Pow Wow dot Lapwai Elementary School, covered with the phrases “Be Respectful,” “Be Responsible” and “Be Safe” in the Nez Perce language.

Teaching and reinforcing those expectations consistently helps improve student behaviors and academic performance, elementary PBIS coordinator Julie Clark said.

The approach can also be important for youth mental health, said district psychologist Lori Ravet. A student who comes from an unpredictable home environment, maybe an abusive situation or a home where a parent struggles with alcohol abuse, might not know what to expect from adults or be hypervigilant and have a hard time learning. Done well, Ravet said, PBIS creates consistency among adults in the school building, and an environment that helps students feel safe.

“The whole system is exactly what you need for a child coming out of trauma, or a child who is just new to the system, which is: I know exactly what I’m going to get from all of the adults in my life in this school system,” Ravet said.

Elementary students also learn a social-emotional curriculum designed to help them regulate their emotions, develop self-confidence and build empathy for one another.

Over a decade of implementation, PBIS has shown marked gains in reducing behavioral challenges at Lapwai Elementary. In the 2013-14 school year, Lapwai had more than 1,500 behavioral referrals. By 2018-19 school year, that was down to 626.

Measuring behaviors can be helpful to gauge the mental health of students who act out, or externalize their stress, Ravet said, but it’s only part of the picture. She’d like to use universal screeners to better capture students’ internal emotional health as well, but says those are expensive and time-consuming.

“I’m hoping that, as we continue to progress as school systems, we can … in an even better way identify the needs of the whole child,” Ravet said. “We’ll get there. We’ve made a lot of progress.”

The system needed to be redesigned for older kids

Chimburas started over with PBIS at the middle/high school.

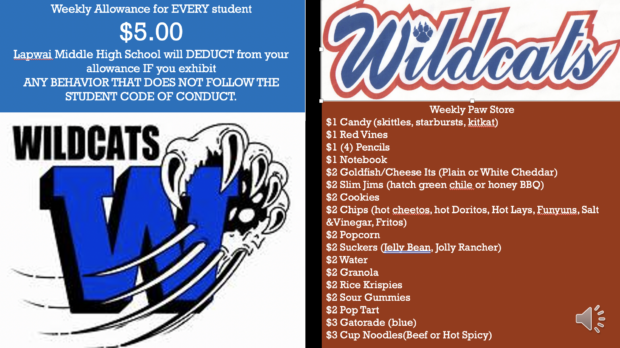

A key component of PBIS is that students are recognized and affirmed for positive behaviors, she said. The school’s inconsistent rewards system, where kids could earn “paws” dollars for good behavior, wasn’t doing that.

Chimburas scrapped the awards system to give every student a weekly allowance instead. Students can use their allowance to buy snacks or candy from a campus store, and have money deducted for things like being tardy to class.

It’s a small technique, but Chimburas has seen it work. She remembers one student in particular, a senior who was frequently in trouble with administration, coming into her office to ask if he had an allowance. He was shocked that he did — $5 to spend throughout the week.

After that first visit, he’d come in frequently to check his allowance. He started saying hello to Chimburas in the hallways and buying in to campus rules.

“It impacted this student in a positive way, and I don’t think he got that very often,” Chimburas said.

That was just the start of changes at the middle/high school geared toward instilling optimism, belonging and pride in the school culture.

The district has Nez Perce language, art and history built into classroom learning. Chimburas also paired teachers, many of whom are non-native, with tribal members who mentor them and act as a direct connection to the local community.

“If you do research on intergenerational, historical trauma, you’ll see that education has not been a positive thing for Native Americans,” Chimburas said. “It’s something that we’re still seeing the effects of: Being removed from our homes, being forced to try to lose our culture, or way of life, even down to the way we dress, cutting off our hair and taking away our language. We are still affected by all of that today. It’s extremely important we incorporate our culture back into the education system.”

Chimburas also helped reform the school’s discipline process. The school created an “empowerment room,” where students who are struggling, or need a place to decompress, can work alongside high achievers. She established a new code of conduct, and requires teachers to try two interventions, such as reviewing expectations or meeting a students’ parents, before they can issue a discipline referral.

“When they’re acting out, those are red flags. It could be home life, it could be academics, anything that has to do with the child — something is wrong,” Chimburas said. “When they come to school, they’re depending on us to support them, not only academically or socially and emotionally, it’s our job to support 100 percent of that child.”

Chimburas was starting to see a change before COVID-19 sent Lapwai students to a new hybrid-learning environment. Behavior referrals at the middle-high school dropped from 402 in 2018-19 year to 273 in 2019-20. Suspensions were also down from 96 total in 2018-19 to only 16 in 2019-2020.

Her goal is to move the school from a zero-tolerance discipline system, which can lead to more suspensions and lower graduation rates, to a restorative-justice approach that focuses on correcting wrongdoing over punishment.

Helping students means understanding their personal story

Lapwai leans on partnerships with the Nez Perce tribe and local agencies provide student mental health supports.

Therapists from the Nimiipuu health clinic work from the school building some days, and also see students at their building next door. Therapists host group sessions for youth struggling with grief or substance use disorders. And if a student has a mental health crisis during the school day, Nimiipuu staff is on site in minutes.

“This is truly where we shine. We have an incredible collaboration with the tribe,” Ravet said. “Relationships are what make social emotional supports work in the Lapwai School District.”

Addressing youth behavioral health in a culturally responsive way means understanding the context of historical trauma that impacts Native American communities, but also that trauma is not a “cookie cutter issue,” Nimiipuu behavioral health manager Karen Hendren said. Her staff works to understand each student’s personal story, culture, religion and the treatments that would be best suited for them.

Therapeutic approaches might look very different from a traditional counseling appointment, Ravet said. Sometimes addressing students’ mental health needs means releasing them to go on a buffalo hunt, or incorporating culturally-based practices. For example, Ravet said, in the Seven Drums religion it is tradition to not mention the name of a person who has died for the next year. To counsel through grief appropriately in that context takes a unique approach, Ravet said.

“You have to be very culturally responsive in a different way that other school districts might not understand,” she said.

Lapwai’s youth returned to school buildings full-time this spring, back together in person for the first time in a year. While the pandemic disrupted the learning environment, Lapwai administrators say it also created a unique advantage. Teachers got to know students better when they taught smaller class sizes. And Ravet says she saw a drop in student suicide attempts during the pandemic year, perhaps because of reduced academic pressures.

“As psychologists, we really need to be thinking about: Did we learn anything in COVID that would better help our students academically, so that we would see less of the pressures of suicide?” Ravet said.

Read more in this series:

Sunday: Idaho’s approach to youth mental health was already scattered. Then COVID hit.

Monday: Calvin Loffer survived a suicide attempt. Now he has a message: Mental health can impact anyone.

Tuesday: In-school therapy in Nampa highlights the benefits, and challenges, of collaboration.

Wednesday: Cassia County aims to connect students with immediate mental health services.