Stephanie Lindholm’s usually happy boys were struggling. Her divorce from their father had been traumatic: not just the separation, but the turmoil and restraining orders that followed. The boys were scared, and acting out.

Stephanie’s oldest son, 8, struggled to stay on task and didn’t want to engage with family activities. Her kindergartner started to hit his brother, and to challenge Stephanie at every turn.

“It was so frustrating for me as a parent. I didn’t know how to help him, and I didn’t know how to help him process his emotions,” Stephanie said.

Stephanie’s sons attend Endeavor Elementary, one of the first schools in the Nampa School District to pioneer an in-school therapy partnership with Terry Reilly Health Services. The services have helped the boys with their behaviors, and their academics, Stephanie said.

“We can tell her what’s on our minds, tell her if we’re stressed or not,” Aydin Lindholm, now 10, said about his therapist. “I don’t have to be worried as much.”

Stephanie’s family, and many others in the Nampa School District, are benefiting from a partnership intended to make therapy more accessible for students, by providing the service at school.

Professional therapists see students at just over half of Nampa’s 24 campuses. Students don’t miss hours of class getting to their appointments, and parents don’t have to take time off work to get them there. Data suggests that students who access the therapy have better attendance, and fewer behavioral challenges, than they did before.

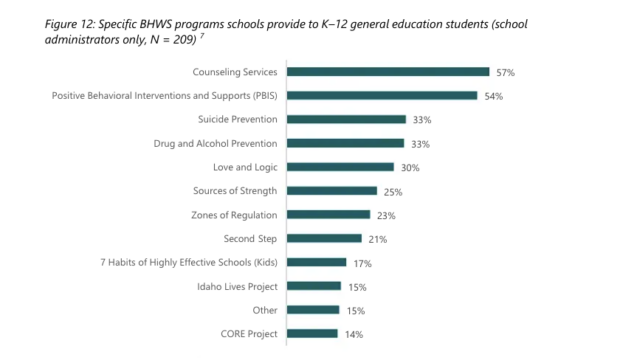

Counseling is one of the most common behavioral health supports that Idaho districts offer to students, according to a survey commissioned by the State Department of Education last year. Nampa’s model, which served as a pilot for the Blue Cross Foundation’s efforts to expand in-school therapy, offers insights into the benefits and challenges of partnering with outside agencies.

The partnership is free for the district, but it doesn’t come without effort. The collaboration has been stressed at times by therapist turnover. High demand means in-school providers often have waiting lists of students they don’t have time to see. And pandemic closures posed a new challenge when many students decided not to continue with teletherapy — even as national trends suggest they may have needed extra support.

Data suggests improvements in behavior, grades and absences

Whether students are dealing with traumatic events or processing changes like a parental divorce, they often need therapeutic help beyond the short visits to a school counselor, who deals with hundreds of students.

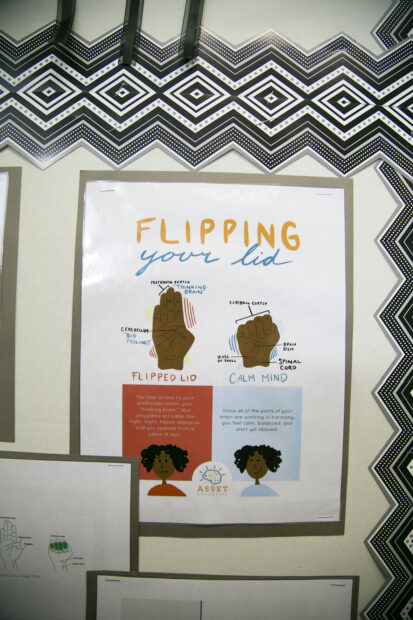

“Those little brains don’t know how to process what they’re feeling,” said West Middle School principal Chance Whitmore. “Having someone teach them the tools and the ability to work through it, gives them a chance to function on a day-to-day basis without being angry all the time, without being frustrated all the time, without acting out all the time.”

Trista Jackson used to lose sleep over students who needed intensive therapy, whose needs she didn’t have time to meet as the only school counselor for Endeavor’s 500 kids. Now she helps get those families in-school care through a partnership she helped establish.

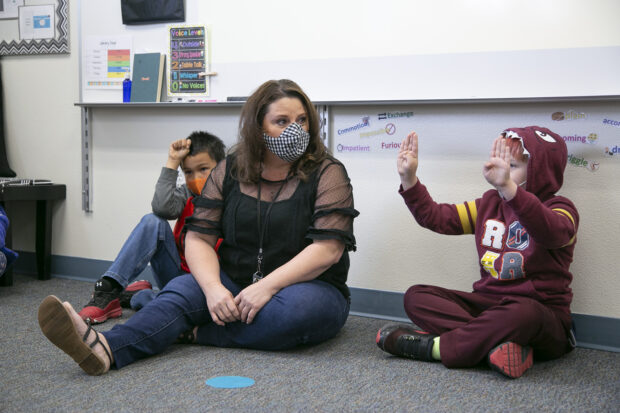

Jackson helps teachers and families identify students who could benefit from on-site therapy with Terry Reilly counselor Megan Forster. Students attend appointments during the school day and Terry Reilly bills parents or insurance the same way it would for outside services. Forster works with teachers to schedule a convenient time for the children to leave class, and with a parent’s permission, she can talk with school staff about strategies that might help them in class.

Forster’s hallway office at Endeavor is strewn with books, toys and a green beanbag chair, the preferred perch of her elementary-aged clients.

Endeavor staff interviewed Forster to make sure she’d be a good fit on the building’s team. In-school therapy can be a challenge for clinicians who work without the office supports of a clinic, but Forster enjoys the insight it provides into children’s lives.

“One of the coolest things about this job is that I get to see and learn and grow with them,” Forster said. “I get to be by their side.”

Teachers across the district carry examples of students who have worked through crippling anxiety, behavior challenges and post-traumatic stress with the help of in-school therapists. From a data standpoint, it can be tough to parse the specific benefits of therapy from the district’s other behavioral wellness initiatives. But an early study from the Blue Cross foundation found encouraging results:

- West Middle School documented a 53 percent drop in behavioral incidents and a 37 percent drop in absences among the students who participated in therapy during the first year of the partnership, in 2017-2018.

- Nampa High noted a smaller drop in absences and didn’t see any change in behavior incidents, but the average G.P.A of students in therapy increased about 12.6 percent.

Ethan, a student at Nampa’s Union High School, started to fall behind his sophomore year. He wasn’t paying attention in class, or he’d avoid going altogether. His brain strayed from academics to his parents’ turbulent divorce, and physical fights with his family that would escalate to police involvement.

Ethan’s homeroom teacher noticed the change. She called Ethan’s father, Kevin, and suggested Ethan might benefit from visits to the school’s on-site counselor. Ethan didn’t want to go at first, but eventually started opening up to the counselor, who felt like a friend.

“A lot of the things she taught me was just to kind of be aware of myself. Like, if you’re feeling anxious, what is it? Whenever you’re feeling something, why are you feeling that?” Ethan said.

Over the next year, Ethan went from the brink of dropping out to taking advanced classes at the College of Western Idaho.

“I know that part of the turnaround was that he had somebody at the school that he was comfortable with, and who was supportive,” Kevin said.

Turnover, waiting lists and COVID-19 challenge the partnership model

Nampa’s partner therapists reported a significant drop in the number of students who continued with therapy, or teletherapy, at the start of the pandemic said Shelley Bonds, the district’s executive director of elementary education. Therapists took on outside patients to make up for the drop in students, which meant therapy wasn’t able to return full-fledged when Nampa’s kids started coming back to school.

Even at full capacity, many of the in-school therapists juggle waiting lists.

“There always seems to be more need than there is space,” Whitmore said.

One of the biggest challenges has been turnover of therapists, district social worker Diane Brown said. Therapists leave for personal reasons, and some schools recently switched therapy providers. Nampa works with Terry Reilly, Tidwell Social Work and Pathways Idaho to provide the in-school counseling.

“The one criticism I have with Nampa High is that they keep constantly changing different programs,” said Charles Barber, a senior who has used the in-school counseling program for three years. “When you build up a relationship with one counselor and all of a sudden that person gets taken away for someone completely new…it’s going to be jarring to literally anyone.”

A successful in-school therapy partnership hinges on collaboration, said Melissa Mezo, Terry Reilly’s Behavioral Health director. Schools have to provide a space for their counselor, and help them find enough clients to fill their time.

“Everybody wants a school-based counselor, but not everybody understands the level of commitment that goes into helping that person,” Mezo said.

The in-school counseling is just one piece of a broader focus Nampa has put on mental health in the last several years. The district implemented a curriculum to teach students’ behavioral skills and is building social-emotional learning benchmarks into grade-level expectations. Teachers are being trained in trauma-informed practices.

“It’s not just about trying to manage kids, so that they can learn,” Endeavor Principal Heather Yarbrough said. “It’s about teaching those self-regulation skills so students can manage themselves.”

Families are seeing the growth.

When Aydin Lindholm got knocked down on the playground recently, he remembered to take a few deep breaths to calm his anger. And when the fourth-grader was feeling overwhelmed in class, he tried to find Forster during the school day, to ask if she had time to fit him into her schedule.

“I was really proud of him for being able to do that,” Stephanie said. “That’s not something I think he would have done on his own a couple of years ago.”

Read more in this series:

Sunday: Idaho’s approach to youth mental health was already scattered. Then COVID hit.

Monday: Calvin Loffer survived a suicide attempt. Now he has a message: Mental health can impact anyone.

Wednesday: Cassia County aims to connect students with immediate mental health services.

Thursday: How the Lapwai School District is leveraging relationships for mental health supports.