By the time Idaho students turn the tassels on their graduation caps, they should know about forced assimilation, boarding schools, treaties, and tribal sovereignty.

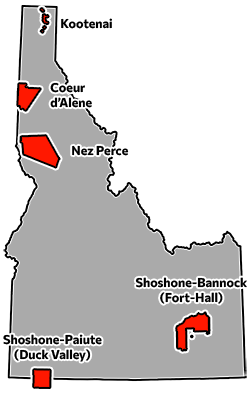

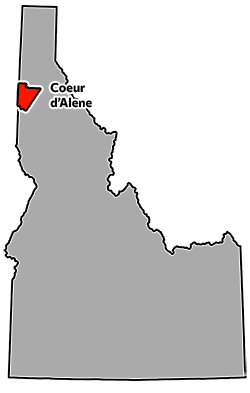

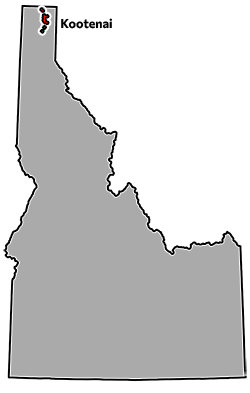

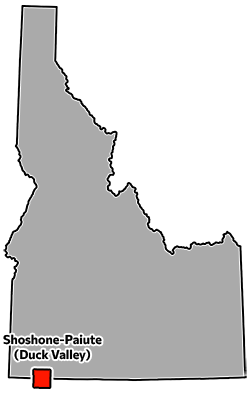

They should be able to name the five tribes that live in Idaho and dispel misconceptions about Native American people. And they should be well aware that Native Americans exist beyond the pages of history books.

Yet still today, Native Americans throughout the state experience vast ignorance from some non-Native people, who ask if they grew up with running water or live in teepees, or express surprise at meeting a Native person.

It sparks Indigenous communities to host powwows and field trips as a way to proclaim: ‘We are still here, and we are thriving.’

But it shouldn’t need saying.

“…Perhaps one of the grossest injustices to American Indian people, is the narrative passed down through generations of students that is myopically focused on the history or historical view of Indigenous peoples.” — Johanna Jones, coordinator of State Department of Education’s Indian Education department

According to Idaho’s content standards — a comprehensive list of what every student should learn in every subject and grade level — students should be learning about Native Americans throughout their days in public school, from kindergarten through high school.

But when asked about the Native American curriculum in their schools, many education leaders point only to fourth grade, when Idaho history is featured (including information on tribes living in the Gem state).

And it’s true that fourth graders are expected to learn more about Native Americans than at any other point in their K-12 career.

But education about Native Americans is supposed to start years before and continue long after those nine and 10-year-olds sit in their fourth grade classrooms. And it’s supposed to be more than a history lesson.

Students need to learn about “accurate historical AND contemporary aspects and perspectives of the five federally recognized tribes of Idaho,” Johanna Jones, coordinator of State Department of Education’s Indian Education department, wrote in an email.

“The most heard, and perhaps one of the grossest injustices to American Indian people, is the narrative passed down through generations of students that is myopically focused on the history or historical view of Indigenous peoples,” Jones wrote. “The very fact that this is a narrative that is still heard in classrooms today is why we collectively continue this critical work.”

Improving Idaho’s Native American curriculum hasn’t been easy — and there’s still work to do

For years, leaders in the Indian Education community — including Jones — have been striving to improve Idaho’s curriculum. But those efforts can stir controversy.

About eight years ago, the Indian Education Committee made recommendations for changes to Idaho’s social studies standards to improve the way teachers educate students about Native Americans. Eventually, many of those recommendations were accepted, “but not without a very arduous exchange of explaining and justifying” them, Jones wrote.

D’Lisa Penney, the principal at Lapwai Middle/High and a Nez Perce tribal member, said that she was involved in some of those past efforts to update Idaho’s social standards curriculum. At the time, one of the standards instructed teachers and students to celebrate Columbus Day.

“CE-LE-BRATE,” Penney said, incredulous and enunciating each syllable.

For Native American communities, Christopher Columbus symbolizes the beginning of centuries of oppression and is not a figure to revere.

Penney remembers representatives from various tribes advocating for improved standards and getting some pushback.

“It was a fight,” she said.

Some people said more robust standards about Native Americans were important for her school that served primarily Indigenous students.

“I said, ‘No, they’re more important for all the rest of you,” Penney recalled.

Eventually, the standards did get updated — but they’re still not perfect, Penney said.

And the work on them continues.

Every six years, Idaho’s content standards are reviewed and adopted. In 2022, a committee was meeting regularly to review the social studies standards. One of their focuses was on standards pertaining to American Indian education.

However, since Superintendent Debbie Critchfield stepped into office, progress has been paused. An April meeting was postponed to ensure that “continued work aligns with (Critchfield’s) vision,” according to an email sent to committee members.

Scott Graf, the SDE’s communications director, said the committee “is now being modified to include a broader stakeholder group that can incorporate and advance the work already completed.” The committee will likely meet again this summer.

For now, here’s what the standards say.

What Idaho kids should be learning about Native Americans, from kindergarten to graduation

This list was compiled from Idaho’s social studies standards. Standards pertaining to Native Americans are not present in any other content area.

K-4

While in these grades, students should:

- Build an understanding of the cultural and social development of the United States.

- Trace the role of migration and immigration of people in the development of the United States.

- Identify the sovereign status and role of American Indians in the development of the United States.

- Identify the sovereign status and role of American Indians in the development of the United States.

3rd Grade

By the end of grade three, students should be able to:

- Compare different cultural groups in the community, including their distinctive foods, clothing styles, and traditions.

- Identify and describe ways families, groups, tribes and communities influence the individual’s daily life and personal choices.

- Identify characteristics of different cultural groups in your community including American Indians.

4th grade

By the end of fourth grade, students should be able to:

- Analyze and describe the effects of westward expansion and subsequent federal policies on Idaho’s American Indian tribes.

- Identify the five federally recognized American Indian tribes in Idaho: Coeur d’Alene, Kootenai, Shoshone-Bannock, Nez Perce, and Shoshone-Paiute Tribes and current reservation lands.

- Discuss how Idaho’s tribes interacted with and impacted existing and newly arriving people.

- Identify and discuss similar and different key characteristics of American Indian tribes in Idaho.

- Compare and contrast past and current American Indian life in Idaho.

- Identify the meaning of tribal sovereignty and its relationship at the local, state, and federal levels of government.

- Describe the preservation of American Indian resources, including cultural materials, history, language, and culture.

- Identify and dispel misconceptions about American Indians today.

- Describe and analyze how American Indians and early settlers met their basic needs of food, shelter, and water.

- Discuss the governing structure of American Indian tribes in Idaho.

- Identify the diversity within Idaho’s American Indian tribes and develop an awareness of the shared experiences of indigenous populations in the world.

- Discuss the impact of colonization on American Indian tribal lands in Idaho, such as aboriginal and/or ceded territories, and the Treaties of 1855 and 1863.

5th grade

By the end of fifth grade, students should be able to:

- Discuss the American Indian groups encountered in western expansion.

- Discuss that American Indians were the first inhabitants of the United States.

- Identify examples of American Indian individual and collective contributions and influences in the development of the United States.

- Define the terms treaty, reservation, and sovereignty.

- Explain that reservations are lands that have been reserved by the tribes for their own use through treaties or executive orders and were not “given” to them. The principle that land should be acquired from the Indians only through their consent with treaties involved three assumptions:

- That both parties to treaties were sovereign powers.

- That Indian tribes had some form of transferable title to the land.

- That acquisition of Indian land was solely a government matter not to be left to individual colonists or to the States.

Grades 6-12

By the end of grades 6-12, students should be able to:

- Analyze the concept of Manifest Destiny and its impact on American Indians in the development of the United States.

- Trace federal policies and treaties such as removal, reservations, and allotment that have impacted American Indians historically and currently.

- Explain how and why events may be interpreted differently according to the points of view of participants and observers.

- Identify the impact termination practices such as removal policies, boarding schools, and forced assimilation had on American Indians.

Grades 9-12

By the end of grades 9-12, students should be able to:

- Trace federal policies, such as Indian citizenship, Indian Reorganization Act, Termination, AIM, and self-determination which have impacted American Indians historically and currently.

- Discuss the impact of forced assimilation on the land, cultural practices, and identity of American Indians.

- Identify and discuss the influences of American Indians on the history and culture of the United States.

- Analyze and explain sovereignty and the treaty/trust relationship the United States has with American Indian tribes with emphasis on Idaho, such as hunting and fishing rights, and land leasing.

- Explain the implications of dual citizenship with regard to American Indians.

*Editor’s note: In this story, the term “American Indians” was sometimes used to refer to Native American students in order to match the State Board and/or State Department of Education’s terminology.

This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.