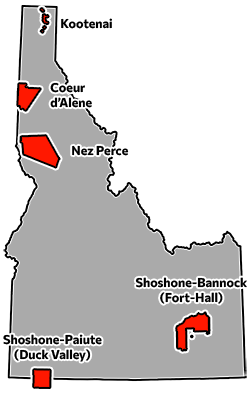

Idaho students are getting vastly different classroom experiences on Native American history and culture depending on where they live. And it’s led to serious consequences.

Creating a place for Native Americans in the classroom and incorporating more Indigenous voices benefits all students, Indigenous education leaders say, because:

- Tribal students feel proud and included when they see their culture and community members in schools.

- And non-Native students develop open-mindedness, unlearn harmful stereotypes, and gain a more complete understanding of the world and its people.

Plus, according to Idaho learning standards and goals, it’s more than a “should” — they’re required to.

Yet progress in Idaho public schools is all over the place.

Some are at the forefront, innovating new approaches so that Indigenous people and perspectives are frequently seen and heard.

Others lag far behind, with little more than a fourth-grade unit on tribes that may contain antiquated or erroneous information.

Native American students are among the state’s most vulnerable populations, repeatedly falling behind their peers. And non-Native students are still earning high school diplomas without a basic understanding of tribal communities — that they still exist, that they are sovereign nations, that forced removals, assimilation, and treaties impact them even today.

With no systemized approach and minimal oversight and accountability measures, it’s largely been up to districts and schools to prioritize Native American education — or not.

Even those schools in the heart of tribal communities are moving at different paces — Some are striding ahead in leaps and bounds, and others seem to be stuck in place.

But collectively, they provide a glimpse into the patchwork state of Native American education in Idaho. Here are their eight stories:

Southeast Idaho:

- Pocatello/Chubbuck: In a district with more Native American students than any other, a controversial mascot has been replaced. But there’s still work to do

- Blackfoot: Tired of being stereotyped and misunderstood, Native American teens are educating their peers

- Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High: School leaders want to help students cope with the lasting impacts of forced removals and boarding schools

- Chief Tahgee Academy: School leaders question metrics for success. Does the ISAT matter more than language, culture, and identity?

Northern Idaho:

- Plummer-Worley: A struggling district has a strained relationship with the local tribe

- Coeur d’Alene Tribal School: Tackling trauma and seeking teachers in the shadow of a boarding school

- Lapwai School District: An unusually strong relationship between the tribe and district has led to innovative approaches

- Boundary County: Few Native American students, and limited examples of Native American curriculum

Pocatello/Chubbuck: In a district with more Native American students than any other, a controversial mascot has been replaced. But there’s still work to do.

Most of the state’s Native American students attend school in the Pocatello/Chubbuck school district, where — just two years ago — education leaders retired a controversial mascot: the Indians.

Pocatello High students became the Thunder in 2021, ending decades of troubling practices at the school — like offensive cartoon caricatures of Native Americans in yearbooks and non-Native staff and students proclaiming: “I am an Indian.”

And the Pocatello High dance team — the Indianettes — used to don feather headdresses and take over the gym during halftime, performing a routine called the “Traditionals.” At some point, the headdresses were dropped, but an online video of the dance from 2015 shows dancers barefoot, wearing feathers and faux buckskin dresses, and carrying arrows. The dance was performed as recently as 2020.

But then Principal Lisa Delonas, a former Indianette herself, experienced what she called a ‘paradigm shift.’

“Over the years, as we have gained more cultural insight and sensitivity, listened to the voices of Native American individuals and organizations, and engaged in discussions with our local tribe, we have changed and discontinued practices that we learned were disrespectful, perpetuated negative stereotypes or misrepresented a group of people,” she wrote in in 2020 column for the Idaho State Journal. “It has taken us a long time, but we are finally listening to the voices that matter — the voices directly impacted by Native American mascots.”

“It has taken us a long time, but we are finally listening to the voices that matter — the voices directly impacted by Native American mascots.” — Lisa Delonas, Pocatello High Principal, wrote in 2020 about retiring the ‘Indians’ mascot

Pocatello High’s mascot change is one of a handful that have occurred in Idaho — including in Boise, in Teton, and in Nezperce.

Many Native Americans in Idaho breathed a sigh of relief at the changes.

Shawna Campbell-Daniels, a postdoctoral fellow and project director for the University of Idaho’s Indigenous Knowledge for Effective Educator Program, is one of them.

She said powwows are deeply meaningful ceremonies, steeped with regalia, history, tradition and intention. Native American youths become ashamed of their own culture when they see communities perform those ceremonies without properly understanding or valuing them.

“It’s like going to church and having communion,” she said. “And to have a group of people making fun of that is very hurtful … Negative representations like that actually impact Native identity and the way that they see themselves.”

But the Pocatello-Chubbuck district is ready to close that chapter of its past — now, the only powwow-type dances taking place are performed by Native American students, who understand their significance.

The district has also taken steps to incorporate more Native American voices into its curriculum. In 2020 and 2021, history teachers met to do just that.

Towersap remembers working with some of those teachers, and said she’ll never forget walking into a history classroom and immediately being surrounded by posters and images of historical figures — all of whom were white. She was shocked.

How would a Native student feel in the classroom? She wondered where the representations of Native Americans were and brought up her concerns.

“We had some really good conversations. The teachers were embarrassed when we started bringing up these issues, and they were very willing to rectify as many of the things as they could,” Towersap said.

And she remembers a meeting where she provided Pocatello teachers with ideas and resources for incorporating more Native American voices in the curriculum.

Afterward, a number of teachers came up with questions or comments, and expressed their fear of “getting in trouble” or facing pushback from parents for including Native American perspectives.

“So that was alarming,” Towersap said. “Because it’s not that we’re asking for any kind of slanted view on race or privilege … It’s not that we’re trying to change people’s beliefs. It’s just flat-out history.”

And Pocatello, which is located on lands that were part of the original Fort Hall Reservation, has been part of that history.

But Towersap said most of the teachers were receptive and open to “telling the whole story.” And the district did add more Native American perspectives to its social studies units.

Blackfoot: Tired of being stereotyped and misunderstood, Native American teens are educating their peers

In Blackfoot, Native American teens are frustrated with stereotypes and misinformation.

“A lot of people think Native Americans just exist in movies or books,” Josie Raya, a Blackfoot High student, said.

Even her teachers have shown ignorance — Raya remembers being taught a false ‘pilgrims and Indians narrative’ when growing up.

“I’ve known since I was a kid that the history taught in schools was wrong,” she said. “It felt like my culture and traditions were not shared enough or told accurately in the educational system.”

So she and fellow Indigenous peers decided to take matters into their own hands.

This spring, after finding out that many Blackfoot students had never been to the tribal museum or nearby reservation, they planned and hosted a fourth-grade field trip.

“We want to show our culture so they respect us more,” Student Dacree Coby said. “The more they know, the better.”

She hoped spending a day immersed in Shoshone-Bannock culture would make students pause before using offensive terms like “Indian” or making unfair assumptions about Native Americans.

But it’s not just the field trip. Blackfoot’s tribal students also organized a recent multi-day powwow, and are active in Indigenous Clubs on campus, which give students a place to belong.

Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High: School leaders want to help students cope with the lasting impacts of forced removals and boarding schools

At Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High, students speak what School Director Allen Mayo calls “rez English” — a byproduct of forced assimilation.

When Native American people were forced to abandon their own languages and adopt English, they retained the structures and frameworks of their own languages (Shoshoni and Bannock in this case), and subbed in English words. The result was a hybrid language distinct from foreign, academic English.

Language is one barrier to academic achievement that stems from the traumas of boarding schools. Another is chronic absenteeism — a resistance to and distrust of education can keep kids home from school.

“We’re trying to recognize it and not blame the kids for what happened in the past,” Mayo said.

And there’s generational trauma to account for: “A lot of our kids are being raised by their grandparents for one reason or another, either their parents died or were incarcerated or some other situation happened.”

The school offers cultural and Shoshoni language classes to connect with students’ identities, but even those are complicated by fraught histories.

Community members, for example, speak different dialects of Shoshoni, so it’s hard to reach a consensus about which version should be taught at school.

Towersap said that is a direct result of tribes’ forced removal from their homelands. The Fort Hall Reservation became the home to many different family bands from a number of areas across the county, each of which had its own version of the Shoshoni or Bannock language.

“We still suffer from the 150-year-old forced removals,” she said.

So there are obstacles. But Mayo has solutions in mind. Next year, he’s thinking about testing students to see if they qualify as English Language Learners. If so, the school could get more resources to help them.

And the school wants to focus on trauma-informed approaches to build relationships and project-based learning to engage students. Eventually, Mayo hopes the school can earn a STEM designation.

Chief Tahgee Academy: School leaders question metrics for success. Do ISAT scores matter more than language, culture, and identity?

Chief Tahgee Academy was identified as one of Idaho’s lowest performing schools this year, according to a ranking system created by the State Department of Education.

But Director Joel Weaver says the school is successful in ways that aren’t accounted for in the SDE’s metrics.

For example, the academy is producing new Shoshoni speakers and helping preserve an endangered language. School leaders are finding and hiring Native American teachers, and have eight full-time certified educators on staff, as well as three uncertified instructors.

And the school is centering Native American students’ identity rather than overlooking or stifling it.

“This is a school where the kids are very proud that they’re Native,” Weaver said. “We make every aspect of being a Shoshone-Bannock member really, really important.”

In April, the program garnered national recognition when Shelly Lowe, chair of the National Endowment for Humanities, visited the school.

She was in town to attend an Idaho Humanities Council event, and chose to visit Chief Tahgee academy in order “to reach communities we haven’t been reaching before.”

Lowe, the first Indigenous chair of the NEH, said the organization is working to support Native American language and cultural curriculum.

Her takeaway from visiting Chief Tahgee: “There’s a real commitment to preserving the language, and not just from the individuals and school system, but from the parents who have placed their children in the school.”

But the school also had some clear challenges to overcome, she said, like few comparable schools to network with and difficulty finding Shoshoni-speaking teachers.

“Supporting teachers and getting them into classrooms is a major barrier for a lot of schools and these immersion schools in particular.”

Plummer-Worley: A struggling district has a strained relationship with the local tribe

The Plummer-Worley school district’s three schools were ranked as some of the lowest-performing in the state in 2018 and 2022.

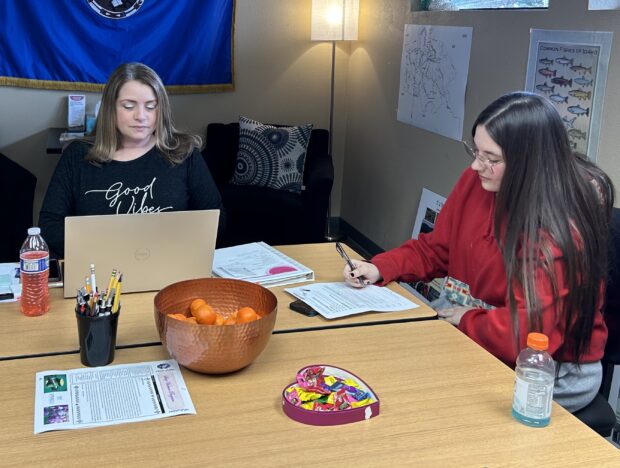

The news came as no surprise to Shaina Nomee, an instructor for the University of Idaho who teaches classes at Plummer-Worley’s Lakeside Jr./Sr. High as part of the Juntos extension program.

“We all kind of knew it was coming,” she said of the rankings. “We all need to take some time to really reflect on what we can do better to improve and grow.”

The Plummer-Worley schools are located just blocks away from the Coeur d’Alene tribe’s Department of Education, but the tribes and district operate as separate entities — the product of a relationship that’s frayed over the years.

Leaders with both the district and the tribe don’t want the relationship to unravel any more than it has. But it seems it will take some time to rebuild what’s been undone.

For now, the tribe takes student learning into its own hands in as many ways as possible — offering after-school tutoring, summer enrichment programs, and cultural training for local teachers.

Dr. Chris Meyer, director of education for the Coeur d’Alene tribe, said these programs and others aim to fill educational gaps for Coeur d’Alene students.

“It gives them voice because our history is omitted from textbooks,” she said. “So we want to give them that knowledge about their history. And we want them to resist in healthy ways, and you can only do that if you have knowledge.”

Nomee is a member of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and her husband and children are Coeur d’Alene tribal members. She’s lived on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation since 2003, and is “invested in the community.” Her own children are students in the district and with some supplemental programming — including that offered by the tribe — she feels they’ve gotten a good education.

But the district has plenty to work on.

Absenteeism has been a major issue, and schools could do more to engage with families and the community.

Plus, there are not many Native American teachers like herself.

“Our teachers and our leadership here in the Plummer-Worley School District are not representative of our community at all, which is unfortunate,” she said. “Representation matters, whether everybody wants to believe it or not.”

Nomee wants to be part of the solution. She teaches classes three days a week, including a STEAM class, an academic success class, and a 4H class — all part of a U of I extension program, which is new to the district this year.

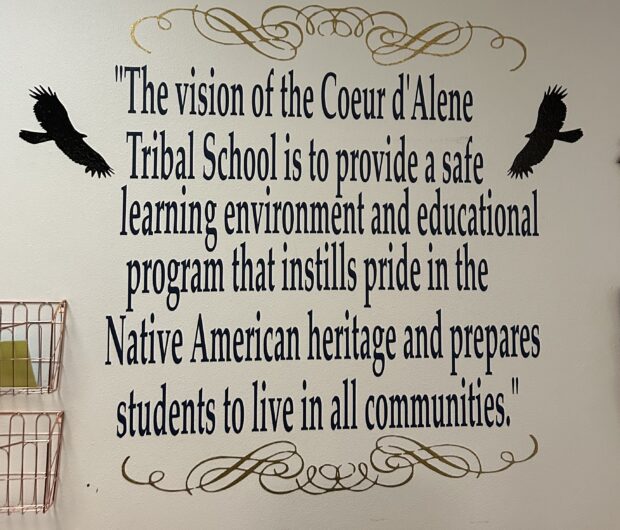

Coeur d’Alene Tribal School: Tackling trauma and seeking teachers in the shadow of a boarding school

The small community of De Smet was once home to one of Idaho’s six federal Native American boarding schools.

The hilltop where the school used to sit is now just a parking lot and some informational signs. And at the base of the hill is the Coeur d’Alene Tribal School, one of Idaho’s two Bureau of Indian Education schools.

In the shadow of a complicated history, the tribal school is trying to write a new chapter of Native American education.

At this school, the Coeur d’Alene language is encouraged and taught rather than condemned. And the approximately 100 students who attend the K-8 school, and are all Native American, see their identities celebrated rather than rejected.

The school offers cultural events and activities, like canoe making, antelope runs, and salmon releases. Educators at the school have also worked to build strong relationships with students, and have adopted a trauma-informed approach to teaching.

“Our approach is not punishing kids, but ‘how can we help you grow in this area?’” Principal Tina Strong said. “It’s important for educators to recognize that not all kids that walk through the door come from a traditional family setting, so why are we casting blame on students that have not been taught these skills?”

Carrington Casaus, a registrar at the school, said that efforts to build relationships with kids are what set the school apart; the staff works to make it a place where students feel seen, heard, and loved.

But the school has been struggling to find and retain teachers — especially Native American teachers. For now, an unfilled vacancy means the principal has a class to teach every afternoon.

Lapwai School District: An unusually strong relationship between the tribe and district has led to innovative approaches

In Lapwai, district leaders have an especially close relationship with the Nez Perce tribe.

Superintendent David Aiken regularly reports to the Nez Perce Tribe Circle of Elders, who have “adopted” him, dubbing him an honorary member of the tribe.

There’s also a formal partnership between the entities — the Nez Perce State Tribal Education Partnership (STEP) — that has led to a number of initiatives:

-

- Cultural training for staff: The tribe’s STEP program offers a college credit course for local teachers, administrators, and counselors called “Indigenous Principles of Pedagogy.” It focuses on culturally-relevant teaching techniques for K-12 students.

- Native culture and language teams: The STEP program has developed these groups of staff, parents, and community members who work to infuse culture and language into the curriculum.

- Indigenous role models: The middle-high school team has created resources, available on the district website, that highlight the accomplishments of successful Indigenous role models.

- Annual community event: Each year, this event introduces parents to all the programs the district, tribe, and community offer for students.

- ‘Respecting our Elders’ day: Every spring, the tribal elders provide a presentation for students on “everything from language to what it means to be respectful, responsible, and safe.”

- Annual powwow: This spring event is held to honor retirees and graduating seniors.

The district also has its own Indian Education Department, which is unheard of in most schools.

“My goal and my job every single day is to empower our kids,” Iris Chimburas, director of the department, said. “Our job is to open up the doors for our kids.”

If teachers new to the district need help linking culture into a lesson about math or science, Chimburas and her team send resources their way.

“I think everybody, not just people of color, need to decolonize their mindset,” D’Lisa Penney said, adding that teachers need to be able to “take a curriculum and deconstruct and reconstruct it from the perspective of our students.”

Major textbook companies produce curriculum that is “not culturally responsive,” so the district encourages teachers to supplement those resources. And sometimes, that means letting students become the experts.

“The kids will Indigenize (the curriculum) for you if you give them the opportunity,” said Penney, principal of Lapwai Middle/High.

About 7 teachers out of 40 in Lapwai (or about 17%) are Native American, and the district is working to get more in the classroom with its teacher-track career program designed for high school students. And the district hopes to partner with the University of Idaho’s Indigenous Knowledge for Effective Education Program to get more of its existing Native American teachers into education leadership roles as principals or superintendents. Currently, Penney is one of just a handful in the state.

The district also offers Nez Perce language instruction and a number of Native American electives, including:

- Native American Arts (grades 8-12)

- Native American History and Research (grades 11-12)

- Native American Literature dual credit course (grades 9-12)

- Introduction to Cultural Sovereignty dual credit course (offered through a partnership with Northwest Indian College) (grades 9-12)

- Native Health And Wellness (offered through a partnership with Northwest Indian College) (grades 9-12)

- Powwow Dancing (offered through a partnership with Northwest Indian College) (grades 9-12)

And recently, the tribe and district collaborated on a two-day youth leadership event for Native American students — one day for girls and one day for boys. The students participated in traditional activities and mini breakout sessions with area leaders, and listened to speeches from two successful local Native Americans.

Chimburas said the ultimate goal of student programming is to help them lead happy, healthy lives, and prepare them to give back to the community and “(create) pathways for the next generation.”

Boundary County: Few Native American students, and limited examples of Native American curriculum

Just miles from the Canadian border, a small reservation is home to the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho.

It’s a small community, with a few tribal offices, a fish hatchery, and some homes.

The Idaho branch of the tribe (there are other bands living in British Columbia and Montana) claims only about 169 members.

And the local Boundary County school district only has about 37 Native American students, who comprise about 2.6% of its population.

Jennifer Porter, chairperson of the tribe, declined multiple requests for an interview, citing the impacts of the pandemic and ongoing efforts to recover as a community.

Jan Bayer, superintendent of the district, said she is hoping to connect with the tribe soon to establish a memorandum of understanding.

She and others at the district are interested in offering more Native American perspectives in the curriculum, but for now, it’s primarily limited to what’s taught in fourth grade Idaho history classes.

The textbook teachers use contain some information about local tribes that is both historical and modern, though there’s often not enough time to get to the contemporary material.

And the tribe has a liaison who supports support Native American students in the classroom by providing extra help and one-on-one instruction. The liaison also offers evening tutoring services for Kootenai students.

Otherwise, the district’s Native American curriculum and offerings are limited.

From Pocatello to Bonners Ferry, Idaho’s students have vastly different exposure to Native American voices. In a state where teachers once deliberately stifled Native American culture and identities, Idaho tribes are still fighting to be seen in classrooms.

This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.