At Blackfoot High, a student recently made fry bread for her classmates, and another shared a creation story that had been passed down from elders.

A few days before, students at Chief Tahgee Elementary Academy introduced themselves and recited colors and numbers in Shoshoni.

That morning at Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High, students listened as their teacher shared how treaties personally impacted Native American people — the restricted hunting that led to commodity canned food that led to heart disease and other health problems.

And a few months earlier, students researched different tribes and created dioramas showing their traditional homes and lifestyles at Blackfoot’s Independence High.

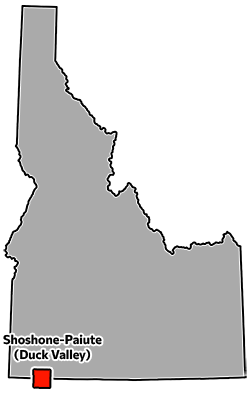

These schools — a traditional school, a charter school, a tribally-run school, and an alternative school — are all within miles of each other. And all are in Southeast Idaho, where the state’s largest concentration of Native American students live and learn.

In every case, these students were benefiting from the knowledge of Indigenous teachers.

They’re lucky — across the state’s public schools, there are only 56 Native American teachers, making up just 0.3% of all teachers.

Idaho’s top education leaders, from the state superintendent to State Board trustees, have called for more Native American educators, and there are ongoing efforts to make that happen.

The University of Idaho has a groundbreaking Native American educator program; the Lapwai School District has developed a future educator track for its primarily Native American student body; and grow-your-own initiatives are turning paraprofessionals into teachers.

For now, Idaho’s scant Native American teachers are a small but important bridge between cultures, providing an insight and perspective into history, culture, and language that only they can offer.

Here’s a peek into some of those educators’ classrooms.

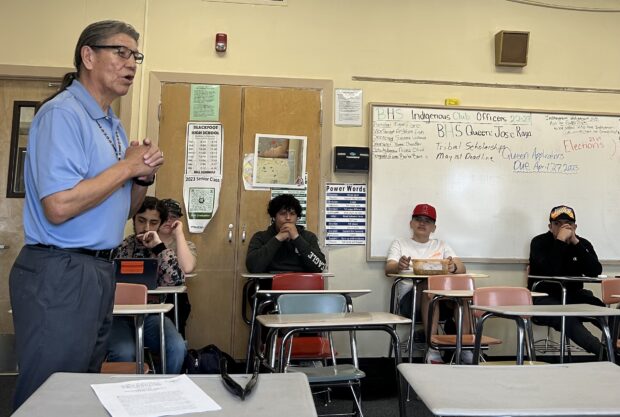

- First Period: Native American Culture with Merle Smith, Blackfoot High

- Second Period: Shoshoni Language with RJ Kutch, Chief Tahgee Academy

- Third Period: Tribal Government with Leah Pandoah, Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr High

- Fourth Period: Tribal Culture with Parvaneh Christensen, Independence High

First Period: Native American Culture with Merle Smith, Blackfoot High

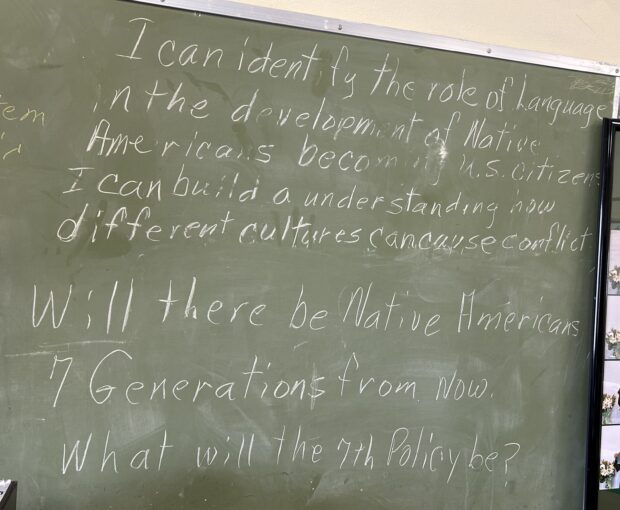

Will there be Native Americans seven generations from now?

The question, scrawled across the chalkboard, stood before Merle Smith’s students.

It depends, Smith seemed to be telling students. It depends on whether culture and traditions — like storytelling, and wearing long hair, and grieving the loss of a loved one for a year — can be preserved and honored.

And that’s the point of his class — to celebrate and perpetuate all that defines Native Americans.

On a recent Thursday, after listening to a lecture, Smith’s students were devouring homemade fry bread made by one of their peers.

As they ate, Smith reminded them of cultural practices: “We always share with guests and elders first,” he said, taking a piece himself. “And it’s rude not to at least try what someone’s made for you.”

Smith has been teaching at Blackfoot High for some 30 years, and he’s become an icon at the school.

Sporting a long ponytail and beaded lanyard, he often drifts into tangents as he teaches — but these digressions have lessons. He talks about how “Indian names” give direction, how Native Americans live in two worlds as citizens of their tribal nations and of the United States, and about an upcoming powwow that some of his students are hosting.

He invites students to share their stories, too. On this Thursday, a former student, JennaVecia Stagner, visited to share an oral history she learned from elders — a creation story.

“People like that are my hope,” Smith said after she spoke.

When the bell rings and class ends, it’s clear that Smith’s classroom is a home away from home for Native American students. Even though it’s lunch time, many students stay and eat their lunches. Others arrive from the hallways. It’s a gathering place.

It’s also where the school’s Indigenous Club meets. On those days, there’s not a seat left in the room.

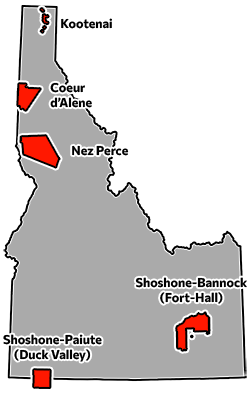

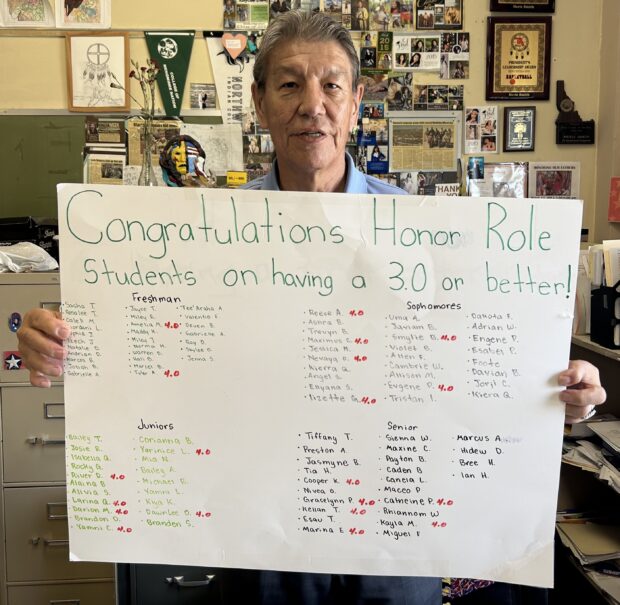

The walls of the classroom are bedecked with maps of tribal territories and Native American art. The names of Indigenous Club officers are proudly written out on Smith’s whiteboard. And a list of all the Native American students on honor roll are displayed on a poster board.

Smith said his teaching career started with a question: “Where could I reach the most Native American students and do the best job?”

For him, the answer has been Blackfoot High.

Many students there don’t know as much about their culture and language as they’d like, which Smith said circles back to boarding schools, where older generations were forced to assimilate and abandon their own ways.

“These kids are hungry to learn about their own culture,” he said.

Josie Raya, a Blackfoot High student, said having Smith as a teacher meant a lot to her. In his class, she learned about the sun dance, tribal treaties, the medicine wheel, and “Indian names.”

“He’s someone Native students can talk to,” Reyes said. “He’s like our family. I have a lot of respect for him.”

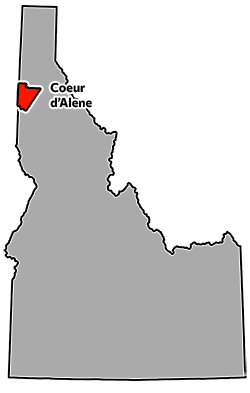

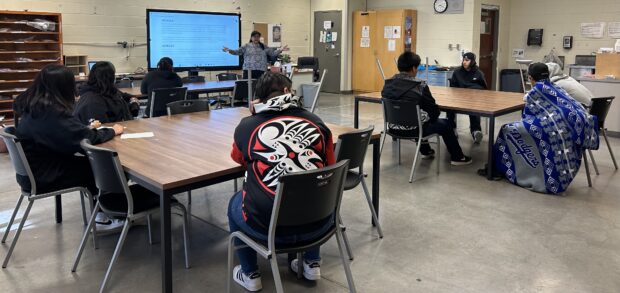

Second Period: Shoshoni Language with RJ Kutch, Chief Tahgee Academy

RJ Kutch started out as a custodian at Chief Tahgee Elementary Academy, a charter school located on the Fort Hall reservation.

Then, he got an offer: to learn Shoshoni from the school’s language teacher, Merlin Study, who is a rare fluent speaker.

Kutch jumped at the offer — as a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member, he’d been wanting to learn the language for years.

He now speaks at an intermediate level, has stepped into the classroom and is teaching students in the school’s dual immersion track. His wife, Le-Dein Kutch, has followed suit, and has started teaching this year as well.

The Kutchs don’t have their teaching certificates, so support the classroom teachers by offering language instruction.

Joel Weaver, the school’s director, is proud of the many Native American staffers at Chief Tahgee. The academy is a K-7 school that serves a 100% Native American population.

Most of the school’s teachers (eight full-time and one part-time) are Native Americans. And that’s not counting the three uncertified instructors (all Native Americans) who teach in the immersion program.

Principal Cyd Crue, who is not a tribal member but has deep roots and connections in the community, has played a major part in that by recruiting locals she sees potential in.

Together, those teachers help imbue the school with culture, language and tradition — which is an important part of the charter school’s mission. And they act as role models.

“It’s good for Native kids to see Native people succeed,” Crue said.

In Kutch’s class, beginning and intermediate students can understand directions in Shoshoni and respond, they can introduce themselves (in the traditional way, in which family members are listed before saying their own names), and they can recite colors and numbers.

“It’s not just a language, it’s not just words,” Kutch said. “There are feelings that go with those words, and to be able to learn that and that connection with our way of life is very important.”

Each year, he is pushing kids to advance their understanding in the hopes that someday, they’ll be among the speakers keeping the language alive. And to know he could have a small part in that means everything.

“I’m blessed to be able to do it,” Kutch said.

In the short clip below, Kutch’s students practice counting in Shoshoni.

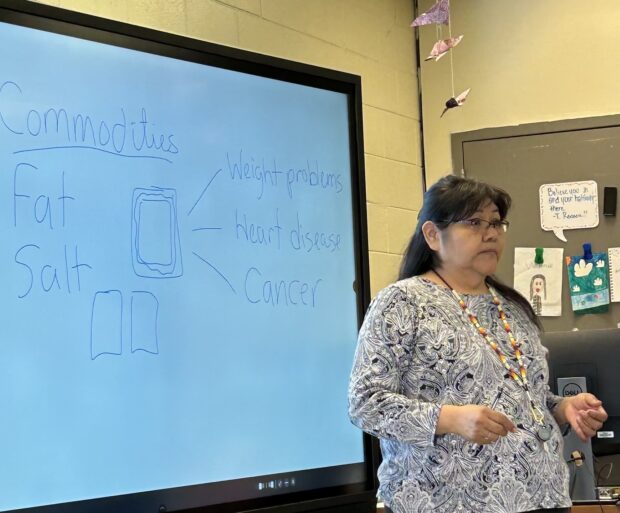

Third Period: Tribal Government with Leah Pandoah, Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr High

There are the dry, written historical accounts of treaties — agreements tribes made, often when under duress, that often resulted in forfeiting their land to the United States in exchange for certain services or rights.

And then there are the lived experiences and personal stories of what those treaties meant for Native American people.

In Leah Pandoah’s tribal government class, students get both versions.

Treaties meant tribes could no longer hunt — their traditional hunting grounds were no longer theirs to roam. The U.S. government aimed to keep Native American people bound to the confines of reservations so incoming settlers could move into the surrounding areas.

But the loss of hunting had serious implications, Pandoah told her students recently.

For one, men lost their purpose.

“We had a dysfunction occur that affected everything and that led to substance abuse and neglect,” Pandoah said. “We don’t always read it in the paper because nobody wants to talk about it here, but we know it exists.”

And the wild game that comprised the tribes’ diet was exchanged for “commodities” — government food rations that were often of substandard quality. Pandoah told stories of train cars full of rotting meat that had to be accepted as part of the treaty.

And there were the canned goods, packed with fat and salt, that would lead to health problems like heart disease and cancer.

In addition to tribal government, Pandoah also teaches the Shoshoni language and cultural arts. In every class, she embeds the cultural knowledge she carries as a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member.

She teaches her students about the tribal significance of colors and seasons, and she encourages them to learn as many Shoshoni words as possible. That week, her students’ assignment was to go home and label common, everyday items with a sticky note showcasing the Shoshoni word for it.

In that way, students would become teachers to their parents and families.

Pandoah grew up with Shoshoni as a first language, but lost her fluency when she entered the school system, where most spoke English.

“I just wasn’t hearing it enough,” she said.

When her mother passed away from cancer, Pandoah mourned the loss of her loved one and of the family’s last fluent Shoshoni speaker.

“I realized I had a real big task to try to capture my language back, so being in here helps me keep that alive,” she said.

Pandoah’s mother also inspired her to become a teacher. She’d gone to college at 35 to get her teaching degree, but ended up passing away before she could begin her career. So Pandoah decided to pick up where her mother left off.

Pandoah is well aware that she’s among the state’s few Native American educators. She said the low pay is a deterrent for many, as well as the dearth of educator preparation programs geared toward Native Americans. Plus, the types of classes she teaches (that would appeal to and play to the strengths of Native American teachers) aren’t offered at many schools.

But she hopes to see that change, and to see more people like herself in classrooms.

Fourth Period: Tribal Culture with Parvaneh Christensen, Independence High

Sometimes, it seems like there’s an invisible wall between the Fort Hall reservation and neighboring towns like Blackfoot and Pocatello.

“Nobody really knows what’s going on out here,” Cyd Crue, the principal at Chief Tahgee Academy Elementary, said recently.

And that intangible barrier breeds misunderstandings.

Parvaneh Christensen, a teacher at Blackfoot’s Independence High, an alternative secondary school, sees it all the time.

Christensen, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member, teaches tribal history and tribal culture and said her non-Native students know little about the Native Americans who live in their town, or just miles away on the reservation.

To some of them, the reservation is a scary place known for its wild dog packs, a place where they wouldn’t want to run out of gas. They assume people there live in teepees.

In class, Native American students and their non-Native peers openly discuss these stereotypes and break down myths: The reservation is no more dangerous than Blackfoot or Pocatello, and the stray dogs are often dumped there by those in surrounding towns. And Fort Hall residents live in modern-day houses just like anyone else.

By the end of Christensen’s tribal culture class, all students come away much more knowledgeable and learn about various tribes and their distinctions. And the Native American students get to become the experts, sharing part of their traditions and heritage.

“That culture sharing is important, because it’s a way for us to show that we’re here, we’re alive, we’re still practicing this culture,” Christensen said.

Too often, Native American people are only portrayed as historical figures in textbooks, not living, breathing people — and certainly not as the person sitting in the next row.

In class, her Native American students get to showcase their beadworking abilities or wear their ribbon skirts to display their heritage. Their culture is celebrated.

“It’s really important that we get our Native American youth to realize that they’re part of something bigger than themselves,” Christensen said. “They come from resilient people. They come from ancestors who have faced everything.”

Christensen said she never planned to become a teacher; the Blackfoot School District reached out and recruited her into the role. But now that she is, she sees teaching as an honor — a chance to be a small but important influence on each student’s life.

“I don’t feel like my students are blessed because they have me,” she said. “I’m truly the blessed one in this situation.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.

This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.