Editor’s note: This story is the first in a series about Native American education in Idaho. In coming days, look for more stories on efforts to increase the number of Native American teachers in the classroom, and to incorporate more Native American perspectives and voices in the curriculum.

Sometimes, classrooms are more potent weapons than war.

That, at least, was the U.S. government’s conclusion when it came to oppressing Native American people: boarding schools were the battlefields, nuns and teachers the soldiers, and Native American children the enemy.

The details of what life was like within Native American boarding schools — where children were severed from their families, language, culture — have often died with the last survivors. They were memories tribal members did not want to dredge up, a story they left untold.

Yet in spite of those silent elders, the troubling legacy of boarding schools still haunts Native American communities in Idaho and across the country.

It lives on in the loss of language after kids were punished for speaking their native tongue, and in the fractured families reeling from decades of generational trauma. It’s evidenced in the forgotten traditions now lost to time, and in intentional attempts to erase Native Americans. It’s there in non-Native people’s surprise when they find out that tribes were not wiped out but still thrive.

These outcomes were intentional.

The U.S. government admitted as much in an investigation of boarding schools released last year under the direction of Deb Haaland, the country’s first Native American leader of the Department of the Interior.

Education was the gilding that masked the schools’ true purpose: to weaken tribal communities and take their land, according to the report.

The United States government aimed to break what made these communities strong: family ties, a migrant way of life, language, culture, and tradition. In doing so, they could essentially corner tribes until they were forced to give up their land.

“It is cheaper to educate our wards than make war on them,” the commissioner of Indian affairs wrote in an 1886 annual report to the U.S. interior secretary.

“It is cheaper to educate our wards than make war on them,” the commissioner of Indian affairs wrote in an 1886 annual report to the U.S. interior secretary.

Plus, educating children could be sold as charitable — Christian, even. In fact, many boarding schools were run by nuns, missionaries, and church officials, some of whom lacked the disposition or education necessary to teach.

Under the guise of goodwill, schools became a military tool to oppress a perceived enemy, and self-sustaining labor camps where Native Americans were forced to work and pay for their own subjugation.

Likely tens of thousands of children died at these schools due to malnourishment, harsh conditions, and disease. They are buried in unmarked graves, a number of which are still undiscovered.

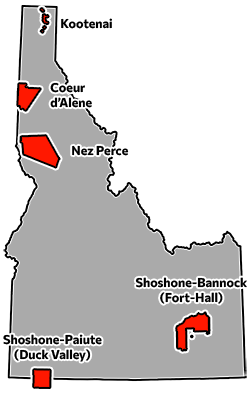

Idaho has its own chapter in this grim account.

Here, there were six government-run boarding schools, and more that were independently run by churches and other organizations.

Whatever Idaho town you live in, the site of one of these schools is not far away. In the places where Idaho’s Native American boarding schools once stood, there are now vacant lots, crumbling buildings, or sometimes a sparsely-worded memorial. You may have driven right past one, oblivious.

But national and statewide efforts are underway to unearth this buried history and learn from the past.

And Idaho schools — the very roots of this trauma — are sometimes becoming the salve, especially when their leaders are Native Americans or link arms with local tribes.

A groundbreaking report on Federal Indian Boarding Schools

THE TIMELINE:

—In March 2021, Deb Haaland made history, becoming the first Native American to serve as the U.S. secretary of the interior. Haaland is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and a 35th generation New Mexican.

—In June 2021, Haaland announced the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative, a comprehensive review of the troubled legacy of federal boarding school policies. The effort is the first-ever inventory of federally operated Indian boarding schools.

—In May 2022, Haaland and Bryan Newland, the assistant secretary for Indian Affairs, released the first volume of an investigative report into federal Indian boarding schools.

—Volume 2 is expected to be published by the end of 2023.

Between 1819 and 1969, the United States government “coerced, induced, or compelled” Native American children to attend its boarding schools, which eventually grew to more than 400 across 37 states.

The families and children were not always willing.

“Some hurried their children off to the mountains or hid them away in camp, and the Indian police had to chase and capture them like so many wild rabbits,” U.S. Indian Agent Fletcher J. Cowart wrote of an 1886 effort to force Mescalero and Jicarilla Apache children to attend boarding schools.

Valerie Miller, a teacher at Swan Falls High in Kuna, said her grandfather attended a boarding school in Minnesota and escaped three times by hitchhiking and walking home. They caught him twice, but the third time “they didn’t make him go back.”

Miller, a Stockbridge-Munsee Mohican tribal member, said others have stories like hers — of “aunties and uncles hiding under their beds,” to keep from being forced to go to a boarding school.

“These stories are within living memory,” she said.

There was a reason those children fled, hid, and escaped.

At these schools, children were renamed, their hair was cut, and their language and culture were forbidden. And half of each day was often spent doing manual labor that would have violated many states’ child labor laws.

The goals of these duties — which included ranching, farming, brick-making, garment-making, and blacksmithing — were twofold: 1) to make the boarding schools cheap and self-sustaining as children made their own food and clothes and did their own washing and cleaning; and, 2) to train the children in “employment options often irrelevant to the industrial U.S. economy,” and thereby limit their success as adults.

Young children performed heavy labor while being underfed and neglected. Malnourishment, disease, overcrowding, and inadequate health care plagued these schools, and physical, sexual, and emotional abuse were rampant.

On top of that, children were often flogged, whipped, slapped, and cuffed as punishment.

Somewhere between thousands and tens of thousands of children died; the number is an estimate because their graves are still being discovered.

In a report that was released last year — the first of its kind and an effort to acknowledge part of America’s troubled history — the Department of the Interior acknowledged 53 boarding school burial sites and said it expects many more to be discovered.

Those who survived were more likely to have a number of diseases later in life, including cancer, tuberculosis, high cholesterol, diabetes, anemia, arthritis, and gall bladder disease.

Then there was the mental toll. Survivors were also more likely to develop PTSD, depression, and “unresolved grief.” Many experienced a “prevailing sense of despair, loneliness, and isolation from family and community,” according to the report.

Men, who were more likely to have been physically and sexually abused in the schools, faced increased trauma and stress, which then impacted them physically. These stressors may even have been passed down to their children — a phenomenon known as epigenetic inheritance.

In this way and in others, the devastating impacts also reached into the lives of those who never stepped foot in these schools.

Survivors often didn’t share their stories, but the trauma trickled down anyway

The grandkids of those who once attended the now-infamous Native American boarding schools mostly remember silence when the topic arose.

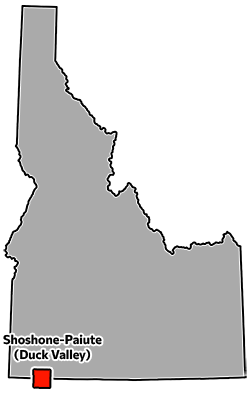

Dana Hernandez’ grandmother attended an all-girls boarding school, though Hernandez, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member, doesn’t know which one.

“She was forced to go there … she hated it,” Hernandez said. “(The students) were paddled and forced to do hard labor, and she didn’t like that.”

Beyond those painful fragments, Hernandez doesn’t know much else about her grandmother’s experiences, which she was reluctant to divulge.

Yvette Towersap’s grandmother was similarly reticent. She was forced to go into a boarding school when she was six, and didn’t return home until she was 18.

Towersap doesn’t remember her grandmother ever talking about the boarding school (and she was also very young when her grandmother was alive), but she still saw its impacts. Her parents, for example, didn’t teach her the Shoshoni or Bannock languages that they knew, because they felt it would be better for Towersap to learn English — that way she could avoid being singled out like the past few generations had been.

“To me, that’s one of the biggest, strongest indicators of boarding schools,” Towersap said. “Language is one of the strongest indicators of our identity. And so (boarding schools were) very effective in terms of severing that family and cultural tie.”

In fact, that was one of the U.S. government’s main goals — to break down families and weaken the Indigenous people seen as enemies, then take their land. And all of this could be done without wars.

Weaponizing classrooms: When education becomes more effective than war

Federal Native American boarding schools “were designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people,” the report read.

By making parents and children strangers to each other, the government hoped the children would “be absorbed one by one into the white population.”

And these dubious goals were first sowed by America’s founding fathers, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, according to the report.

Assimilating Native American children was considered “the cheapest and safest way of subduing the Indians, of providing a safe habitat for the country’s white inhabitants, and helping the whites acquire desirable land, and of changing the Indian’s economy so that he would be content with less land. Education was a weapon by which these goals could be accomplished,” the report reads.

The government realized that by transforming Native Americans’ way of life from nomadic and hunting-based to one that was stationary and agriculture-based, the tribes could be confined to smaller parcels of land.

“The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them,” Thomas Jefferson, who was president at the time, wrote in an 1803 confidential message to congress on Indian policy.

And changing their lifestyle would require the tribes to purchase and obtain new items and equipment that they did not need before. The government encouraged tribes to make purchases on credit so they would fall into debt. That debt could then be used as leverage to get tribes to sign treaties — which was often done under duress — and give up their land.

Proceeds from the newly acquired land would then help pay for any costs the boarding schools incurred on the federal government.

Ultimately, tribes ended up paying for and supplying the labor for the subjugation their children faced in these classrooms.

“As a result, the United States’ assimilation policy, the Federal Indian boarding school system, and the effort to acquire Indian territories are connected,” the report read.

Indian boarding schools “go further … towards securing [U.S.] borders from bloodshed, and keeping peace among the Indians themselves, and attaching them to us, than would the physical force of our Army.” — U.S. Department of the Interior

As the government commissioner bluntly put it: “Past experience goes far to prove that it is cheaper to educate our wards than to make war on them …”

The Department of the Interior reached similar conclusions: Indian boarding schools “go further … towards securing [U.S.] borders from bloodshed, and keeping peace among the Indians themselves, and attaching them to us, than would the physical force of our Army.”

While the clear purpose of the schools was to oppress, weaken, and take advantage of tribes, the ostensible purpose was painted more favorably: to educate Native American youth.

It was a mission that religious leaders were drawn to, and in many cases, churches took over the daily operations of the boarding schools in the government’s stead.

Most boarding schools started as day schools, which were “established through the benevolent efforts of missionaries or the wives of Army officers stationed at military reservations in the Indian [C]ountry.”

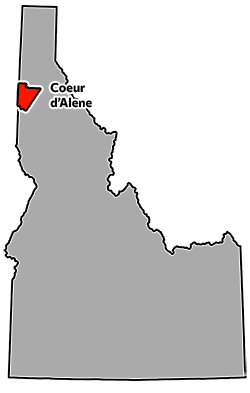

Among those “benevolent efforts” was the DeSmet boarding school, run by Catholic nuns on the Coeur d’Alene reservation.

Idaho’s DeSmet Boarding School: A source of pride and trauma

Atop a hill in DeSmet, a parking lot and some historical signs are all that remain of the boarding school, convent, and hospital that long stood there.

Overseen by Catholic nuns known as “the sisters,” the school included a dairy farm with poultry houses and extensive gardens. Children would spend afternoons doing manual labor, like picking potatoes and cabbages.

The sisters also converted the children to Catholicism and worked to assimilate them (historical photos show the students in neat lines with shorn hair and Caucasian clothing styles). And they were often successful.

“My great grandma didn’t speak Coeur d’Alene, she didn’t dance, she was a very devout Catholic because of (the school),” said Carrington Casaus, the registrar at the Coeur d’Alene Tribal School and a Coeur d’Alene tribal member.

“Some would say the Jesuits in the boarding schools did a very good job at what they were trying to do, and we’re still feeling the effects of that,” said Sean Burk, a counselor at the school, which is located just down the hill from the historical site.

But there are “two narratives” about the school, Burk said. For some survivors, the memories they formed there were too traumatic to retell. But others spoke fondly of their time at the school, and their ancestors are still devout Catholics today.

Perhaps the polarized opinions of the school are because some only attended the day school, and others lived there — the latter may have had more negative experiences.

Whatever the reason, the divided stance when it comes to boarding schools seems to be common.

Towersap, a policy analyst for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, said boarding schools have a long and complicated history. There were multiple on the Fort Hall Reservation alone, one of which was government-run, and others that were established separately by missionaries or churches.

Because of the variety of schools, there are also many differing opinions on them, she said.

For example, some former students were grateful for what they saw as hands-on, real-life training, while others considered that to be forced child labor.

“It depends on who you talk to, you get different perspectives,” Towersap said. “Boarding schools are a much broader and way more complicated time in our history (than people realize).”

To further entangle the matter, some Native American boarding schools still exist today and have reimagined themselves. They have become opportunities for tribal youth to “escape” their reservation, travel, and experience living as an adult.

Hernandez, whose grandmother hated boarding school, was one of those youths.

By her mother’s generation, the remaining government-run boarding schools had changed, and her mother had loved her experience. So Hernandez followed suit and moved from Fort Hall to Riverside, Calif., to attend Sherman Indian High.

“It’s basically like a college experience but for high schoolers,” she said.

Shelly Lowe, a Navajo tribal member and Chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, said, “a lot of different aspects … play into whether or not a student had a positive or negative experience.”

And her agency is ready to listen to all the viewpoints.

The ‘Road to Healing:’ New partnership seeks to gather and preserve boarding school histories

Last month, the NEH and Interior Department announced that they are working together to record and preserve oral histories about boarding schools and to digitize records documenting the experiences of survivors and descendants of federal boarding schools.

The goals: “to recognize the troubled legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies;” address their “intergenerational impact;” and “(shed) light on the traumas of the past.”

“I’m determined to use my position to help communities heal,” Haaland said. “This is one step, among many, that we will take to strengthen and rebuild the bonds with Native communities that federal Indian boarding school policies set out to break.”

It’s the first time the U.S. government has attempted to create a permanent oral history program on boarding schools, a resource requested by Indigenous communities — and it took a Native American secretary of the interior to make it happen.

As part of those efforts, Haaland is traveling the country on a “Road to Healing” tour, which aims to give Indigenous survivors the opportunity to share their stories. Lowe has already joined Haaland on several of those stops.

So far, there have been mixed reactions to calls for oral histories, Lowe said. Many are not ready to talk. Others are more willing, but it’s difficult for them to do so.

Lowe often points survivors to the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, based in Minneapolis, which offers support and resources.

“I’m determined to use my position to help communities heal. This is one step, among many, that we will take to strengthen and rebuild the bonds with Native communities that federal Indian boarding school policies set out to break.” — Deb Haaland, U.S. interior secretary

“(The history) is something that we need to understand to move forward towards building and strengthening tribal nations, to helping them meet the challenges they have today, and to move forward in the best possible way culturally, and to ensure that we as American people have a full understanding of our own history,” Lowe said.

Can schools transition from sites of trauma to springboards for opportunity?

Miller, whose grandfather ran away from boarding school three times, said that as a teacher at Swan Falls High, her relationship with education is positive. But it’s not that way for everyone.

“Many Natives do have a pretty significant distrust of any of those systems — both public schools and bureaucracies,” she said.

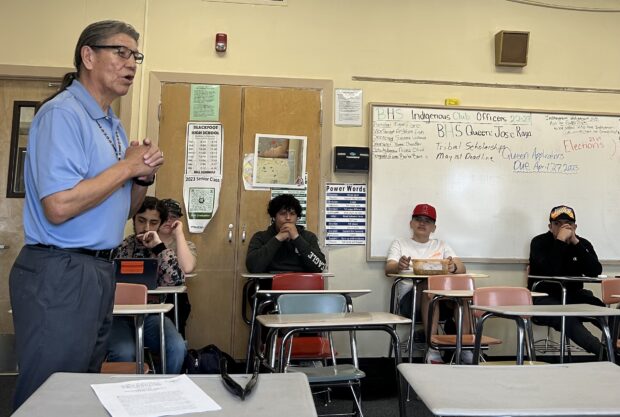

Merle Smith, a Native American teacher at Blackfoot High, widens his eyes when he talks about the boarding schools and how they would cut young boys’ hair.

Smith, who sports a long ponytail, said Native American people get their power from their hair and in his family, only other family members are allowed to touch it or style it.

While Miller and Smith are both well aware of the complicated relationship between Native Americans and formal education, both are doing their part to heal that rift.

Miller contributed to the Kessler Keener Foundation’s Native Voices project, which helps K-12 teachers integrate Native-centered content into their curriculum.

And Smith teaches a Native American culture class, where students learn about treaties, government policies and their impacts on tribal communities, and traditional cultural beliefs.

Those two factors — more Native American teachers in classrooms, and more Native American perspectives in the curriculum — will likely make the biggest difference in mending the frayed relationship between Indigenous communities and educational institutions.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.