The state of education for Idaho’s Native American students is appalling, according to a slew of data collected over the years.

In every major batch of educational data — whether it’s measuring test scores or graduation rates — there are significant achievement gaps between the state’s tribal youth and the general population.

Native American students are experiencing “urgent, urgent, urgent disparities” in Idaho’s K-12 schools, Vanessa Anthony-Stevens, a professor at the University of Idaho, said at a February State Board of Education meeting.

“These are starkly demonstrated in all the assessment data that we have available right now in the state of Idaho.”

Clearly, something needs to be done.

But Shawna Campbell-Daniels, director of the U of I’s Indigenous Knowledge for Effective Educator Program, or IKEEP, cautioned that too much emphasis on data and scores can be a detriment to Native American students.

Data can feed stereotypes of minority students being “less than.” Teachers, for example, might go into a classroom and expect less of Native American students because of data they’ve seen, or might make unfair assumptions.

“It’s not that they’re not smart or they can’t learn,” Campbell-Daniels said. “It’s because the school system’s not set up to serve them.”

“It’s not that they’re not smart or they can’t learn. It’s because the school system’s not set up to serve them.” — Shawna Campbell-Daniels on academic disparities between Native American students and their peers

And that’s the question the data should provoke, she said: How can schools and educators better support Native American students?

But organized efforts to answer that question and address shortcomings have fallen short.

The state’s Indian Education Strategic Plan started with ambitious goals for 2016 through 2021, but those were significantly pared back for 2021 through 2026. And the goals it does have in place have been criticized as vague and ineffectual.

Here’s a look at what the data shows, the strategic goals, and why stakeholders say state education leaders are failing Native American students.

The data that identify ‘urgent disparities’

In education, there are certain major benchmarks that measure how Idaho students are doing each year: the ISAT (Idaho’s standardized test), IRI (a reading test for Idaho’s youngest students), SAT (college entrance exam), graduation rates and chronic absenteeism (a relatively new metric).

And every three years, the State Department of Education ranks Idaho’s schools in order to identify the lowest performers (as required by the federal government).

All of these measuring sticks show that Idaho’s Native American students are behind. Here’s the data:

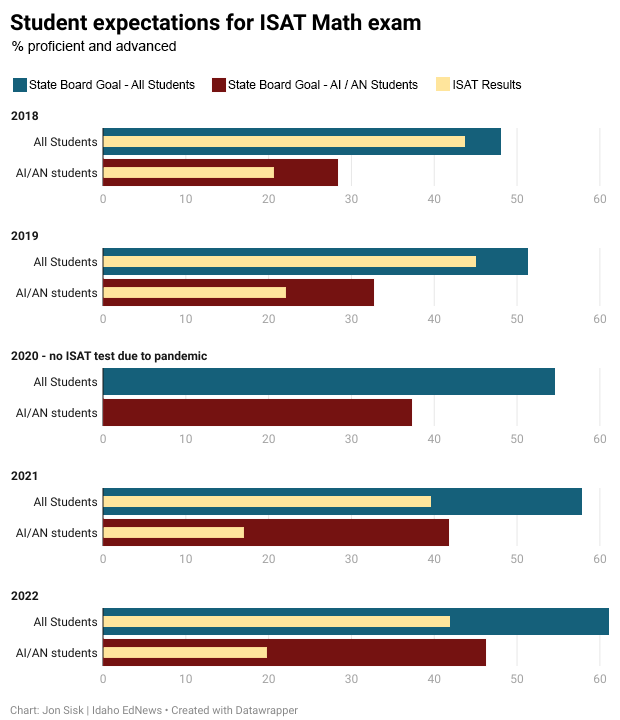

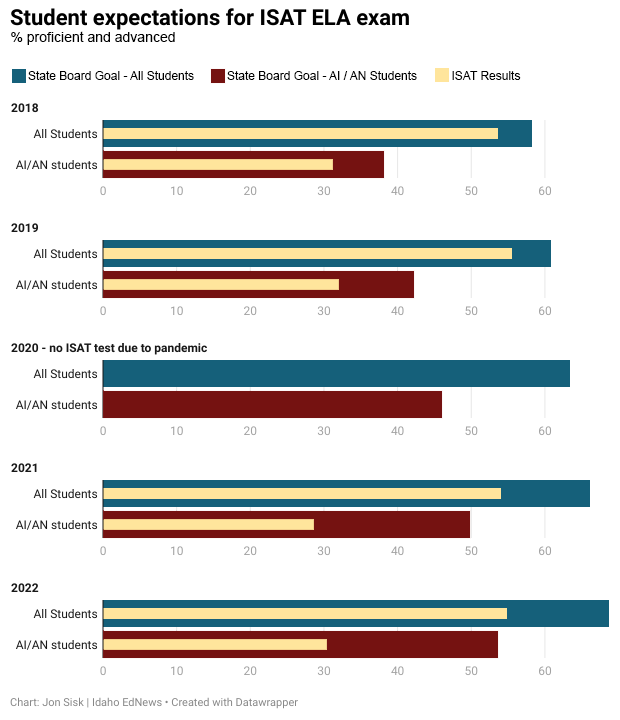

ISAT Scores

The Idaho Standards Achievement Test: The ISAT is administered each spring to all public school students in grades 3 through 8 and 10, gauging proficiency in English Language Arts (ELA) and math (in 2022, a newly-developed science portion of the test was administered to grades 5, 8, and 11). Scores are sorted into four categories: below basic, basic, proficient and advanced.

Idaho students in general still haven’t returned to pre-pandemic performances on the ISAT math or ELA exam — and neither have Native American students. But what has stayed consistent: Native American students tend to lag behind their peers by more than 22 percentage points.

It’s also worth noting that state education leaders set different goals for different groups of students, depending on demographics like race, wealth, ability level, and English language proficiency.

In its 2022 goals, the state set the second-lowest expectations for American Indian or Alaskan Native students. The lowest goal, of 43.5% proficient or advanced scores, was for students with disabilities.

Expectations for American Indian or Alaska Native students were also among the lowest for the 2022 ISAT ELA exam. Only students with disabilities and English learners had more limited goals.

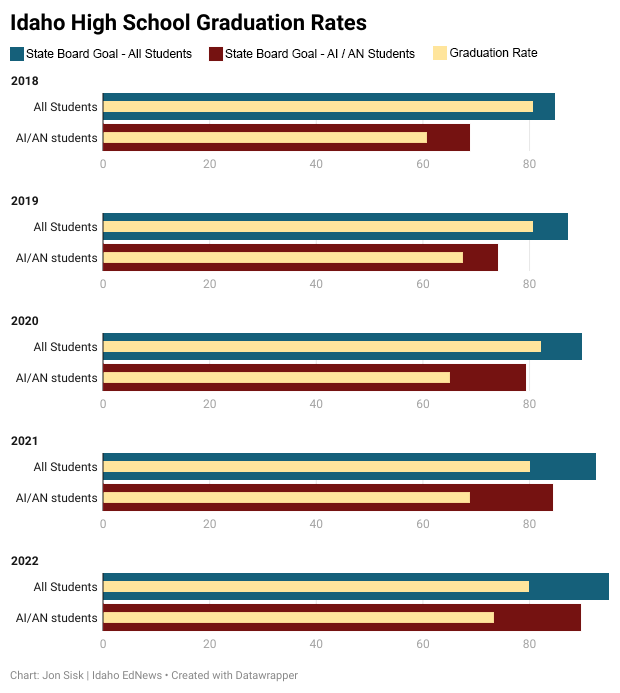

Graduation rates

Graduation rates: This is the percentage of students who graduate with high school diplomas in four years. That means students are tracked from ninth through 12th grades, so those who drop out before senior year are accounted for in final tallies.

Native American students are less likely to graduate in four years than their peers, though they did narrow the gap in 2022.

And state education leaders expect fewer American Indian and Alaska Native students to graduate on time than any other group.

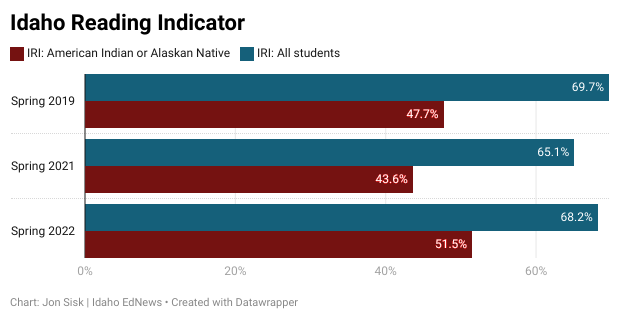

Idaho Reading Indicator

The Idaho Reading Indicator: All K-3 Idaho public school students take the IRI each fall and spring. Results are reported in three categories: at, near, or below grade level. The data shown here is for third graders.

Some progress has been seen on the IRI, as the achievement gap between Native American students and all students has grown smaller. Still, by spring 2022, just over half of Native American third graders were reading at grade level, as compared to 68% of all third graders.

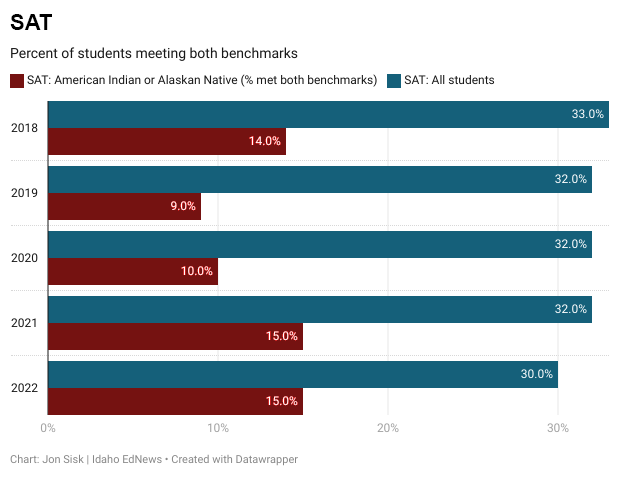

SAT

The SAT: The College Board created this national exam “to help students and educators assess student progress toward college readiness from year to year.” Most Idaho juniors take this test each spring and attempt to meet the benchmarks on two sections: math and evidence-based reading and writing. The test is required for entrance into some colleges, but is no longer a high school graduation requirement in Idaho.

On the SAT, there’s been minimal progress over the years for all students. While the achievement gap between the two groups has narrowed over the years, the percentage of Native American students meeting both benchmarks on the test is still half that of all students.

Chronic absenteeism

Chronic Absenteeism: The U.S. Department of Education defines chronic absenteeism as missing more than 15 days (or three weeks) in a school year, whether those absences are excused or unexcused.

Native American students are more likely to be regularly absent than their peers, and about a third of them are chronically absent. In 2021-22, they also had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism than any other subgroup.

State rankings of schools

State rankings: Every three years, the State Department of Education ranks Idaho’s schools in order to identify the lowest-performers (as required by the federal government). These rankings are based on a number of factors, such as standardized test scores, graduation rates, college and career readiness, student engagement, and English language learners’ growth. The goal is to identify these schools so the State Department can support and elevate them.

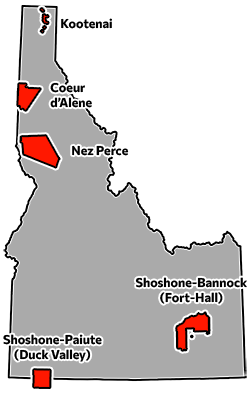

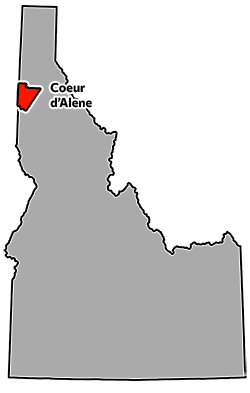

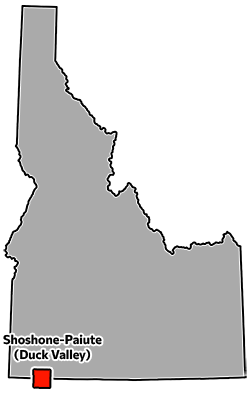

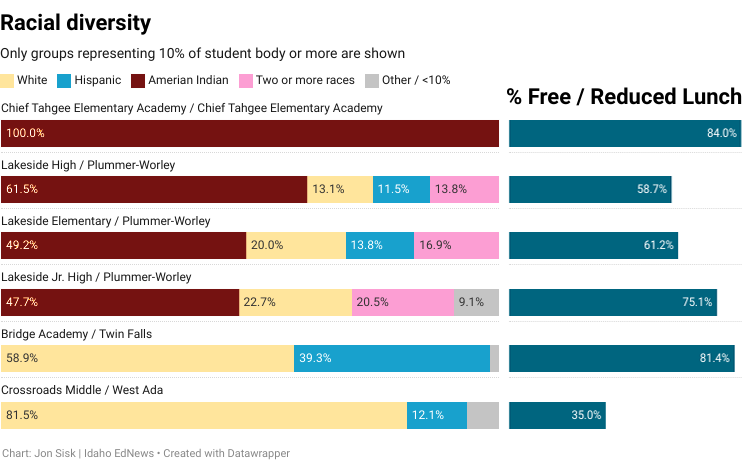

In the most recent rankings, from 2022, four of the six bottom-most ranked schools serve primarily Native American students and are located on or near reservations.

They include the Plummer-Worley School District’s three schools, which are located on the Coeur d’Alene Reservation, and Chief Tahgee Elementary Academy, which is located on the Fort Hall Reservation.

The school rankings exist so the State Department of Education can identify the lowest-performing schools and help elevate them. But Plummer-Worley’s three schools were ranked in the bottom seven the last time schools were ranked (2018) , and four years later, had sunk to the bottom six.

But now, the SDE has new leadership: Superintendent Debbie Critchfield.

Scott Graf, a spokesperson for the SDE, said efforts are underway to help struggling schools, like those in the Plummer-Worley School District:

- The SDE has an existing program that aims to boost underperforming schools.

- The SDE will be working with districts to improve their teacher collaboration practices and curricula.

In another three years, maybe it will be enough to elevate those schools — time will tell.

The problem with expecting less: data points to systemic issues

Considered altogether, the data indicates a staggering gap between Native American students and their peers. Year after year, they are behind in every major educational success indicator.

Recently, Leah Pandoah, a teacher at Shoshone-Bannock Jr./Sr. High, was encouraging her students to reset that narrative by challenging themselves and trying their best on standardized tests.

Historically, Native American students were put in the back row and given a piece of paper to doodle on while the rest of the class learned.

“The idea was to keep them occupied, they’re too stupid to get it,” she told her class. “That’s what they thought.”

Pandoah, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member, gets upset talking about it even today: “My history is based on people thinking that us Indians can’t think.”

By not trying on state tests, Pandoah said students are letting that narrative rule and are “agreeing to something that isn’t true.”

“Work harder than that,” she told her students. “Don’t settle for less.”

Idaho classrooms have been places where Native American students were forced to abandon their language and culture, where they were treated as inferior, and where — even today — state education leaders expect less from them.

As Campbell-Daniels said, the data points to a deficiency within the system.

But the State Board has also worked with stakeholders to set bold goals for the future of Native American students in Idaho — though enacting change and ensuring progress toward them is another story.

The State’s goals aim to help Idaho’s Native American students thrive …

In 2015, state education leaders created the first Indian Education Strategic Plan, a roadmap for ensuring that all “American Indian students in Idaho thrive, reach their full potential, and have access to educational services and opportunities.”

Though the plan wasn’t instated until 2015, efforts like these “are not new,” according to Johanna Jones, coordinator of State Department of Education’s Indian Education department.

“We, my relatives whom I work in solidarity with, are standing on the shoulders of indefatigable ancestors who broke trail for us. Their stories, their sacrifices, their success, — their pure survival are the reasons we are here,” Jones wrote in an email. “We are continuing their work and those who come after us will continue our work. A thorough education for ALL students depends on it.”

The SDE’S Office of Indian Education is a department of one — Jones. Her resources are limited, but she has advocated for Native American students by collaborating with other stakeholders throughout the state.

One such effort has been the Indian Education Committee — which includes members from the five Idaho tribes, the state’s two tribal schools, the State Board, and the state’s major universities and colleges. The committee, under the purview of the State Board of Education, created that first set of goals. Meant to be achieved between 2016 and 2021, the goals were lofty and bold, and raised the bar for educators, school systems, and American Indian students.

But by 2021, most of the goals had not been met. In the next iteration of the plan, which extends from 2021-2026, many of those aspirations were sidelined.

According to Jones and Patty Sanchez, the academic affairs program manager for the State Board of Education, the plan was trimmed to “focus on identifying and remedying systemic and institutional obstacles that create educational barriers for this demographic group.”

Essentially, the committee wanted to prioritize the most pressing needs.

Progress toward the new, pared-down goals since 2021 is unclear. Data on progress is collected annually and reported to the State Board in October, and the Indian Education Committee reviews that same data each December. However, progress was not reported in 2022 because the plan had just been updated in 2021.

The newest goals for 2021-2026 were not posted on the State Board’s website until May 10, nearly two years after they were first established. And they were not posted until EdNews twice pointed out (to two different agencies) that they were missing.

While a number of goals were set aside after 2016, Jones and Sanchez iterated that the plan’s two overarching goals remain in place: academic excellence and culturally relevant pedagogy. The more detailed goals are listed below:

The 2021-2026 goals for academic excellence include:

- More resources for public K-12 schools: Providing 5% more resources to districts and charters to “address culturally responsive school environments inclusive of family engagement, and social-emotional wellness that strengthens identity.”

- More high school graduates: Increase the percentage of American Indian high school graduates each year.

- More college graduates: Increase the percentage of American Indians graduating from an Idaho college each year in either six years (at a four-year institution) or three years (at a two-year institution)

- Improved college retention: Increase the percentage of freshman to sophomore retention of American Indians at Idaho colleges each year.

The 2021-2026 goals for culturally relevant pedagogy include:

- More training on culturally responsive teaching: Increase the number of college courses and education professional development credits in culturally responsive pedagogy and teaching.

- This goal is listed as “under development” and data on progress is “not currently collected at the state level.”

- Inform educators about tribes: Include tribal federal policies and Idaho tribal government in teacher, counselor, and administrator certification programs. The goal is to offer a minimum of three credit hours.

- More American Indian teachers: Increase the number of students accepted into and attending educator preparation programs at Idaho colleges. Every year, increase the number of students graduating from those programs or from a student personnel program.

- College/tribal MOAs: Develop Memoranda of Agreements between all public colleges and universities and Idaho tribes.

- Public school/tribal MOAs: Develop Memoranda of Agreements between all public secondary schools and individual tribes of Idaho.

And here are the goals that were dropped after 2016-2021:

- Opportunity Scholarship applicants: Increase the number of American Indian students who apply for the Opportunity Scholarship by 5 percent each year.

- Opportunity Scholarship recipients: Increase the number of American Indian students who receive the Opportunity Scholarship by 20 each year.

- FAFSA priority completions: Increase the number of American Indian students who complete the FAFSA by the priority deadline to 100%.

- AP/Dual enrollment/technical competency participation: Increase the number of American Indian students who participated in Advanced Opportunities: dual credit by 125 students; technical competency credit by 10%; AP exam by 10%.

- College enrollment: Increase the number of American Indian students enrolled in colleges after graduation by 400.

- IRI scores: Increase the percentage of students scoring proficient or higher on the IRI by 10%.

- SAT scores: Increase the % of American Indian students scoring proficient or higher on the SAT by 10%.

- College articulation: Increase the number of American Indian students that articulate to colleges by 60%.

- Completion: Decrease time to degree completion among American Indian students to 5 years.

- More college degrees: Increase the number of American Indian students earning a college degree: Associate’s degrees by 48 students; Bachelor’s degrees by 75; Master’s degrees by 16; Doctorate’s degrees by 5.

- More highly qualified teachers: Increase the number of highly qualified teachers in targeted schools to 100%.

- More American Indian administrators and counselors: Increase the number of certified American Indian administrators and counselors each year.

… But achieving those goals has been an uphill battle

Yvette Towersap, a policy analyst for the Shoshone Bannock Tribes, is unimpressed with the Indian Education Strategic Plan.

“It’s pretty skimpy,” she said, and added that the goals listed are vague.

Surrounding states have done better at incorporating Native American curriculum and recruiting Native American teachers.

In comparison, “Idaho has fourth grade,” Towersap said.

She’s referring to the Idaho history taught that year that includes historical information on tribes. For some Idaho students, that’s where their education on Native Americans starts and stops.

Anthony-Stevens is similarly blunt about the Indian Education goals.

As the principal investigator for IKEEP, a program that aims to get more Native American teachers in classrooms, Anthony-Stevens is well-known and respected among tribal communities. And she says the goals are well-intentioned but ineffective.

The biggest hangups: a lack of direct funding, accountability, and public visibility.

Federal funding meant to support Native American students comes with strings attached and isn’t always used effectively

Federal funding for American Indian or Alaska Native students is contingent on requirements like having an Indian Education Committee and strategic goals, Anthony-Stevens said. Those measures, then, are essentially in place to adhere to federal laws.

The funding she mentioned was promised to tribes in most treaty agreements (which often included provisions for education) and includes, at the K-12 level, Johnson-O’Malley and Title VI monies. Districts and charters can collect those funds to support Indigenous students.

Federal Title VI funding, for example, aims to support local schools and other entities:

- To meet the unique educational and culturally related academic needs of students, so that such students can meet the challenging state academic standards;

- to ensure that Indian students gain knowledge and understanding of Native communities, languages, tribal histories, traditions, and cultures; and

- to ensure that teachers, principals, other school leaders, and other staff who serve Indian students have the ability to provide culturally appropriate and effective instruction and supports to such students.

However, education leaders sometimes opt out of collecting those federal dollars in order to sidestep the requirements they come with — even though those funds would help Native American students. In other cases, schools collect the money but may or may not use it effectively, and oversight can be lacking.

Districts also have differing approaches to collecting and using the funds. In the Pocatello/Chubbuck School District, for example, the Shoshone-Bannock Tribal Youth Education Program administers and oversees how those funds are used. Blackfoot School District, however, oversees those funds itself. In the Lapwai School District, its Indian Education Department (a department that many districts do not have) takes charge.

State goals for Indian Education lack funding and enforcement

But the state’s strategic goals do not have their own specific, appropriated funding earmarked to make them happen. It’s basically up to stakeholders, like superintendents and other leaders, to decide if they want to work toward them with their own time and resources, Anthony-Stevens said.

“There’s a minimal investment at best in Indian education in our state.”

Plus, there’s very little — if any — accountability measures driving stakeholders to meet the stated targets.

“It makes progress toward those goals extremely slow if not non-existent,” Anthony-Stevens said.

And she said the goals are not broadcast well to the general public, and many are unaware that they exist.

But she is grateful for the existence of a relationship between the State Board and Indian Education Committee, and for the annual Idaho Indian Education Summit.

While the State Board is Idaho’s policy-making agency when it comes to education, the SDE is responsible for putting those plans into action. Within Critchfield’s first few months in office, she has “met with tribes throughout the state to listen to their perspectives on the state of Indian Education in Idaho,” Graf wrote in an email. Those meetings are ongoing and “an important first step to gain additional perspective, assess what issues exist and how they can be addressed.”

The SDE and State Board also plan to review Indian Education resources “to ensure they’re being used in a way that provides maximum benefit,” Graf wrote.

For now, without teeth or funds to back the strategic plan, the burden to improve education for Native American students has largely fallen on those who care the most. They are individuals like the team at IKEEP; Native American teachers, paraprofessionals, and education leaders; tribal elders and officials; and Native American students themselves.

They’re pushing for visibility in Idaho classrooms — places where teachers once strove to erase Indigenous identities — through more Native American teachers, more Native American voices and perspectives in the curriculum, and more acknowledgement and celebrations of Native American culture.

As stakeholders will say to anyone who will listen: Native Americans are more than photos in history books. They are neighbors and classmates, entire communities that are thriving today and everyday, and like all Idaho students, they deserve an education that launches them into the most successful future possible.

*Editor’s note: In this story, the term “American Indians” was sometimes used to refer to Native American students in order to match the State Board and/or State Department of Education’s terminology.

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.

This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.