The pandemic has slowed Idaho’s uninterrupted dual-credit surge.

High school students are having a hard time squeezing taxpayer-funded college courses into class schedules turned upside down by the coronavirus. Consequently, dual-credit enrollment has suffered.

Nonetheless, Gov. Brad Little wants to put an additional $9.5 million into the budget line item that covers dual-credit programs. He expects enrollment to rebound after the pandemic. And in the big picture, Little is trying to push an education budget that will allow Idaho schools to get back as close to normal, as quickly as possible.

“We’re pretty adamant in getting on track next year,” Greg Wilson, Little’s education adviser, said Wednesday.

Before falling off track, Idaho’s advanced opportunities program was a runaway hit with students, and a centerpiece in the state’s multimillion-dollar push to convince more high school students to continue their education. While that continues to be an uphill struggle — as evidenced by the latest “go-on rates” released this month — there’s no disputing the popularity of dual credit, which accounts for the bulk of advanced opportunities dollars.

Before falling off track, Idaho’s advanced opportunities program was a runaway hit with students, and a centerpiece in the state’s multimillion-dollar push to convince more high school students to continue their education. While that continues to be an uphill struggle — as evidenced by the latest “go-on rates” released this month — there’s no disputing the popularity of dual credit, which accounts for the bulk of advanced opportunities dollars.

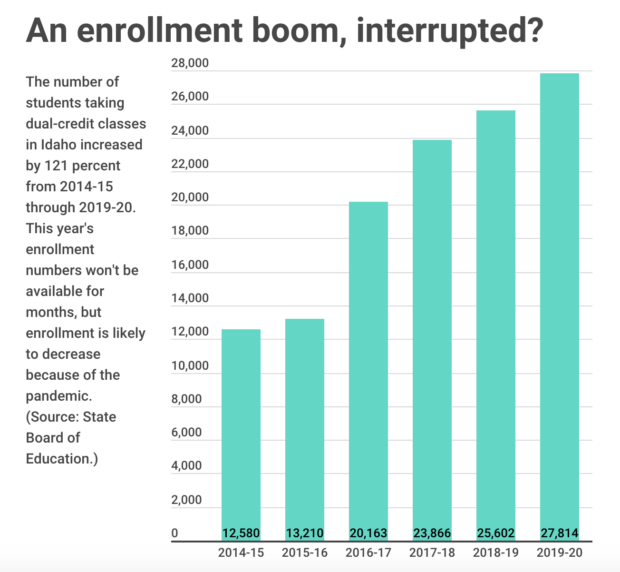

From 2014-15 to 2017-18, the number of students enrolled in dual-credit courses nearly doubled. The growth continued after that, although at a slower rate. In 2019-20, at the onset of the pandemic, dual-credit enrollment reached 27,814.

It will be months before the State Department of Education has firm numbers for 2020-21, because the department compiles those figures as it reimburses students for the courses they take. But based on the SDE’s preliminary numbers, dual-credit enrollment dropped by 18 percent from fall 2019 to fall 2020.

The causes vary, but most likely, they all loop back to the pandemic and the shift to online or hybrid learning: scheduling problems; limited access to school advisers; a general level of stress and uncertainty. Eric Studebaker, the SDE’s director of student engagement and safety coordination, urged his own daughters to put dual credit on hold this year, because he wasn’t sure what the school year would look like.

“I was more concerned with their success and happiness,” he said. “I didn’t want to overload them.”

But even if dual-credit enrollment falls this year, the advanced opportunities program is still under water from a fiscal perspective. That’s part of the reasoning behind Little’s request for an added $9.5 million.

Last year’s advanced opportunities budget was $20 million; costs came in at $23 million, with $19 million going for dual-credit courses, said Brock Astle, SDE’s advanced opportunities coordinator. The state has had to dip into its public schools rainy-day account to cover the difference, and Little wants to keep these kind of budget withdrawals to a minimum, Wilson said.

The rest of the $9.5 million would go toward future growth — and meeting future demand. And the conventional wisdom is that, as soon as the pandemic wanes, students will flock back to the dual credit program.

“I think it will continue to grow, although the growth is slowing down,” said Senate Education Committee Chairman Steven Thayn, R-Emmett, a longtime advocate for dual credit.

And Studebaker wouldn’t be surprised to see enrollment rebound quickly. K-12 students have a $4,125 advanced opportunities line of credit they can use for dual-credit courses (or Advanced Placement or International Baccalaureate programs or summer overload classes). When schools return to more of a normal schedule, there could be a pent-up student demand for dual-credit programs.

Or, perhaps, it’s already playing out that way.

In October, Boise State University turned in its fall enrollment numbers, and reported a stunning 37 percent decrease in dual-credit students. The year-to-year decrease now stands at 20 percent, Mark Wheeler, dean of Boise State’s Division of Extended Studies, said in a Thursday interview.

He attributes much of the dropoff, and the recent narrowing of the enrollment gap, to scheduling issues. As the West Ada School District shifted abruptly from a semester calendar to a quarterly calendar, students in the state’s largest district struggled to squeeze in dual credit. Now, those students are starting to come back.

“I think the beginning of the school year was a scramble for students and administrators alike,” he said.

Gauging the success of the dual-credit program is a tricky proposition. Proponents such as Wheeler say students who take dual-credit courses in high school are better prepared for college. The offer of college credits, at no cost, certainly helps make college more affordable. The question is whether this program is helping Idaho get more students into the higher education system — the state’s long-range goal — or if the program is simply helping students who were college-bound in the first place.

But Little is betting that the dual-credit enrollment drop is a one-year blip — and that appears to be a safe bet. Considering that lawmakers have eagerly put money into an ever-increasing advanced opportunities program budget, Little’s proposal to increase the budget from $20 million to $29.5 million is probably a safe wager as well.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.