It’s not news that Idaho is growing — especially to residents of the fast-growing Treasure Valley — but it’s important to look at how the state is growing.

Senior citizens represent the fastest growing segment of the state’s population, according to Census Bureau numbers the Idaho Department of Labor released this week.

This means Idaho school districts might be pitching bond issues and levy proposals to an aging electorate — and a growing share of voters with no children in the schools.

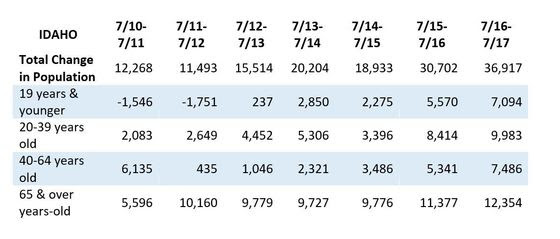

First, the numbers. This Department of Labor table shows year-to-year population growth, with breakdowns by age group.

Idaho added nearly 37,000 new residents from mid-2016 through mid-2017. But seniors accounted for fully one-third of that growth.

Yes, Idaho is growing across the board. The state’s birth rate slowed during the Great Recession — as evidenced by those population decreases in the 19-and-under demographic. But the state added 7,000 young residents from 2016 through 2017.

If that trend continues, it will drive up school enrollment — and put more pressure on districts to pass bond issues for new schools, or supplemental levies to fill in other spending needs.

At the risk of belaboring an obvious point, most of those people in the 19-and-under demographic cannot vote in school elections. Senior citizens can.

That’s no small matter for school officials, of course.

Since statehood, districts have been expected to cover their own building costs — and that invariably requires districts to seek bond issues, which need a two-thirds supermajority to pass. That’s a challenging hurdle, and districts don’t always get there the first time out. Just ask the Idaho Falls School District, which will go to voters in August with a $99.5 million proposal to upgrade its high schools, nine months after a $110 million proposal failed.

Meanwhile, districts have grown increasingly reliant on supplemental levies, especially over the past decade. In 2017-18, 93 of Idaho’s 115 school districts collected a record $194.7 million in supplemental levies. These levies are easier to pass, requiring only a simple majority. But the levies only run a maximum of two years. So while many district leaders say the levy dollars are needed to cover day-to-day demands, from salaries and benefits to transportation, they also have to go back to the electorate every year or two to keep the levies on the books.

And as the Census numbers indicate, that electorate is ever changing.