When Shawna Campbell-Daniels was in college at Washington State University, she was shocked by her peers’ ignorance when it came to Native American people like herself.

They would ask questions like: “Do you still live in teepees?” or, “Is there running water on the reservation?”

Others would try to guess her ethnicity. Was she Hispanic? Asian? Hawaiian? They rarely guessed Native American.

It made her feel invisible, and over time, she realized that education is “not designed to serve Native communities.”

Campbell-Daniels, a Coeur d’Alene tribal member, grew up on the Coeur d’Alene reservation. She attended public schools there, where she said her education did not prepare her for college.

When she returned to her hometown as an adult, she saw the public schools failing her son, too. As part of the fourth-grade Idaho history curriculum — which, for some Idaho students, is the bulk of the education they receive on Native Americans — her son’s teacher provided handouts on faraway tribes that contained erroneous, negative information.

It was a lost opportunity, Campbell-Daniels thought. Why not learn about the local tribes and connect to students’ identities and backgrounds? But it was worse than that — it was harmful.

“I thought about my son being in that class and hearing that type of narrative about who he is and how that would make him feel as the only (Native American) in the classroom, and it really just broke my heart,” she said. “And that is something that I think fundamentally needs changed in education.”

An essential part of that is getting more Native American teachers in the classroom, which is exactly what Campbell-Daniels is working on.

Campbell-Daniels is a postdoctoral fellow and project director for the University of Idaho’s Indigenous Knowledge for Effective Educator Program, or IKEEP. The program “prepares and certifies culturally responsive Indigenous teachers to meet the unique needs of Native American students in K-12 schools.”

Now in its seventh year, the program has sparked a 400 to 500% increase in American Indian and Alaskan Native enrollment in the university’s teacher preparation programs, according to Vanessa Anthony-Stevens, a professor at U of I and IKEEP’s principal investigator.

Our story “is about changing the conditions of education so that Native children, too, can thrive in the institutions that we call schools and beyond.” — Vanessa Anthony-Stevens, principal investigator, IKEEP

The IKEEP program was built to address “the near invisibility of Indigenous teachers in the workforce,” Anthony-Stevens told trustees at a February State Board of Education meeting.

Most Native American students in Idaho attend public schools, and even in schools with high Indigenous populations, “we see very, very few Native teachers in front of classrooms.”

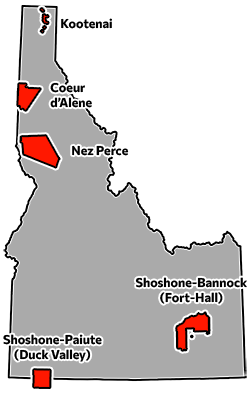

In Idaho, only 56 of the state’s 17,594 teachers (or 0.3%) are Native American. Comparatively, there are 3,146 Native American students out of 312,000 statewide (or 1%).

The program also aims to address “the urgent, urgent, urgent disparities that are experienced by our Native youth in K-12 schools. These are starkly demonstrated in all the assessment data that we have available right now in the state of Idaho.”

But from those dire starting points, Anthony-Stevens sees a brighter future.

“Our story begins with these recognitions, but is a story about changing the conditions of education so that Native children, too, can thrive in the institutions that we call schools and beyond.”

IKEEP shepherds a new generation of teachers into schools, defying stereotypes of who is and can be a teacher

The IKEEP program recruits Native Americans from across the country to enter its program and become teachers. Some stay in Idaho, others come from out of state and return to their communities.

Since its inception in 2016, IKEEP has graduated three cohorts of new teachers. The third was the largest, with 11 students representing nine tribes from six different states.

IKEEP supports its teachers through their first two years in the classroom with mentoring, feedback sessions, meetings and seminars, and more. Campbell-Daniels says those continuing services are essential.

“It can be really hard, especially in those first years,” she said. “There’s a whole slew of things that Native teachers have to maneuver once they are practicing teachers in a school district. There’s often not a system of support set up for them, and it can be very lonely … And they might be the only Native teacher.”

Chrystyna Hernandez is one of the IKEEP graduates, and she now teaches at Owyhee Combined School on the Duck Valley Reservation, where nearly 100% of the students are Native American. Hernandez is a member of the Shoshone-Paiute tribes.

At a February State Board meeting, she said the program was a “truly, truly meaningful education that honors me as a student and modeled how to honor my students in my community.”

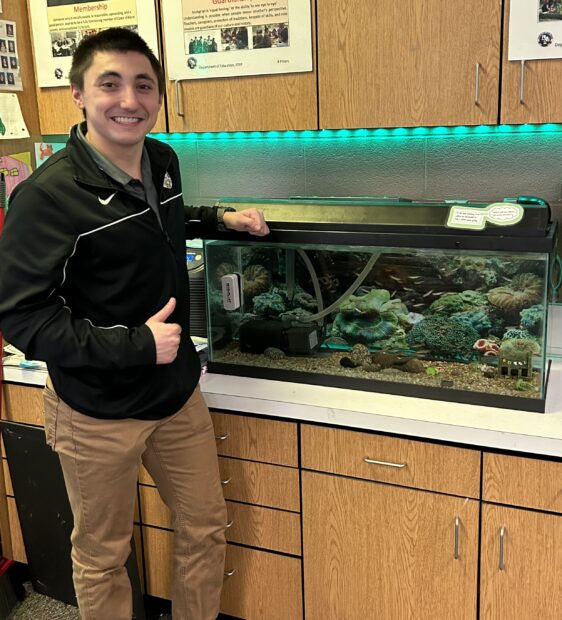

Nicholas Eldredge, a fourth-grade teacher at the Coeur d’Alene Tribal School, is another IKEEP alumnus and a descendant of the Salish-Kootenai tribes.

He ties culture into his classroom when possible, like raising native fish to eventually be released in a nearby creek.

Eldredge grew up in Post Falls and “very outside of Native cultures.” The program helped connect him to his identity, and now he’s giving students something he never had: a Native American teacher.

But even at his tribally run school with a 100% Native American population, there are only two Indigenous teachers.

Anthony-Stevens said that lack of Native American teachers, especially on reservations, is “one of the most glaring, telling impacts of colonization.”

“The lack of representation in the classroom is not an accidental occurrence,” she said.

It was borne of “some very intentional choices” when the federal government selected who would oversee boarding schools, which Anthony-Stevens compared to an “incarceration of Indigenous youth.” And oftentimes, those teachers were white, Christian women.

Systems like that established “what type of person gets to be a teacher and what type of knowledge you need to be a teacher.” And even today, the image of a typical teacher has not changed much. That makes it harder for Native Americans to aspire to enter education.

“When you don’t see any teachers who look like you or who are from your community, or maybe you’ve had hostile experiences with teachers, it’s very hard to envision yourself wanting to be in that role,” Anthony-Stevens said.

But getting more Native American teachers in the classroom stands to benefit more than just minority populations.

All kids need Native American teachers, all teachers need cultural competence

Native teachers can provide all students with a more complete history of their country, Anthony-Stevens said. The realities they can share are “quite different than the kinds of textbook realities that we’ve been peddling for a while.”

And diverse teachers are good for the country as a whole.

“Indigenous teacher education … is an investment in tribal nation building,” Anthony-Stevens told State Board members in February. “Strong nations support the health and wellbeing of strong citizens, who in turn contribute to the diverse needs of our democracy.”

And IKEEP does more than prepare Native American teachers. It also offers an online professional development course on Idaho’s five tribes for current teachers, and the course will soon be available to teachers-to-be. The course was created in conjunction with the State Department of Education.

Anthony-Stevens said she would love to see school districts have small groups of teachers sign up to take the class together and organize a study group around it. “We haven’t had anyone take us up on that yet, but we hope that they will.”

All teachers — not just Native American teachers — need to come to the classroom equipped with knowledge about Idaho’s five tribes.

“Teachers need to come into the classroom conscious that there are multiple perspectives on who we are as Idahoans … and be inclusive of the full history of Idaho and the ways in which we receive that information differently,” Anthony-Stevens said.

An impressive program — that’s underfunded

The IKEEP program is making crucial headway on two goals established by the state: to increase the number of Native American teachers and to increase Native American knowledge among educators and educators in training.

In a February board meeting, IKEEP staff presented information on the program to trustees — including State Superintendent Debbie Critchfield, who seemed impressed.

Critchfield said she had recently visited with Chief Allan, chairman of the Coeur d’Alene tribe. The No. 1 concern he had was finding and retaining teachers. While that’s been a statewide concern, Critchfield said the conversation helped her better understand the unique needs of tribes.

“They want teachers that look like the members of their community, and that is very important,” she said.

State Board President Linda Clark expressed interest in expanding the IKEEP program to all Idaho universities and colleges. A program designed to increase Hispanic educators is needed as well, she said.

“What resources would it take for us to begin to replicate this program in other parts of the state?” she asked.

And that question struck at the heart of the matter.

“Plans to expand are always things that we people are envisioning,” Anthony-Stevens told EdNews. “But how we expand and with what support we expand is something that’s really important to have as part of the dialogue.”

She said she’s been at meetings like February’s her whole career. People are impressed and inspired by the work IKEEP is doing.

“And you know what they do after? Nothing,” she said. “Is the state giving any dollars to IKEEP? Zero.”

The IKEEP program is primarily funded by grants, though Anthony-Stevens acknowledged that her salary is paid by taxpayers.

“It is mind-blowing to me, the ways in which our state and other states absolutely fail to invest in Indian education,” she said. “(Because) we know that if there’s resources, things will change.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report. This story is part of a series that was made possible with a generous grant from the Education Writers Association.