Kurt Liebich had been tracking the delta variant — and its midsummer spread across states such as Florida and Mississippi.

The problem hit home in early August, when the State Board of Education president got a briefing from Kathryn Turner, Idaho’s deputy epidemiologist. Turner walked through the modeling, which predicted a sharp increase in new coronavirus cases, based on Idaho’s languid vaccination rates.

“We’re actually tracking pretty darned close to what those models predicted,” Liebich said Wednesday.

Idaho’s K-12 coronavirus explosion is sudden. But it’s not a surprise. Everything that is now unfolding was foreseeable.

- The latest surge in cases, as the coronavirus morphs into a pandemic of the unvaccinated.

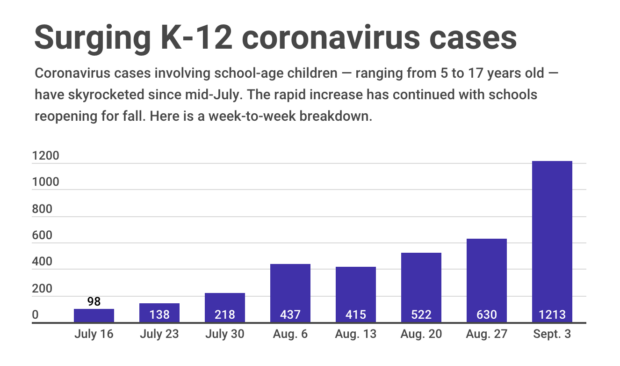

A sharp uptick of cases involving children — kids under 12, who can’t get vaccinated; and 12- to 17-year-olds, who are largely going unvaccinated.

A sharp uptick of cases involving children — kids under 12, who can’t get vaccinated; and 12- to 17-year-olds, who are largely going unvaccinated.- A record-breaking hospitalization rate, forcing North Idaho hospitals to adopt crisis standards of care, a chilling system of medical rationing.

No surprises.

But it’s fair to ask if state officials and educators were slow to see the looming threat. When the delta variant alarms began sounding from other states, Idaho leaders took a wait-and-see approach, as Idaho Education News reported on July 8. “I think it’s kind of early,” Greg Wilson, Gov. Brad Little’s education adviser, said at the time. “l think a lot of us are kind of watching how this plays out.”

Like Liebich, Wilson said the picture changed as the modeling came into focus. “The full impact of delta became clear about three weeks ago,” Wilson said Thursday.

Could the state have said more, or done more, earlier in the summer?

In a prepared statement Thursday, state superintendent Sherri Ybarra’s office didn’t address the state’s initial response: “Our schools are doing all they can to deal with the surge in COVID cases, which is happening across the nation.”

“Hindsight’s always 20-20,” said Liebich, saying the diversity of Idaho’s schools and communities doesn’t lend itself to a sweeping statewide edict. He emphasized the state’s approach: Provide local administrators and trustees with the data, and let them make their own decisions. As an example, the State Board held an Aug. 19 briefing for local educators, allowing them to hear Turner’s delta variant modeling presentation firsthand.

In their quest to embrace local control, and in Little’s quest to avoid anything resembling a COVID mandate, the state hasn’t always delivered a clear message about what schools should do about the delta variant.

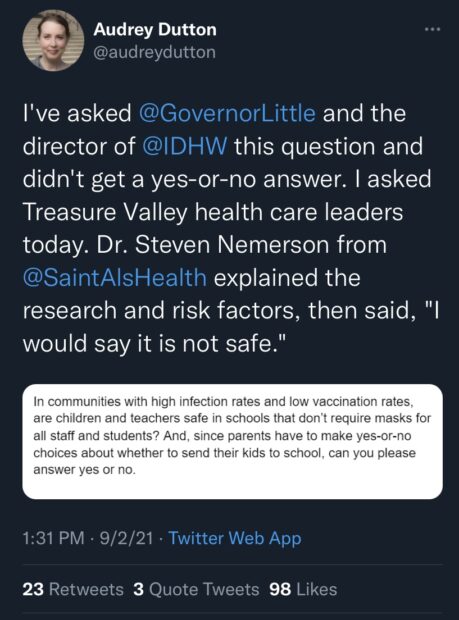

Idaho Capital Sun reporter Audrey Dutton tried to pin down state leaders, to little avail. During an Aug. 31 media briefing, Department of Health and Welfare Director Dave Jeppesen spoke in favor of Centers for Disease Control guidelines, which call for mask usage in schools in communities with high coronavirus spread. But when Dutton asked for a yes-or-no answer, Jeppesen stopped short of saying that unmasked kids are unsafe. (Dr. Steven Nemerson, chief clinical officer for the Saint Alphonsus Health System, did say he thinks unmasked kids and teachers in communities with high infection rates and low vaccination rates are at risk. Dutton sent Idaho Education News a transcript of her Sept. 2 interview with Nemerson.)

Idaho Capital Sun reporter Audrey Dutton tried to pin down state leaders, to little avail. During an Aug. 31 media briefing, Department of Health and Welfare Director Dave Jeppesen spoke in favor of Centers for Disease Control guidelines, which call for mask usage in schools in communities with high coronavirus spread. But when Dutton asked for a yes-or-no answer, Jeppesen stopped short of saying that unmasked kids are unsafe. (Dr. Steven Nemerson, chief clinical officer for the Saint Alphonsus Health System, did say he thinks unmasked kids and teachers in communities with high infection rates and low vaccination rates are at risk. Dutton sent Idaho Education News a transcript of her Sept. 2 interview with Nemerson.)

Is it really so hard for state leaders to say the same thing? Especially after they were slow to sound the alarm about the delta variant? And especially when the delta variant spike will probably get worse before it gets better?

State epidemiologist Christine Hahn, who has proven to be a straight shooter through the pandemic, was candid during this week’s Health and Welfare media briefing. She favors masking — not just as a health official, but as the mother of kids in the Boise School District, where masks are required. And she voiced her concerns about the patchwork of school pandemic protocols, an outgrowth of the local control approach.

“I think there’s a lot that schools can and should be doing. I know many of them are. But I don’t think all of them are, consistently, across the board,” she said. “I think if we could increase the use of social distancing, masking and vaccination among those who are eligible, we would be doing a lot better at keeping our kids in school.”

On Wednesday, Liebich had a similar message. “We’re learning every week in terms of what’s working and what isn’t,” he said, citing Boise’s masking requirement as an example of an effective policy.

Messaging matters. Timing also matters.

This is a critical moment in Idaho’s battle with the delta variant. Overall, last week’s new cases came in just shy of 8,000 — but modeling suggests that, come mid-October, this number could crest at a staggering 30,000 cases. Unvaccinated kids are accounting for an increasing share of these cases, prompting concerns that the virus will spread from schools into households and communities.

What state leaders say, and say now, might be even more important than the warnings that went unsaid in July. Consider Tuesday’s events. As North Idaho’s swamped hospitals began rationing health care, something never before seen in the state, the Coeur d’Alene School District opened fall classes. The district recommends masks, but doesn’t require them.

And timing matters even more when the clock is ticking.

Little’s office wants to help schools identify best practices that will help them keep the doors open, Wilson said. Wilson would like a few more weeks of data — but he’s fully aware the worst of the delta wave could hit in a few more weeks.

“We’re trying to project, and respond,” Wilson said. “It’s difficult. There’s no question about it.”

As Liebich tracks the coronavirus numbers daily, as well as school attendance rates, he straddles the line between optimism and worry. Ultimately, he believes more kids will spend more of the 2021-22 academic year in the classroom, getting the face-to-face instruction they need. Mask requirements need not be permanent, he said, because the delta variant will eventually dissipate.

But the new school year, the third interrupted by COVID-19, will get off to a rocky start.

“The next four to six weeks are going to be really challenging,” Liebich said.

How challenging?

Ultimately, that depends on what local school leaders do next.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for his stories each Thursday.