A few weeks into a delta variant school year, the pandemic is changing.

More kids are getting the coronavirus.

Yes, some kids are getting very sick. Yes, schools are struggling with the effects.

And yes, it’s likely to get worse.

Here’s a look at five hard realities.

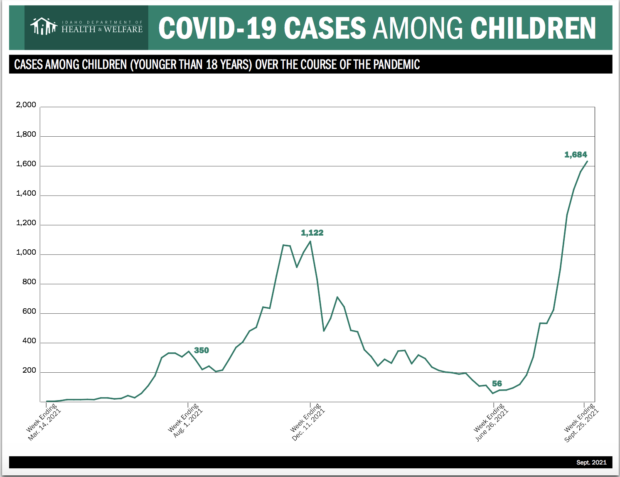

1. The numbers have already set disturbing records

Before the delta variant brought the coronavirus roaring back to life, the state logged just 56 child cases of the virus for the week ending June 26.

Three months later, that weekly total reached a record 1,684 cases — a thirtyfold increase. Cases involving kids far exceed numbers from last fall, the state’s previous coronavirus surge.

Three months later, that weekly total reached a record 1,684 cases — a thirtyfold increase. Cases involving kids far exceed numbers from last fall, the state’s previous coronavirus surge.

None of this happened overnight. The child case numbers began climbing even before fair season and the first day of school, as Idaho Education News reported in early September. But the surge has only continued since the start of fall classes.

None of this has happened in a vacuum, either. As the delta variant races through an unvaccinated population, it is finding a foothold in schools. According to Centers for Disease Control data, most of last week’s highest infection rates involved kids, from 5 to 17 years old. That’s true both nationally and in the Pacific Northwest.

It’s impossible to compare Idaho’s child case surge to all other states. That’s because jurisdictions break down demographics differently: 16 jurisdictions, like Idaho, report case numbers involving kids through age 17, while the remaining states use different categories.

Here’s an incomplete but apples-to-apples comparison from the American Academy of Pediatrics, which tracks childhood cases weekly. Among the 16 jurisdictions that report cases involving kids through age 17, Idaho’s infection rate ranks 11th — higher than New York City and New Jersey, slightly lower than California, significantly lower than Arkansas and Mississippi.

2. The surge is affecting kids’ health

It’s a recurring claim: Kids are at no risk from COVID-19.

Health professionals see a different reality.

COVID-19 left one Treasure Valley teenager with a pacemaker, possibly for life, said Dr. David Peterman, a pediatrician and CEO of Primary Health Medical Group.

Two other students — superb athletes before getting the virus are COVID long-haulers. One needed four to five months to recover, Peterman said.

While relatively rare, acute COVID cases can leave kids dependent on oxygen or a ventilator, said Dr. Kenny Bramwell, medical director for the St. Luke’s Health System children’s hospital.

Other children who contract COVID later wind up in the hospital with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, which can strike the heart, lungs, brain or other organs, Bramwell said. Idaho has reported 31 MIS-C cases.

To date, no Idaho child has died from COVID-19. In the St. Luke’s system, only five children are hospitalized with COVID-19, compared to 300 adults. And the children who are hospitalized — more than 200 in Idaho so far — tend to recover more quickly and more completely than adults. “By and large they don’t have the devastating consequences that many of our adults are having,” Bramwell said.

But Idaho’s overwhelmed hospital system is teetering on a knife’s edge. All hospitals have the state’s authorization to adopt crisis standards of care: a grim system of health rationing. In other states, the delta variant surge has strained hospital systems so much that they have had to cannibalize pediatric space to care for sick adults. Idaho isn’t there yet, but the state’s record COVID-19 hospitalizations have Bramwell worried.

“We are running out of real estate.”

3. The surge is affecting schools

Unlike last fall — when Idaho school districts operated under a patchwork of face-to-face, online and hybrid learning — most schools are fully open.

But that doesn’t mean things have been easy.

The Nampa School District has logged 600 student cases in six weeks — and those are just the cases parents report and school officials can confirm. Last school year, it took Nampa until mid-January to reach 600 student cases, Superintendent Paula Kellerer told reporters this week.

The case numbers are driving up student absentee rates, running from 10 to 15 percent in Nampa schools, and those attendance numbers could affect state funding.

Staffing is a pressing issue. Across Southwest Idaho, more than 200 classrooms need substitute teachers. “They’re open classrooms, and schools are scrambling to meet those needs,” Kellerer said.

And on Tuesday, the virus and the staff shortages hit Nampa directly.

With 14 teachers out — two testing positive for coronavirus, others waiting for test results, others home taking care of sick kids — Endeavor Elementary School closed its doors for the remainder of the week. Closing one school is a form of staffing triage.

“This closure will allow us to use our limited substitute resources at other buildings where we are seeing increased need,” Endeavor Principal Heather Yarbrough said in an email to parents.

4. Some school boards aren’t helping

On Tuesday, Kellerer wrapped up her rundown on COVID in the schools with an appeal to Idahoans: get vaccinated and wear masks. “Help us keep our kids in school by working the mitigation strategies out in the community.”

But Nampa’s own board of trustees punted on a mask mandate earlier this month, voting to keep masks optional. A spilt Pocatello-Chubbuck School Board adopted an optional policy Tuesday. And after some 200 angry patrons swarmed district headquarters Friday, forcing trustees to abruptly cancel a meeting, Coeur d’Alene School Board Chair Jennifer Brumley says trustees will not revisit the issue.

During their news conference Wednesday, Bramwell and Peterman didn’t even try to hide their frustration.

“I’m not coming up with any nice words to describe the way that the school boards have responded to this problem,” Bramwell said. “They just don’t seem to understand the importance of masks in public settings. Masks to me are a rather trivial thing to wear in the course of my day as an emergency doctor.”

Calling the decisions of some school boards “shameful,” Peterman also came prepared with research: positive coronavirus test rates, by zip code, for kids in the Treasure Valley.

All the test rates are high, well above the 5 percent threshold that suggests whether an outbreak is out of control. But in Boise, where masks are required in schools, last week’s rate was 17 percent. The rate in West Ada was 21 percent — and possibly stabilizing, two weeks into a school mask mandate, Peterman said. Nampa’s positive test rate was 30 percent, and showing no signs of slowing down.

5. Things are probably going to get worse

Nearly all of the state’s coronavirus metrics are going the wrong way.

Cases are climbing — so fast that the state says it is plowing through investigating a backlog of 11,500 positive test results. The crushing hospitalization rates show no sign of slowing. Grasping for any good news, Department of Health and Welfare Director Dave Jeppesen this week pointed to a slight decrease in the overall positive test rate — a leading indicator that might suggest the case surge is slowing down.

Maybe. Or maybe not.

The latest modeling suggests that Idaho’s case numbers could reach 21,000 a week by mid-November, almost double the peak from last fall. And that translates to 1,900 new hospitalizations in a one-week span (compared to current hospitalizations, running at about 800) and a record weekly death toll exceeding 300.

And those models are based on national data — and national case numbers that are showing signs of a decline, which isn’t happening in Idaho.

“In Idaho specifically, we’re tracking at the high end of the projections,” deputy state epidemiologist Kathryn Turner said during Health and Welfare’s weekly media briefing Tuesday.

Which points to a grim reality. More cases involving kids.

During Tuesday’s briefing, Division of Public Health Administrator Elke Shaw-Tulloch fought back tears as she talked about a pandemic that is striking a younger, unvaccinated population — and an anti-public health narrative that is leaving Idaho’s young people at risk. And she talked about reading each and every COVID death notice that has crossed her desk: now more than 2,850, and counting.

“I feel it’s important to honor them by reading their names and acknowledging their humanness,” she said, her voice wavering. “I worry every single day about the potential of seeing a child’s death notice.”

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for his stories each Thursday.