Many trustees demanded this.

They wanted to decide whether to open or close schools. They didn’t want to defer to the State Board of Education or health districts. Now they have the authority, and all the pressure and criticism that comes with it.

Is it one of those be-careful-what-you-wish-for things?

Troy Rohn chuckled, then said, “That’s probably a good point.”

Rohn was in that decisionmaking role until Sept. 24, when he resigned from the Boise school board. A month after stepping down — and stepping away from the agonizing school reopening debate — he commends his colleagues who are sticking it out. It’s an “impossible situation,” he said, and he’s not sure why anyone would want to stay on.

“I feel for these trustees, I really do,” he said Wednesday. “(And) it’s probably going to last through at least this year.”

That forecast is the last thing West Ada trustees needed to hear — six weeks into what figures to be a long school year.

It really is only six weeks ago that trustees were under fire for starting the school year online, with technical glitches that left parents frazzled and frustrated. Days later, 13 area legislators urged trustees to step up an incremental reopening plan, and bring 38,000 students back to school full-time. Striking a similar theme, a parents’ group launched a recall campaign against all five trustees. And finally, this week, hundreds of teachers staged a sickout to protest West Ada’s plans for a blend of in-person and online instruction, forcing the schools to close for two days.

Angry parents. Nervous teachers. Impatient legislators. And if the public health experts are right, Idaho still hasn’t seen the worst of this wave of the coronavirus pandemic.

West Ada isn’t unique. Recall drives are also in the works in Pocatello-Chubbuck and Idaho Falls. And in a guest opinion this week, state superintendent Sherri Ybarra noted the “sharp disagreements” between some trustees, parents and educators.

In this same piece, Ybarra also was quick to say she cannot, and should not, tell districts what to do. (Which is partly accurate. The state’s current school reopening framework, released in July, places the decision with districts. In March, however, Ybarra and her State Board colleagues voted to close all K-12 schools.)

Elected but unpaid and untrained, trustees are familiar with making tough decisions. Their responsibilities are wide-ranging. They set district budgets. They decide whether to pursue bond issues for new buildings, or supplemental property tax levies to help pay the bills. They have to agree on teacher contracts — no small responsibility, when school districts are the largest employer in many small towns. They hire superintendents.

And certainly, trustees can find themselves in the middle of an emotional community debate — but often it’s for dropping an American Indian-themed nickname or redrawing school boundaries. In his eight years on the Boise school board, Rohn said the most controversial issue he’d faced came in 2017, when trustees considered moving up the start of the school year.

That, of course, was before 2020.

In August, as Boise reconsidered its reopening plan, trustees received more than 800 written comments from patrons: 432 supporting in-person learning, and 430 supporting online learning. It was clear to Rohn that he was facing not just an visceral issue, but a no-win decision. In his resignation letter a month later, he took a different tack from other trustees who clamored for local control. He chastised federal and state officials for punting on the issue and leaving the tough call to trustees.

Rohn isn’t alone in this sentiment.

Rohn isn’t alone in this sentiment.

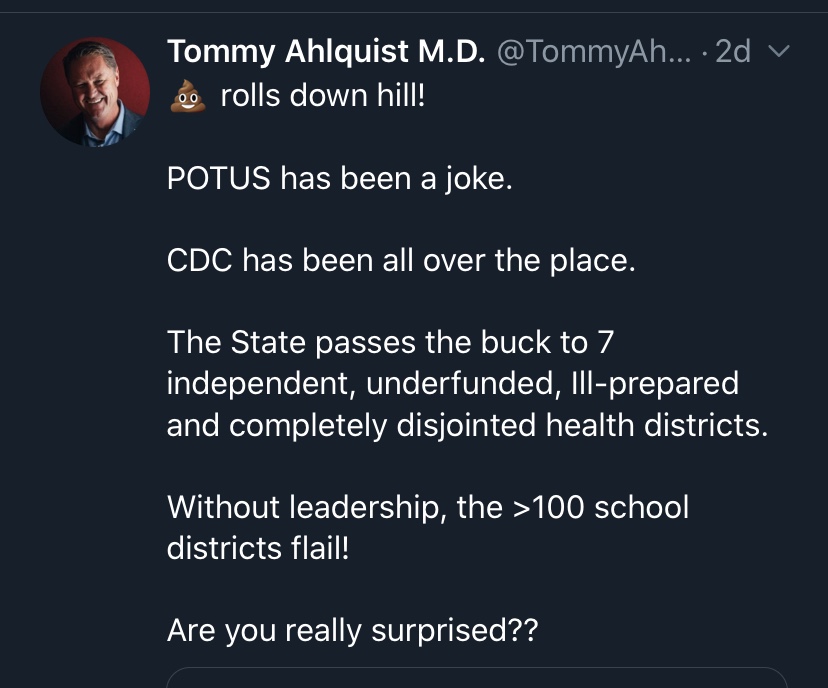

Tommy Ahlquist — a developer, doctor and 2018 GOP gubernatorial candidate — took fellow Republicans to task on Twitter this week. He called President Trump’s response to the pandemic a “joke,” and criticized state leaders for kicking the issue down to health districts and school districts.

“Without leadership, the (more than) 100 school districts flail!” he said.

Former West Ada trustee Mike Vuittonet is also sympathetic. He says he’d prefer a different approach to a hybrid schedule, saying parents and students might adjust better to a full week in school, followed by a full week of online coursework. But he also notes that trustees are caught in a political tempest, drowning in a deluge of data.

“It’s coming from everywhere,” Vuittonet said. “The problem is you don’t know what to hold onto, and what not to hold onto.”

After 18 years on the West Ada board, Vuittonet was voted out in November. But he says he opposes the current recall drive. Vuittonet was the one holdover from West Ada’s 2016 recall drive — when longtime Superintendent Linda Clark resigned, two trustees were voted out and two other trustees resigned before the election. In the process, he said, the district lost a lot of institutional memory.

A recall drive also raises a practical question: If voters boot trustees in West Ada, who would actually want their jobs? Only one of the district’s five trustees has won a contested race: Amy Johnson, the newest trustee, who ousted Vuittonet last year.

Even in the state’s largest school district, there aren’t exactly throngs of wannabe trustees standing in the wings. Many districts struggle to find anyone to run for the job. The aftereffects from the pandemic will only make that problem worse, said Quinn Perry, policy and government affairs director for the Idaho School Boards Association.

A localized reopening strategy seemed more straightforward in the spring, when some communities had only a handful of coronavirus cases. As the outbreak has taken hold across Idaho, she said, trustees have been left to make the politically sensitive decisions: crafting school calendars and sports schedules and dealing with pushback from “COVID deniers” who oppose shutdowns and face masks.

Some trustees call ISBA for advice. Others just call to vent.

“The sentiment is exhaustion and agony,” Perry said.

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.