Source: State Board of Education

The new data tell an old story.

One the state isn’t talking about much.

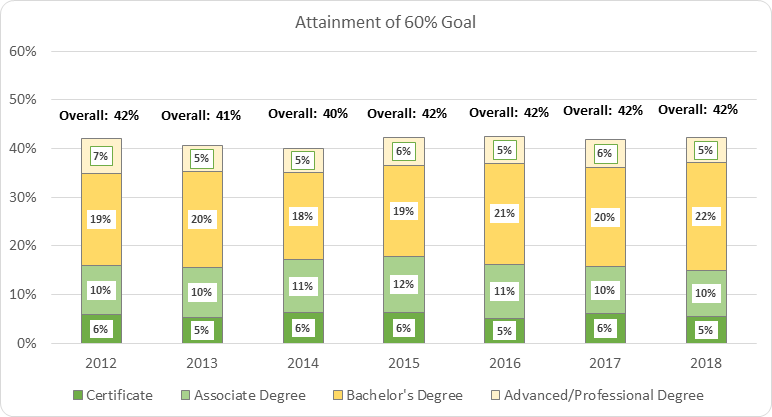

In 2018, Idaho made no progress toward its “60 percent” goal. Again. Only 42 percent of the state’s 25- to 34-year-olds held a college degree or professional certificate.

Same as 2017. And 2016. And 2015.

These are important numbers because state leaders have affixed so much importance to them.

The State Board launched the 60 percent goal in 2010. We have frequently called this the state’s centerpiece education goal, and for years, that was accurate.

Political, education and business leaders coalesced behind this ambitious goal and talked it up incessantly. The goal put a number to what they defined as an urgent need: preparing young people for a changing labor market. Former Gov. Butch Otter convened not one but two task forces to come up with recommendations to nudge Idaho closer to 60 percent. In his prior political life, as lieutenant governor, Brad Little pushed a nonbinding legislative resolution preaching the 60 percent gospel.

Now, as governor, Little frames the endgame differently. For example, he didn’t mention the 60 percent goal in his State of the State address in January. He talks instead about preparing high school graduates for college or a career.

But there are a lot of ways to measure progress toward college and career readiness. The number of high school students who take state-funded dual-credit classes. The “go-on rate:” the number of high school graduates who head to college. The number of students who receive the state’s Opportunity Scholarship.

The State Board’s latest Fact Book — a glossy education annual report of sorts — dutifully reports the dual credit, go-on and scholarship numbers. It doesn’t mention the 60 percent goal either.

State Board officials say they aren’t abandoning the 60 percent goal. The board isn’t happy with the latest numbers, President Debbie Critchfield said, but she doesn’t think the state should move the goalposts.

“I hesitate to just start wholesale replacing these things,” Critchfield said Thursday.

But postsecondary completion is a sticky metric. In its 2018 Fact Book, the State Board did devote one page to the 60 percent goal — and an attempt to explain Idaho’s perennial struggles.

“Idaho is a net exporter,” the report reads. “Overall, 54 percent of Idahoans age 25-34 who moved into the state in the last year had a postsecondary credential while 58 percent of those who moved out of the state in the last year had a postsecondary credential.”

The brain drain between Idaho and Washington was especially acute. Seventy percent of Idahoans who moved to Washington had a degree or certificate; only 50 percent of Idaho’s new arrivals from Washington held a degree or certificate.

So what does all this mean?

A lot of things, perhaps, that have nothing to do with education.

A young adult might have any number of reasons to move from Idaho to Seattle, Portland or California: a better career opportunity, a desire to check out life in a big city, and so on. By the same token, Idaho’s 42 percent completion rate might be, to a large extent, a statement on the state’s job market.

“(It’s) behavior that we can’t influence as a board,” State Board Executive Director Matt Freeman said.

Idaho didn’t develop its 60 percent goal in a vacuum. A decade ago, the State Board reacted to Georgetown University research, which concluded that the nation’s work force wasn’t ready to meet employers’ demands for skilled employees. This research — a “clarion call,” said Freeman — prompted many states to establish variations of a 60 percent goal. The Indianapolis-based Lumina Foundation, meanwhile, began promoting a national 60 percent goal.

As a result, it’s easy to place Idaho’s completion rate in a damning national context.

Lumina does its math differently, tracking all adults, not just 25- to 34-year-olds. Idaho’s 2018 completion rate came in at 41.9 percent — outpacing only Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Nevada and West Virginia. The national completion rate is 48.4 percent. (Lumina wants to see the nation hit the 60 percent threshold by 2025. Like Idaho’s 2025 target date, this seems far-fetched.)

Perhaps it’s no surprise that the State Board is emphasizing — and seeking — new metrics. The board has asked Idaho’s college and university presidents to come up with “production goals” for their institutions, Freeman said. Those goals, which could include metrics such as degrees awarded, could be set by summer. Critchfield wants to see the State Board align college performance goals with K-12 goals — which are already going through a makeover of their own.

Critchfield is encouraged, because she sees the state making progress in some areas. But after a decade of shooting for 60 percent, she acknowledges that a static 42 percent completion rate isn’t a good look.

“Sometimes it’s hit over our head that we’re not making improvements.”

Each week, Kevin Richert writes an analysis on education policy and education politics. Look for it every Thursday.