This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

In his frenetic first week back at the White House, President Donald Trump allowed immigration raids at schools, sidelined federal employees focused on diversity and ended civil rights investigations into book bans.

But the biggest education story of the week — one that could change public schools forever — broke late Friday afternoon at a building two miles away.

The U.S. Supreme Court, backed by the conservative supermajority Trump secured in his first term, agreed to hear an Oklahoma case over whether the law permits public dollars to flow to an explicitly religious charter school. A decision in favor of the first-of-its kind Catholic school could further entangle the government and religion, dramatically altering the historic balance between church and state.

“The stakes really couldn’t be higher,” said Derek Black, a law professor at the University of South Carolina. While there are Catholic schools that have converted into secular charters, St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School’s “ultimate goal,” according to its website, is “eternal salvation.”

“The issue,” Black said, “is whether a religious entity can operate a charter school that teaches religion as truth.”

Trump supports Christianity in the classroom and has vowed to bring prayer back to public schools. But he’s just the most recognizable face of a larger movement that has been building toward this moment — one that includes governors and state lawmakers, right-leaning think tanks and wealthy donors. Those donors have not only financed campaigns to seat conservative justices, but also helped fund the years of legal work that ultimately landed the school’s application before the high court.

Some evangelicals believe the courts have long misapplied Thomas Jefferson’s famous words about “a wall of separation between church and state.” Dismissed by most constitutional experts, this view holds that Jefferson’s aim was to keep the federal government from interfering with religious freedom — not to protect the government from the church.

The debate over the school will culminate in oral arguments before the Supreme Court in late April.

Governors in Texas, Oklahoma and Louisiana, who advocate for weaving the Bible into classroom instruction, have long awaited such a case. “Denying St. Isidore a charter solely because they’re religious is flat-out unconstitutional,” Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt posted on X. “This will be one of the most significant decisions of our lifetime.”

But his state’s GOP attorney general disagrees. Gentner Drummond’s office will argue that both state and federal laws clearly require charter schools to be non-sectarian. That view was summed up by American Federation of Teachers President Randi Weingarten, who said reversing the Oklahoma court’s decision “would drive a dagger into the very idea of public education and strike at the heart of our nation’s democratic foundations.”

One justice who won’t be involved in the decision is Trump’s most recent Supreme Court appointee. Justice Amy Coney Barrett recused herself from deliberating over whether to hear the case. While the court offered no explanation, Barrett is a longtime friend of Nicole Garnett, the Notre Dame University law professor who advised the Catholic Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa on the charter application. Garnett, who had no comment on Barrett’s recusal, also sits on the board of the Federalist Society, a conservative and libertarian legal organization that has influenced Trump and previous Republican presidents on judicial appointments.

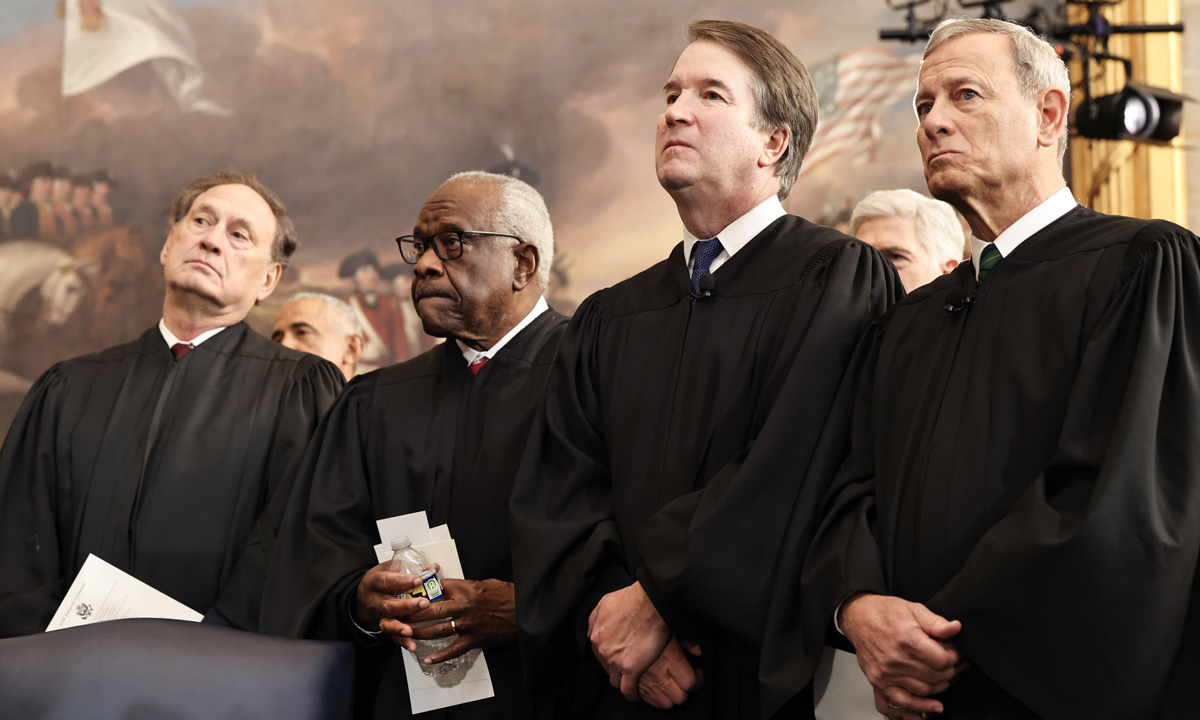

But attorneys for the school may not need Barrett’s vote. Four of the other conservative justices — Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch — have all voiced support for greater religious freedom. Over a decade ago, Thomas wrote an opinion suggesting states could establish their own Christian denominations. More recently, in 2022, Gorsuch referred to the “so-called” separation of church and state in a case over whether Boston should fly a Christian flag outside City Hall.

While Chief Justice John Roberts takes a more cautious approach to court precedents, he has sided with the conservative majority in all of its most recent church-state cases. Two of them, Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue and Carson v. Makin, focused on choice programs at religious schools.

Alliance Defending Freedom, which represents the state’s charter school board, draws on those cases to conclude that charter schools are inherently private organizations — not “state actors.” By keeping St. Isadore closed, the Alliance argues, Oklahoma is discriminating against religion and denying families more options.

“Oklahoma parents and children are better off with more educational choices, not fewer,” Jim Campbell, the Alliance’s chief legal counsel, said in a statement.

In a brief in support of the charter school, eight GOP-led states said that prohibiting the funding of religious charter schools would compromise their ability to award grants or contracts to other sectarian organizations, like orphanages and groups providing scholarships.

The National Alliance for Public Charter Schools dismissed that fear and said a charter is not “merely a grant program.”

“The charter school is a state-created public school under Oklahoma law, and its actions are state actions,” the organization wrote in its brief.

Black agreed, saying that the school’s argument “has no grounding in facts or law.”

The court’s decision to take the case left the law professor with an “enormous pit” in his stomach. Black worries the justices don’t fully understand the complexities of public education funding, particularly the differences between charters, vouchers and education savings accounts.

“That leads to either honest errors, misunderstandings or the ability of other people to lead you astray,” he said.

Experts say it’s hard to ignore the strides evangelical Republicans have made at elevating the importance of Christianity in the classroom.

Red states aren’t just passing voucher programs that allow parents to pay tuition at faith-based schools; they’re also incorporating Bible lessons into the curriculum. If the court rules in favor of the school, Preston Green, a University of Connecticut education and law professor, predicts religious organizations would suddenly “clamour” to open faith-based charters.

In addition to allowing public education funds to support a specific faith, a decision in favor of religious charters could also have a devastating financial impact on traditional districts fighting to prevent enrollment loss, Black said. Oklahoma already offers a tax credit scholarship program for school choice, but it doesn’t always cover the full tuition at a private school. Families who want their child to have a Christian education might be more likely to flock to a religious charter school where the cost is fully covered, he explained.

Robert Franklin, a former member of the state’s charter board, is already thinking about those ramifications. Like public school advocates in other red states, he’s concerned that expanding private school choice will hit rural schools the hardest and leave less funding for traditional schools.

“Oklahoma is a deeply red state,” he said. “I don’t think we have an appetite for raising taxes around here to support schools.”

Franklin has a unique vantage point on the constitutional dispute that began over two years ago. He voted against St. Isidore’s contract in 2023 and says he felt “vindicated” last year when the state’s high court struck it down. But he’s less confident the U.S. Supreme Court will rule the same way.

“It’s a tumultuous moment,” he said. “There are a lot of forces pulling the other direction.”