Fields of corn, onions and potatoes flanked the road as Genoveva Winkler drove the morning rounds.

“Welcome to my office,” she said, navigating the stretch from Interstate 84 toward New Plymouth.

As she drove, Winkler scanned the fields for porta-potties: a tell that workers were out and about.

“This is the hunting part,” she said.

Winkler is a regional coordinator for Idaho’s Migrant Education Program, a federally funded effort to help the children of migrant farmworkers succeed in school. Part of her job is training program staff on how to find families who qualify. Sometimes, she does that work herself.

Participation in Idaho’s Migrant Education Program has climbed significantly in the past few years, following a period of declining enrollment across the state. While a number of factors could play into that enrollment jump, state officials say one thing is certain: employees have stepped up their recruitment with boots-on-the-ground effort.

“Our family liaisons, who find the kids, cannot spend all their time behind a desk,” said Sarah Seamount, coordinator of the Migrant Education Program for the State Department of Education. “They have to get out there into the community.”

That’s why, on a hot Wednesday morning in July, Winkler tiptoed between pepper plants in a field, making her way toward a line of workers weeding crops.

“We’re from the schools. This is help for the kids — like those young ones,” she told the workers in Spanish, gesturing to two teenage boys working with the group. “If they qualify for the program, we can help them with school resources.”

After a quick introduction, Winkler taped a flyer with her phone number to the group’s bathroom and left Gatorades for the workers at the end of the rows.

Winkler drove the western border of Idaho’s Treasure Valley that day. She talked with dairy workers on their breaks in New Plymouth and left a trail of flyers for the program from Fruitland to Parma.

“That’s how I spend my summer — looking for people,” Winkler said as she drove.

By the numbers: More students means more funding

Children qualify for the Migrant Education program if they have a parent or guardian who works in agriculture and have had to move school districts within the past three years. The program’s goal is to help kids succeed in school, even if they move frequently for agricultural work.

Decades ago, the number of migrant students in Idaho was far higher than it is today. But, by 2016 Idaho districts had recorded a major decline in their numbers — up to 44 percent for some districts — Idaho Education News reported. Machinery that lessened the need for farm labor played a roll in that drop, Seamount said, and for a period of time, the state’s emphasis on recruiting migrant students waned.

When Seamount arrived at the Idaho Department of Education four years ago, she and former program director Christina Nava studied the declining enrollment.

“Quite honestly, it was alarming,” Seamount said. “We knew (the data) represented we were not identifying every child.”

That meant some kids weren’t getting services — and presented a catch-22 for program funding, since program funding is based on participation.

“If you have too few kids, eventually it becomes much harder to find more kids, because you don’t have the funding to pay staff to be looking,” Seamount said.

With that challenge looming, the state kicked up its efforts on recruitment. Seamount created a map of Idaho’s agricultural areas and beefed up recruitment training. Today, liaisons for the program are expected to participate in community events, build relationships with farmers and go find workers and their families.

In the past three years, student participation has climbed steadily. As of July, 4, 882 students had participated in the program during the 2018-2019 school year.

.

Source: Idaho State Department of Education

Enrollment changes have been drastic in some districts. Caldwell and Nampa have seen funding projections increase about 50 percent since the 17-18 school year. Smaller districts, like Kimberly and Mountain Home, have projected increases over 150 percent.

The extra money will help Nampa start a migrant student preschool this fall. Kimberly is considering using the money to start a migrant summer school.

Benefits of migrant education programs

Students enrolled in migrant education programs can access benefits like school supplies, tutoring and summer school. Program liaisons can refer families to health care organizations and food banks, accompany parents to school meetings and help them navigate school systems.

“We try to provide everything, academically, that a child may need,” Winkler said.

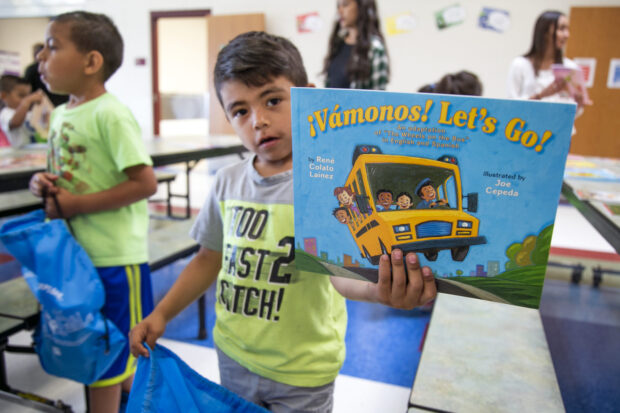

At a migrant summer school program in Nampa this summer, Donaldo “DJ” Jimenez, helped his classmates during reading time.

His third-grade group read paragraphs aloud, then discussed them in English. Afterward, Jimenez reenacted scenes in Spanish.

Jimenez, who has Elvis-styled hair and a playful showmanship to match, has attended Nampa’s Migrant Education Program summer school for two years.

“When I came here, I just talked Spanish,” Jimenez said. With help from the program, he said: “I learned English.”

His classroom interpretations of the book helped the other students follow suit.

Down a hallway at New Horizons Elementary, Ashley Estrada and other middle schoolers made slime out of glue, hair gel and contact solution.

Estrada said resources in the migrant education program have helped her with math. She once struggled with division, but educators in the program have helped her improve.

“They showed me an easier way of remembering it,” Estrada said. “I got the hang of it. When I took a test at my regular school I got a B.”

Gisel Holdcroft, a family liaison for Nampa’s migrant education program, knows that the benefits of summer school extend beyond academic and language skills. She was a migratory student herself. Frequent moves don’t just impact a students’ academics, Holdcroft said, they can also make it hard for a kid to feel connected in a school setting.

“These kiddos, with their high mobility, they don’t get used to a specific teacher or specific friends because they know they’re going to leave again,” she said. “They might feel out of place. When we come to summer school, we are all in the same boat.”

The migrant education program also helps students make the transition from high school to the world beyond. This summer, three dozen high school students attended a Migrant Student Leadership Institute at Boise State University this summer, where they toured businesses, worked on college entrance essays and stayed in the dorms.

Maria De La Cruz Aquino, a 17-year-old from Twin Falls, said the camp helped her learn about scholarships. Aquino wants to be a nurse, a career sparked by an enfermera who took care of her father after he was in an accident. She’s hoping to attend Boise State or the College of Southern Idaho.

Aquino wasn’t sure whether she would attend the camp initially. Leaving Twin Falls meant she wouldn’t be around to help take care of her younger siblings. By the end of the week, she was glad she made the trip.

“This is for my future,” Aquino said. “So that I have opportunities.”