Thursday’s formal vote was quick and unanimous: The state Public Charter School Commission admitted it violated Idaho’s open meeting law during a contentious closed-door meeting in April.

But the vote came after a tense one-hour public comment period, when several charter school advocates scolded the commission for breaking the law and violating their trust.

“Any trust I had in being treated fairly was already shaky,” said Kelly Edginton, head of school at Idaho Virtual Academy. “(Now) that trust is zero.”

The commission’s Thursday morning meeting came one week after Attorney General Lawrence Wasden’s office said the commission likely violated the open meetings law during a wide-ranging two-hour executive session on April 11.

But the meeting also came weeks into a simmering controversy that started in June, when the commission inadvertently released a recording of the meeting. Some charter advocates have blasted the commission for maligning student performance at several schools, and discussing the prospects of closing schools or the politics of denying a renewal of a school charter.

On Thursday, several charter administrators said they were blindsided, and said the commission took their test scores out of context. But two charter school lobbyists said April’s meeting was symptomatic of larger problems.

Teresa Molitor, a former board member at Heritage Academy in Jerome, said she was not surprised to listen to the recording and hear commissioners denigrate the school’s test scores.

“I’ve heard the same disdain and condescension from you and your staff for many years,” she said.

Suzanne Budge worked on the 2004 law creating the state charter commission. The main objective was to create a panel that could authorize charter schools — an alternative to local school districts that were sometimes reluctant to take on the authorizing role.

“The commission has strayed very, very far from its original mission,” she said.

The seven-member commission authorizes nearly three-fourths of Idaho’s 56 charter schools.

But some charter administrators and advocates came to the commission’s defense Thursday. They said the panel has an important role in monitoring student performance and charter school finances — even if that means pushing back against the schools under its bailiwick.

“We needed that feedback to get to where we are today,” said Melissa Andersen, secondary school administrator at North Star Charter School in Eagle.

Meridian’s Compass Public Charter School was one of the first schools the commission authorized. The commission quickly put the school on notice over financial issues, and it was a frustrating time, administrator Kelly Trudeau said Thursday.

“The commission was just doing their job. It was not personal,” said Trudeau, who praised the commission for juggling the interests of students, parents and staff.

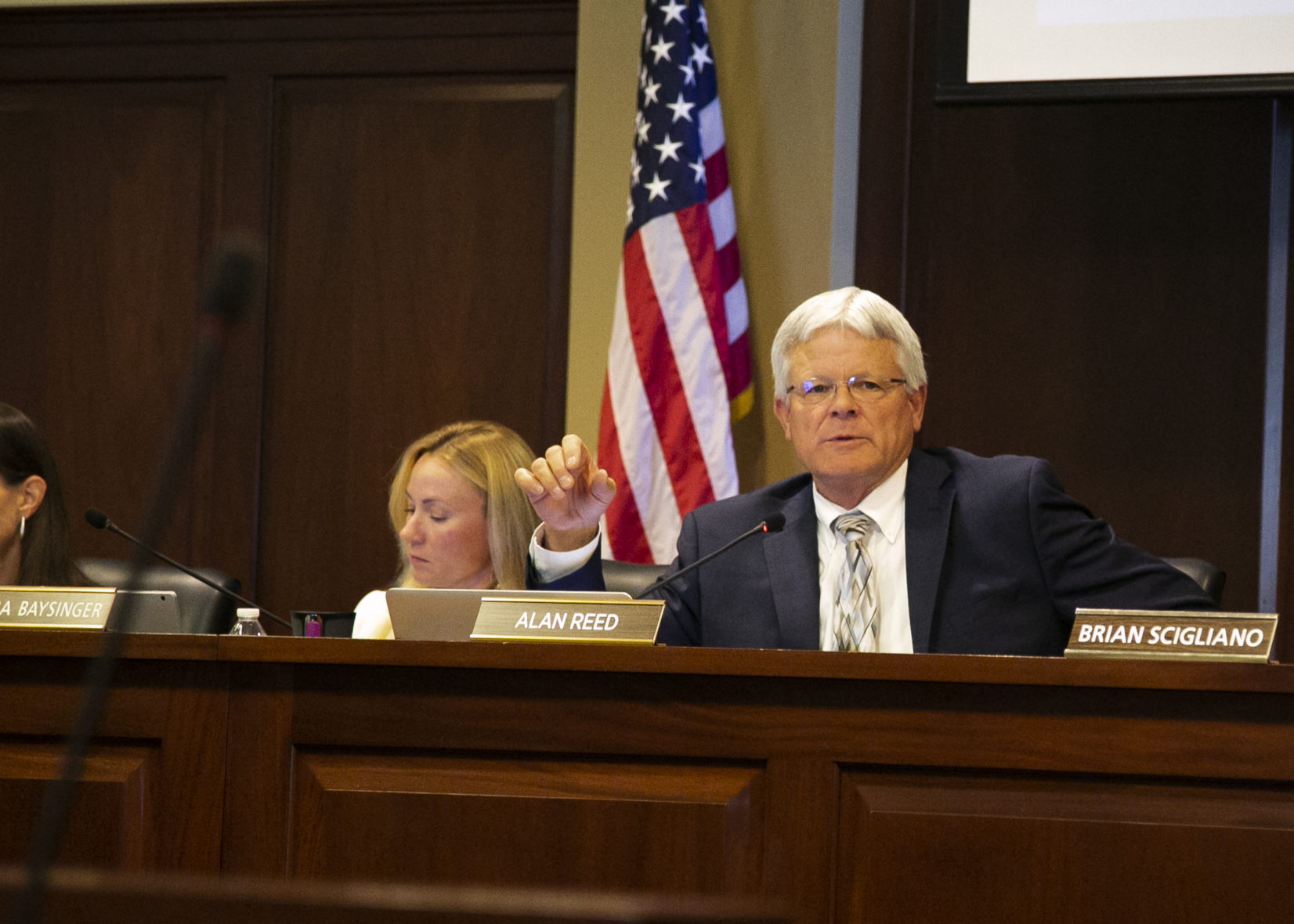

Thursday’s meeting was at times awkward. Before opening the floor for public comments, commission Chairman Alan Reed offered a mea culpa. “This is an interesting meeting, humbling meeting, to say the least.”

At another point, Reed reminded speakers to talk clearly into a microphone, with an attempt at humor. “We love these recordings, you know.”

Several legal issues plagued the April 11 executive session — but one was what Wasden’s office described as “drift.” During the course of the two hours, the focus shifted from confidential student data, the stated purpose for a closed-door meeting, to topics that should have been discussed in an open session.

Commissioners did not debate that point, or any findings from Wasden’s report. Voting unanimously, the commission admitted to violating the law, as Wasden’s office recommended a week ago.

The commission then went into an open meetings training session, attended by Wasden and conducted by one of his deputies, Brian Kane. The training, and the commission’s vote, is a step toward restoring the public trust.

“I understand what it means for you to come forth … and admit your missteps,” Kane said.