More than 100 elementary students, clad in red, white and blue outfits, shuffled in from recess at American Heritage Charter School. Their color-coordinated clothes ranged from navy blue dress slacks and white collared shirts for boys to plaid jumpers and red stockings for girls.

No flip-flops. No hoodies.

“We treat our dress code as a big deal here,” said Deby Infanger, the Idaho Falls-based charter school’s founder and board chairman. “We feel that it helps students respect themselves and see each other more as equals.”

A strict- and patriotic-themed dress code is just one way educators at American Heritage differentiate their school from others in East Idaho. It’s all part of an effort to mingle old-fashioned values with a more modern, technologically driven curriculum — one with American flags lining the hallways, a laptop in every student’s hand and PowerPoint lessons laced with slides emphasizing the attributes of American presidents past.

A hodgepodge of publicly funded charter schools — often started by parents and each touting their own unique educational approach — have been popping up throughout Idaho for nearly two decades now. Supporters say more charter schools provide a wider array of educational options for kids, and they point to some of the state’s highest standardized test scores and unique learning frameworks as evidence of success.

But many Idaho charters also are among the state’s lowest-performing schools. And though public opinion surrounding their effectiveness varies greatly, some critics and traditional K-12 educators question the prudence of charter schools altogether, citing a lack of diversity compared to Idaho’s traditional schools and funding repercussions in the wake of their expansion.

“If Idaho is struggling to fund its traditional schools, why area we adding more?” said Madison School District superintendent and ardent charter school opponent Geoff Thomas.

But even as the rise of charter schools stirs debate over student performance and school choice, most Idahoans say they support them — though many admit not knowing much about them. In the 2017 “People’s Perspective,” a public opinion poll conducted by Idaho Education News, 54 percent of Idahoans who report a charter school in their area think they outperform regular public schools. But just 34 percent of those polled said they knew a “great deal” or “quite a bit” about Idaho’s charter schools.

Their rise and current numbers

On Sept. 7, 1999, in a vacant office building in downtown Boise, one of Idaho’s first public charter schools that’s still in operation opened its doors.

The school enrolled 112 students and was hatched by a Boise School District elementary principal named Darrel Burbank, who started posing a simple question to colleagues: “What would a ‘dream’ school look like?”

A year earlier, the Legislature passed a law allowing any group to start a public charter school or convert an existing school into one, provided petitioners met state-mandated, startup criteria, including gathering enough local signatures and obtaining approval from one of the state’s two official charter school authorizers: one of Idaho’s 115 public school districts or the Idaho Public Charter School Commission (PCSC).

The Boise district initially denied Burbank’s petition for a new school centered on expeditionary learning, citing a lack of public interest at the time. But Burbank didn’t give up. After he and several like-minded parents and educators began exploring other avenues for getting the school off the ground, Boise trustees granted authorization.

Anser Charter School was born, and calls for similarly unique schools began rumbling across the state. By 2002, 10 charter schools had opened their doors in various parts of northern, western and eastern Idaho. That number tripled by 2008, and has since settled at 52.

Anser served about 300 of the 21,351 kids that enrolled in charter schools throughout the state last school year. In 2016-17, 7.6 percent of Idaho’s 277,335 K-12 students attended charter schools.

Idaho’s highest — and lowest — performing schools

Over the years, charter school authorization via school district has become less common in Idaho. Since 1998, just 15 of the state’s 52 charter schools have gained authorization through a district. The PCSC has, meanwhile, granted authorization and provides oversight to Idaho’s remaining 37 charter schools.

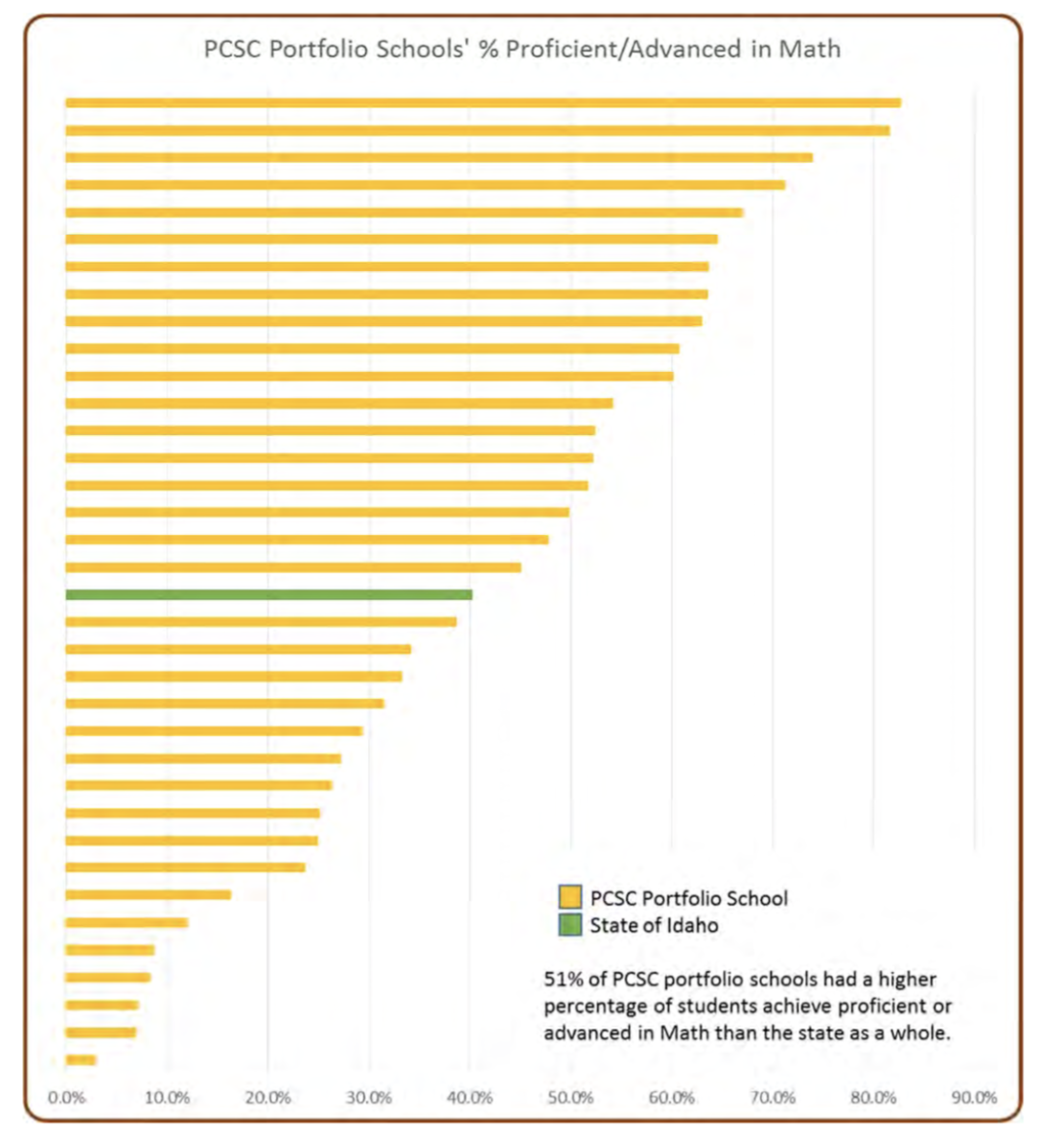

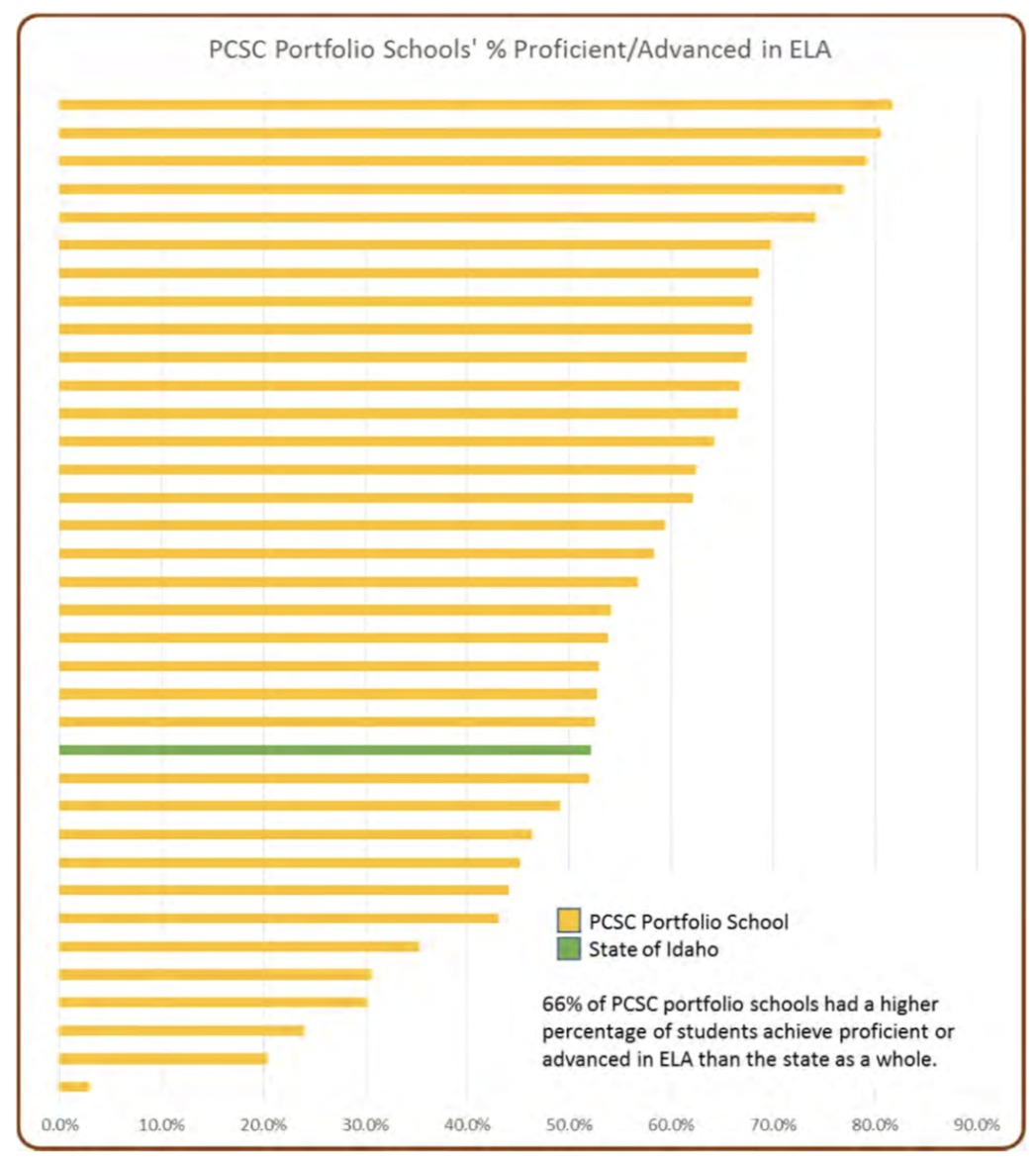

Many of these PCSC-sanctioned charters have evolved into some of the state’s top-performing schools. According to an annual report presented to the State Board of Education last year, 51 percent of these charters yielded a higher percentage of students achieving proficient or advanced scores in the math portion of the 2015 ISATs than students throughout the rest of the state. Sixty-six percent had a higher percentage of students achieving proficient or advanced scores on the English language arts portion of the test.

But those percentages also highlight a number of charter schools performing well below state averages — nearly half in math and 34 percent in ELA. And just as several schools yielded proficient and advanced scores markedly higher than the state average in 2015, others yielded scores markedly lower — on both portions of the test.

For example, the four top-performing PCSC charters exceeded the state’s proficient and advanced average on the math portion of the ISAT by more than 30 percentage points. The five lowest-performing PCSC schools each trailed the state average by more than 30 percentage points.

The ELA portion of the test doesn’t reflect such a dramatic spread, but still illustrates a wide disparity. For example, the five top-performing charter schools garnered scores at least 20 percentage points higher than the state average, but the five lowest-performing schools produced scores at least 20 percentage points lower than the state average.

Charters provide a wider array of school options

The disparity in scores represents just one aspect of the growing pains public charter schools face, said Terry Ryan, CEO of Bluum, a Boise nonprofit that supports school innovation.

“Failure is part of all this,” Ryan said. “But a school — any school — that is persistently low academically should close. We also need to ask other questions, like are they showing growth and where were the kids, academically, when they first came into the building?”

Ryan reiterated that the appeal of many charters lies not so much in test scores, but in their ability to provide a wider array of educational options for Idaho families. He pointed to a new charter school in the Upper Carmen area, a rural ranching community in central Idaho that once had its own one-room school, but lost it through consolidation. Idaho’s charter school law enabled locals to open Upper Carmen K–8 school in 2005, which now serves about 85 students in multi-age classrooms.

Parent Ashley Howell agrees that despite some struggles, charter schools have earned their place in Idaho. Her four children have bounced between a regular public school district and three charter schools in the Blackfoot area for nine years now.

The wider array of options spurred by charters has helped her kids meet different needs at different times, Howell said. Sometimes, a charter school’s smaller class sizes enticed her kids. At other times, the perceived social advantages tied to a larger, regular school were the deciding factor.

“I’m just a big believer in school choice — and that competition drives success,” Howell said.

But others say the wider array of educational options isn’t being presented equally to all Idahoans, especially minorities and the poor. A 2015 report presented to the State Board of Education revealed that Idaho charters lack diversity compared to Idaho’s regular public schools. And an Idaho Education News analysis revealed that many of these same schools don’t provide free-and-reduced lunch and busing services to students.

“Should we be using public money to fund schools that don’t appear to be serving all students?” said Sam Byrd, director of the Centro de Comunidad y Justicia (Center for Community and Justice), a Boise nonprofit aimed at improving the education, economic, and social status of Latinos in Idaho.

Greater competition spurred by charter schools is also something Blackfoot School District superintendent Brian Kress has become familiar with in recent years — and not so much in a good way. The rise of three nearby charter schools has encouraged Kress and fellow district educators to reflect on ways to improve, but the competition leads to enrollment and funding challenges.

In 2013, 4,290 students enrolled in the Blackfoot district. That number fell to 4,069 in 2014 and to 3,922 in 2015 — due, in part, to increased enrollment of nearby charters. In a state where school funding is based primarily on average daily attendance, Blackfoot’s loss of students ultimately led to a loss of state dollars. Kress acknowledged that his schools didn’t shoulder this loss throughout the entire school year, but the unexpected enrollment declines came after the district had already entered into salary agreements with its teachers.

By the time the school year started, Kress said, the district had more teachers than it needed and had to pay one to take an early retirement.

“I think it’s fine if people think a charter school will work better for their kids,” Kress said, “But there should be a grace period for negotiations in districts that are losing more kids than they might otherwise have expected.”

For more reading:

- Compare data between charter and traditional schools at IdahoEdTrends.org

- Find out what Idahoans think of their public education system at the People’s Perspective survey.

- Read more about the lack of diversity in many of Idaho’s charter schools.

Disclosure: The People’s Perspective survey and Idaho Education News are funded by the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation.