EDITOR’S NOTE: Eleven Idaho schools are launching an experiment this fall. They are using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools. This is the 11th of a series of stories on the grant recipients.

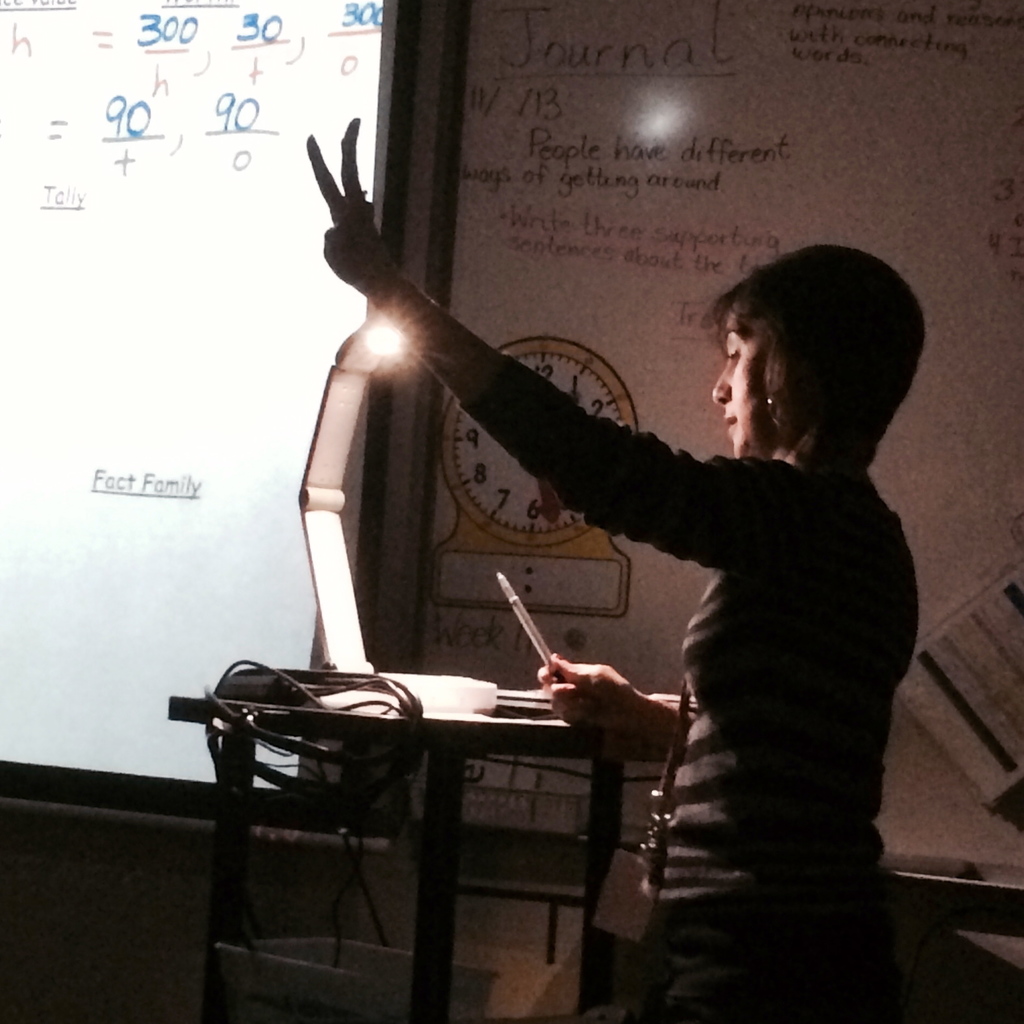

In Susan Luke’s classroom, second-graders sit on the floor at the front of the class, legs folded, for a high-tech story time. Luke reads the class “Beauty and the Beast,” pages projected onto a large whiteboard.

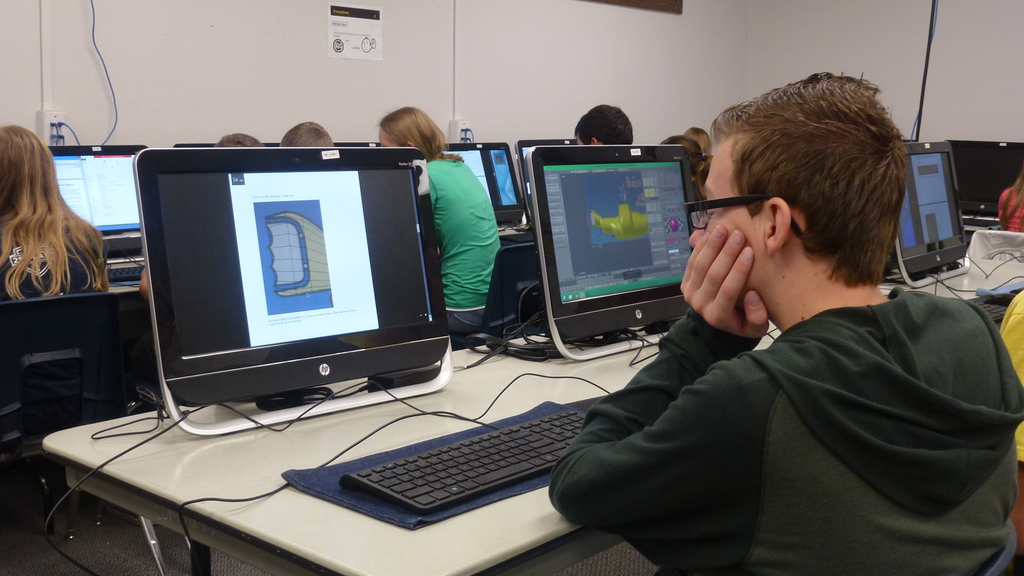

In the computer lab, sixth-graders use a new bank of desktop computers to design three-dimensional submarines.

But in that same lab, iPads sit on long table. Unused by high schoolers, at least for the time being.

In Meridian’s Compass Public Charter School, new technology is rolling out in the classrooms, in fits and starts. But that suits school IT coordinator Greg Cordero just fine. He wants teachers to take a four-year approach to integrating technology into the charter school: to take gradual bites out of the elephant.

“There is no pressure,” he said last week.

An incremental approach

Some of the state’s 11 technology pilot schools have very specific academic goals: improved test scores or bridging learning gaps between some student groups. Not so in Compass. Like all Idaho schools, Compass is preparing for the transition that comes with the new Idaho Core Standards and its new testing regime. But as a five-star school in the state’s most recent star ratings, the school made its academic record a selling point in its grant application.

“With the intent of the technology pilot grant being the development of a scalable project that can be disseminated to other districts in the state, a more effective awardee for this grant could be a school that has a record of demonstrated success such as Compass,” Compass said in its successful application for a $180,000 grant.

Cordero is applying a tech rollout strategy known as SAMR. In a milieu that lends itself to acronyms, SAMR stands for substitution, augmentation, modification and redefinition.

This year, the focus is on substitution: working some of the $180,000 in new technology into the everyday classroom routine. That can mean displaying a worksheet on a whiteboard, using one of the school’s new “dock cams,” instead of handing out sheets.

In augmentation, that same worksheet is delivered to a student learning device. In modification, students receive a worksheet in a form they can edit and annotate. Only then, in year four, comes the redefinition of learning.

Some teachers are plowing ahead already, into the augmentation phase. Some more seasoned teachers are moving a little more slowly. “But they’re trying,” Cordero said.

A technology microcosm

Compass — a converted church on the western fringe of suburban Meridian, serving 580 students — provides a microcosm for rolling out technology across a K-12 district.

Cordero downplays the challenge of deploying technology in a K-12 school — “It’s school to us, no matter the grade” — but the approaches will vary considerably. The ninth- through 12th-graders will get a chance to pilot one-to-one technology experience, with personal iPad minis that they can take home. The lower grades will have access to iPad minis, but sporadically: the school has three groups of 30 that classrooms will use on a rotating basis.

Then there’s the challenge of fusing technology to a grade school, middle school or high school curriculum. Most 11th and 12th graders at Compass take dual credit courses through the College of Western Idaho, and the high school curriculum is a bit more rigid; both factors will complicate a technology rollout, Cordero said.

A centerpiece of the Compass plan gives teachers a lead role in refining the use of technology. The school is assembling a technology task force — including teachers to represent the high school, middle school and grade school. It will be the task force’s job to figure out which learning apps work best in each grade level, and in specific disciplines, and to make sure that the technology program doesn’t interfere with the adjustment to the new Idaho Core Standards.

“This group will serve as our teacher leaders available to train and support the teaching team at their school levels,” Compass says in its technology grant application.

One to one — eventually

The idea behind the $3 million in technology pilot grants, awarded July 1, was to put the money into schools’ hands in early summer, so recipients could launch their projects at the start of the school year.

That hasn’t been the case with all the pilot schools, and Compass is a good example. The high school iPad rollout is on hold, and it’s unclear when students will get their devices. Compass is waiting on another state technology initiative: a controversial contract that will hook up most of the state’s high schools and junior high schools with state-funded WiFi systems. When the new WiFi network is installed, students will get their tablets.

And then comes the central challenge: teaching high school students to see the tablets not as toys, but as tools.

Taking the long view, Cordero says that may be less of an issue in time. Exposed to iPad learning in the lower grades, future high schoolers will enter a one-to-one program ready to tap the tablets’ potential. But in the short run, it’s about getting students to rethink their approach.

“They’ve used it in a different capacity,” he said. “It’s a little bit challenging, I’m finding, but we will get through this.”

More stories about the 11 Idaho schools using $3 million in state grants to try out methods of using technology in the schools:

- A schoolwide Chromebooks project at Kuna Middle School.

- A career-oriented laptop pilot at Middleton High School.

- An attempt to reverse achievement gaps at Parma Middle School.

- A writing emphasis at Weiser’s Park Intermediate School.

- A collaborative learning effort at Meridian’s Discovery Elementary School.

- A student-led iPad rollout at McCall-Donnelly High School.

- An effort to bridge geographic gaps at the Idaho Distance Education Academy.

- A Proposition 3 lookalike at Sugar Salem High School.

- Teachers and students team up to rollout iPads at Dayton’s Beutler Middle School.

- A big-screen vision at Moscow Middle School.