Holly Jo Shea wanted to work from home after the coronavirus closed St. Maries Middle School, where she teaches math and science.

She’s got two elementary school-aged children, one of whom has asthma, and her husband works as a plumber. As COVID-19 arrived in the state, her family tried to self-isolate. They didn’t visit family or friends, trying to “eliminate exposure” outside the risk they faced when Shea’s husband went to work.

Then, on April 6, Shea was called back to work. Teachers, who are considered essential workers, are exempt from Gov. Brad Little’s stay-at-home order, and St. Maries administration asked staff to come into the school buildings to assemble paper packets for students with no internet access. At that point, there hadn’t been a single case of COVID-19 in St. Maries, or in Benewah County, where the school is located.

But Shea was worried about her son with asthma. She didn’t want to send him to a daycare with other kids, and she didn’t qualify for a federal law that would let her stay home. Shea ended up asking relatives to watch her kids during the day, breaking the quarantine her family had tried to self-impose.

“I was very scared and frustrated when we first had to come back,” Shea said. “We had been practicing social distancing and we were basically forced to not practice social distancing.”

Shea’s fears and frustration over returning to work foreshadows the tension many educators will grapple with next fall, when schools resume in-person schedules in one format or another. Teachers across the nation say they’re hesitant to return to classrooms, and up to 20 percent say they’re unlikely to teach next fall because of coronavirus concerns, a USA Today poll found.

Idaho school districts must identify and plan for vulnerable students and staff before they can open their doors, according to requirements from the State Board of Education. But, the question of how districts will balance contractual obligations with the health and safety of staff members is one that many leaders are still working through.

“How do you handle someone who is perhaps in a category that makes their risk factors greater than someone else, or perhaps they live with someone?” State Board of Education president Debbie Critchfield said. “School districts are wading through these waters.”

Legal considerations

Teachers — and workers across many industries — who are sick, caring for a sick person, or who have been ordered to self-isolate can stay home on limited paid leave guaranteed by the federal government.

The Families First Coronavirus Response Act makes some employees eligible for up to 80 hours of leave (in addition to what their school district provides) if they are sick with coronavirus or caring for someone who is sick. An employee can also qualify for up to 12 weeks of leave if they have no childcare because of COVID-19.

For teachers who would like to stay home out of an abundance of caution, those protections don’t always apply.

“If they’re not feeling comfortable about coming back, that just isn’t a cause for not coming to work,” said Karen Echeverria, director of the Idaho school Boards Association. (Read more from the ISBA on the Families First Act, here).

Paul Stark, general council for Idaho’s teachers union the Idaho Education Association, says a set of Idaho statutes that govern workplace safety could also apply. The rules require that a workplace be safe from life threatening hazards and that employers train their staff on how to stay safe.

“An individual is entitled to a work place where they do not unduly risk harm to themselves. This is a big issue, certainly, now with COVID-19,” Stark said. “There are conditions that can be met to help ensure this.”

Districts, teachers, weigh different approaches

This spring, about 10 percent of Marc Gee’s staff in the Preston School district said they didn’t feel comfortable coming into school buildings due to the threat of the novel coronavirus.

“Everybody was willing to give each other a pass this spring with those kinds of decisions,” Gee said. Then schools closed, and the expectation was that teachers would work from home.

Those equations could get more difficult this fall, particularly if staff prefer to stay home while students return to the building.

He’s willing to make it work.

“I don’t believe that teachers are deliberately trying to get out of work. They’re trying to balance that responsibility they have to teach kids with the responsibility they have to watch over themselves and their families,” Gee said. “This is a hard decision for the teacher to make, as well as the district. A little understanding goes a long way in those situations.”

The Preston district doesn’t have a concrete plan for vulnerable teachers yet, Gee said, but he’s considered scenarios like letting teachers instruct classes remotely while a substitute oversees students. Another possibility would be letting teachers and students who are homebound work remotely together.

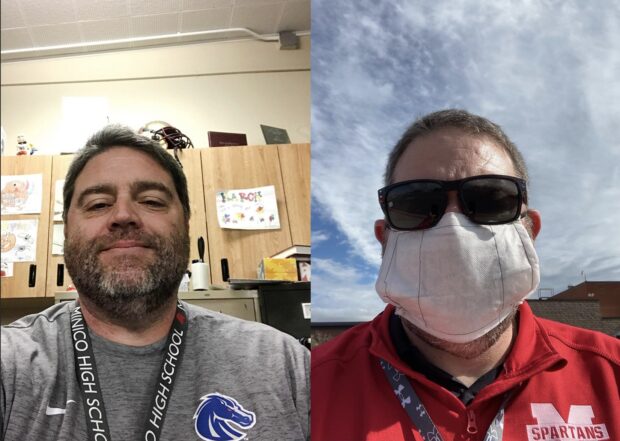

In the Minidoka School District, teacher Tim Behunin would like to see his school district require masks.

Behunin, 50, has diabetes, a condition that can complicate the impact of the coronavirus were he to catch the virus.

Behunin has been coming into his high school classroom this spring — wearing his mask — and he says he’s willing to do whatever his district asks of him in the fall. But he’d like to see best-practices like social distancing and mask-wearing required and enforced if students return to Minico High.

“The writing is on the wall that we’re going to be back in the building. I can accept that, but what’s going to be the management model?” Behunin said. “I think masks will be the critical element. Whether we like wearing them or not, we’ve got to have them on.”

Masks and gloves are optional for teachers coming into buildings in St. Maries, where Shea and her colleagues have two more weeks of work before summer break.

Superintendent Alicia Holthaus says the district disinfects high-touch parts of school buildings daily, and asks teachers to distance and limit how many people are in a classroom.

“I would not have them here if I didn’t believe they were safe,” Holthaus said.

As COVID-19 starts to circulate in Benewah County, the district is still uncertain about its plans for the fall. The Panhandle Health District confirmed the county’s first case of the virus at the end of May. By June 4, health officials said the virus was being transmitted through community spread.

Holthaus is holding out hope that buildings can open as usual next fall. But depending on the progression of the virus, schools might open some kind of modified schedule instead. Worst case, she said, the district would continue to rely on paper packets.

Shea is hoping her district plays it safe, like she did. As doctors have come to learn more about the virus, she said, they’ve learned asthma is less of a risk than she first thought. That’s a relief for Shea’s family now — but she doesn’t regret being cautious.

If community spread of coronavirus starts to happen in the town of St. Maries, Shea thinks school buildings should close.

“I know this is an unknown for so many different people,” Shea said. “It’s just so unknown that it’s not worth the risk.”