IDAHO FALLS — College-and-career advisor Natalie Black is used to hearing middle schoolers feign dislike for Legos.

“They’ll act too cool to play with them, but they usually love it,” said Black, who dumped a jumbo-sized set of the plastic building blocks onto the floor of a Taylorview Middle School classroom.

Legos are one way the Idaho Falls high school college-and-career advisor gets local eighth graders engaged in an activity typically reserved for high schoolers: college-and-career advising.

Idaho Falls is one of several Idaho districts to start providing college-and-career advising for middle schoolers in recent years.

Educators and state education leaders attribute the practice largely to Idaho’s emphasis on postsecondary education. For years, the state has tried desperately to boost its college go-on and completion rates. Advanced Opportunities, including state-funded dual-credit courses for high schoolers, have been a key part of the push.

Increased college coursework for high schoolers has fueled the need for kids to start thinking about life after high school before they get to high school, acknowledged State Board of Education College and Career Manager Byron Yankey, who pointed to college-and-career advising efforts for middle schoolers in the Idaho Falls, Madison, Kuna and Camas County school districts.

Efforts and techniques vary from district to district, Yankey said, with some focusing more on eighth graders and at least one, Camas County, including sixth graders in its efforts.

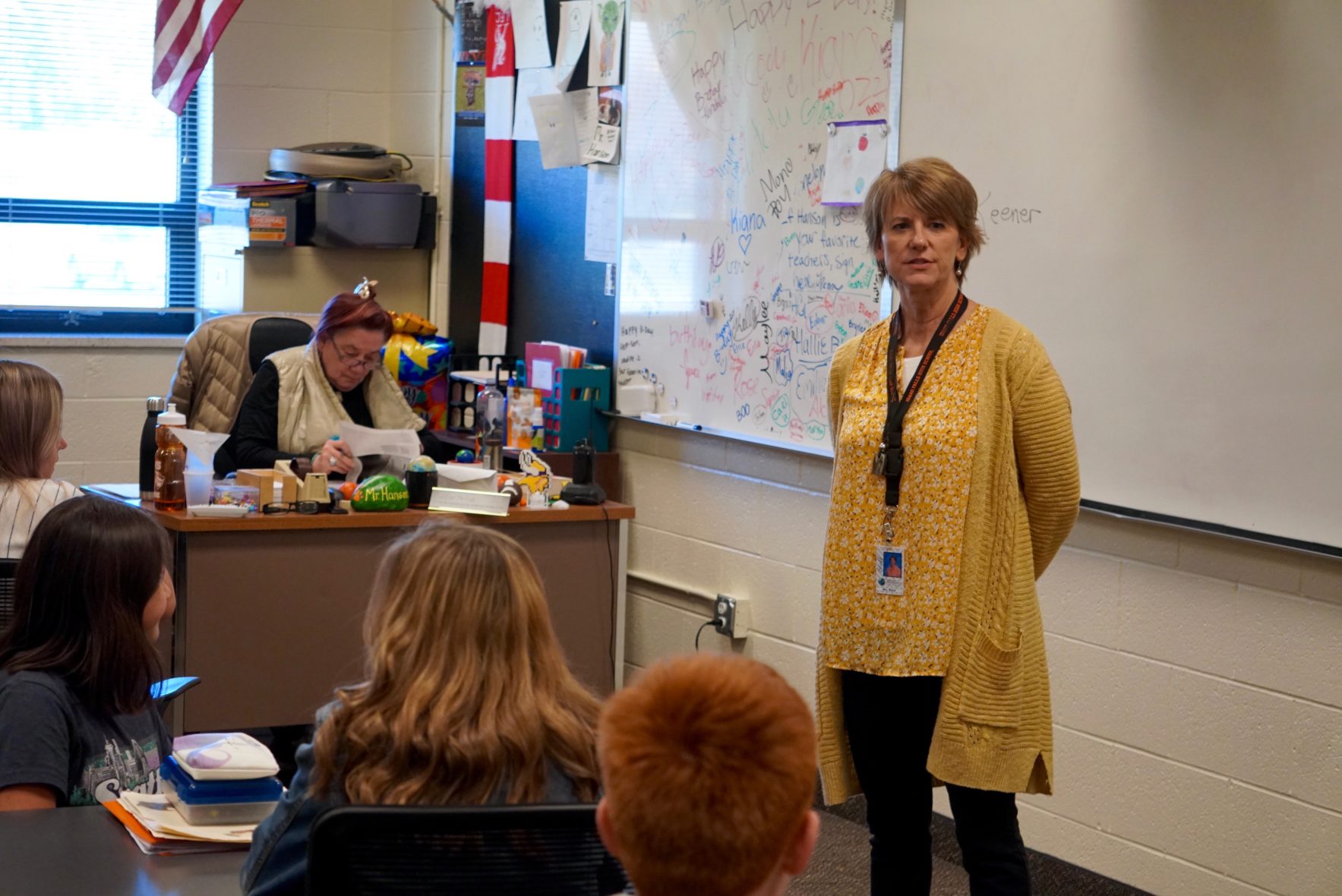

On Tuesday, Black left Idaho Falls High School to deliver her first advising session of the school year to a classroom of middle schoolers at Taylorview.

Connecting the youngsters with career concepts often demands more of a hands-on approach, she said.

That’s where Legos come in.

Black placed students into groups of five and asked them to construct a simple design of their choice using the Legos available to them. Afterward, each group coached a blindfolded student through the process of replicating their design.

Handing Legos to the blindfolded student is against the rules. Students can only explain which blocks to grab and how the blindfolded student should assemble them.

“Move your left hand forward,” said one student.

“Yes, grab that piece,” said another.

The assignment is an exercise in developing the kind of communication skills needed in the modern workplace, Black said.

“Imagine your co-worker asks you to grab a certain tool,” Black told the group. “Can you get it based on what they’ve said, or do you need more information?”

The exercise is also an example of college-and-career advising tailored for a younger audience, Black added.

“We focus a lot on things like developing soft skills for the workplace,” she said, as opposed to more specific questions related to a particular career path.

Idaho Falls middle schoolers are also more limited than their high school counterparts in their exposure to college-and-career advising. By the end of the school year, Black’s rounds to the district’s two middle schools will add up to just two advising sessions per student. Sessions take place during shortened 30-minute class periods typically devoted to study time.

The Lego activity usually constitutes the entire first session. The second session introduces what to consider when thinking about a career, from in-demand jobs to career paths aligned with one’s passions.

Idaho Falls middle schoolers also attend an annual career fair featuring dozens of local representatives from a variety of fields.

Keeping it to two advising sessions and a career fair is a good approach for middle schoolers, said Taylorview eighth grader Alyssa Gemar.

“It’s not like they’re always stopping us and asking what we want to do when we grow up,” she said.

Eighth grader Justin Wilkins said he’s OK with discussions about his future. Plus, benefits from Black’s sessions carry over to the classroom.

“(The Lego activity) was helpful for working in a group setting,” he said.

Black said middle school sessions also benefit her.

“It helps them know who I am, so I am a familiar face when they get to the high school,” she said.