As school districts prepare for the first day of classes, they are working to solve two conflicting problems: a rising need for mental health services and a troubling shortage of mental health professionals.

School counselors are maxed out, so districts have secured grants and support from community health partners to bring in licensed clinicians.

But, as Katie Azevedo put it, “we have the money and the system in place, but we don’t have the bodies and we need good, capable people.” Azevedo is the founder of Results Learning Center, an online institution that aims to improve social, emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes for students.

Without enough highly-trained professionals to meet student’s mental health needs, districts are getting creative. They are renewing their focus on relationship-building and preventative practices and turning to their communities for support.

“Schools cannot do it alone,” Azevedo said at an administrators’ conference last week.

Youth mental health challenges are on the rise, nationally and statewide

In surgeon general Vivek Murthy’s most recent report on youth mental health, he wrote that “recent national surveys of young people have shown alarming increases in the prevalence of certain mental health challenges.”

“It would be a tragedy if we beat back one public health crisis only to allow another to grow in its place,” Murthy wrote.

Data specific to Idaho shows the same trend of increasing mental health needs among youth.

Recently-released 2022 Kids Count data shows increasing anxiety and depression rates among Idaho children, the Idaho Capitol Sun reported this week.

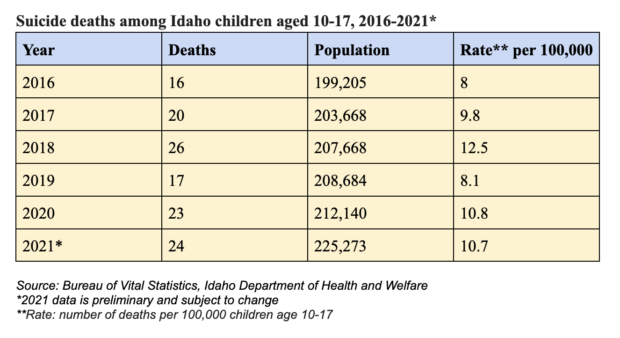

And the state’s rates of youth suicide (which is inextricably linked to mental health) are distressing. Bureau of Vital Statistics reports that those rates have increased from 8 to 10.7 between 2016 and 2021.

America’s Health Rankings pegged Idaho at 46th in the nation for teen (ages 15-19) suicide completions (2020). It calculated Idaho’s 2020 deaths per suicide at 22.2 per 100,000, compared to 11.1 nationally; the state’s 2021 rate was 20.7 compared to the national 11.2.

On top of those dire statistics, 2021 data from the National Alliance on Mental Illness shows that 52.5% of Idaho youth (ages 12-17) who have depression did not receive any care in the past year.

But local school districts are doing what they can to bridge that gap – it isn’t an easy task.

Counselors are overworked and scarce

Most school counselors are also responsible for administrative tasks, which can impact their ability to meet student demand for counseling services.

Jefferson County School District Superintendent Chad Martin expressed frustrations with that reality at the Idaho Association of School Administrators conference last week.

“How much time do counselors spend counseling versus doing schedules and testing?” Martin asked. “It’s ridiculous that we’re paying these highly-trained individuals to do all these other things.”

What’s more, school counselors’ caseloads can include hundreds of students and student demand for mental health services is increasing.

So some districts are bringing licensed clinical counselors and therapists into the schools.

This school year, the West Ada School District is partnering with community mental health providers to do just that. That way, students don’t have to miss extra class time to travel off campus to meet with counselors and parents don’t have to take time off work to transport students.

“We want to increase the ability of students to learn by addressing mental health needs,” Kylee Bendorf, the district’s counseling and student services administrator, said.

The counseling sessions will be paid for with families’ insurance. Each school will have a team to help identify which students need the counseling, and parents will be involved in that identification process.

The Twin Falls School District provides five free counseling sessions per incident (a divorce, a fight at school, a death in the family, etc.) for students and/or family members. The sessions are paid for with ESSER funds. Once that money runs out, the district will assess how and whether to continue paying for the services.

The district started offering the free sessions in January. So far, 96 individuals have used it for a total of 331 visits. The district is also working with local health providers to raise awareness about the initiative via fliers, social media posts, posters, and emails.

Margaret Wimborne, a spokesperson for the Idaho Falls School District, said they are looking at placing counseling interns in schools to support the existing counseling staff.

But as districts work to increase student access to clinical mental health providers, many have had to contend with a dearth of mental health therapists.

“It doesn’t matter what region I’m in, [the counselor shortage] is a top concern for everyone,” — Jackie Yarbrough, senior program officer for the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health

Tori Torgrimson, the behavioral health director for Family Health Services, said counseling’s inherent stresses and liabilities and the impacts of the pandemic have contributed to the shortage.

“The overall need for mental health services is a lot higher, so it’s taking a system that was already stressed and adding more need and a higher level of care that’s needed,” she said.

FHS currently works with 20 schools in six different districts (including Twin Falls, Shoshone, Buhl, Jerome, Cassia, and Kimberly) by placing clinical counselors in their schools. However, only 12 of those schools are lined up with a counselor for this school year; FHS is still trying to find staff for the remaining 8 locations.

Because there are not enough counselors, patients are experiencing longer wait times until they can be seen. By the time they do get a session, their symptoms are often more severe.

Jackie Yarbrough, the senior program officer for the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation for Health, said a lack of counselors is a common trend. The foundation’s Healthy Minds Partnership “helps establish school-located behavioral health so students can receive … services at school”. However, they’ve only been able to secure clinicians for 7 of the 10 schools and districts involved in the program.

Yarbrough said the lack of counselors is the same across the state.

“It doesn’t matter what region I’m in, this is a top concern for everyone,” she said.

Because of that shortage, the foundation has provided Idaho State University with $1.5 million to help increase the number of mental health providers in the state and improve access to healthcare in rural communities. The funds will provide up to 50 individual scholarships annually for Idaho students majoring in behavioral health programs at Idaho State.

But adding in-house clinicians isn’t the only route for schools looking to address mental health.

Schools foster strong relationships and a sense of belonging to boost mental health

Becky Meyer, superintendent for the Lake Pend Oreille School District, said it’s essential for youth to have at least one trusted adult in their lives. She wants everyone in her district – including custodians, teachers, paraprofessionals, bus drivers, and counselors – to know the importance of building those relationships.

“Every student matters,” she said. “We don’t want any student to fall through the cracks.”

Phil Schoensee, the principal at McCall’s alternative Heartland High School, has reiterated the same message with a “We Belong” campaign. The campaign involved hanging student photos around the school and was supported by a grant from the Idaho Lives Project, a suicide prevention program.

The school will also use the grant to offer a few team-building activities this school year, including bumper cars, ice skating, and skiing. Students will also receive mental health training and the school has incorporated the Sources of Strength program (as have many other districts and schools).

Sources of Strength is a national suicide prevention program “that uses peer leaders to enhance protective factors associated with reducing suicide at the school population level.”

“Having an ongoing support … is one more reason to fight off thoughts of suicide or things that could lead to that.” — Phil Schoensee, principal at McCall’s alternative Heartland High School

“It just gives us an ongoing reminder to our students and our staff of how to support one another and make sure we’re focusing on those positive things even though everyone here has challenges in their life that places them at risk,” Schoensee said. “Having an ongoing support … is one more reason to fight off thoughts of suicide or things that could lead to that.”

Keith Orchard, the mental health coordinator for Coeur d’Alene School District, said that – like most districts – they saw “increased student mental and behavioral health concerns” in the wake of the pandemic.

They’ve worked to address those needs by implementing the Sources of Strength program and training its staff as Question, Persuade, Refer suicide gatekeepers.

“Our school staff strive to build strong relationships with all students, to structure their schedule and environment to meet physical and sensory needs, and to teach students how to recognize and regulate their stress so they can be present to learn,” he wrote in an email.

But the onus to help Idaho’s youth doesn’t fall just on schools, according to one Boise State University professor.

It takes a community effort to solve youth mental health issues

Especially since the pandemic, schools have been tasked with the social, emotional, and academic needs of students and families. Megan Smith, a public health and population science associate professor at Boise State University, sees the heavy load schools are carrying and has spearheaded a project to support them.

“It’s hard for anyone to feel like on their own they can solve youth mental health; it feels like an insurmountably large problem,” Smith said. “The goal here is to coordinate efforts … and bring us all together so that the burden is light to lift.”

The project, which is funded with a $500,000 grant from the Idaho Department of Health and Welfare, aims to help communities assess youth mental health and initiate solutions tailored to their specific needs. Boise State professors and students and the St. Luke Health System’s Communities for Youth team will also be assisting.

Last spring, Smith and project members started issuing surveys and facilitating youth listening sessions in several locations throughout the state, including Twin Falls, Boise, Mountain Home, and Coeur d’Alene. More listening sessions are planned this fall, and the group will present its findings afterward.

The goal of the listening sessions is to identify a community’s youth mental health challenges and think of solutions. For example, Smith said she implemented this program in a West Virginia community where young people were experiencing high levels of loneliness. Because of that, the community’s elderly decided to start going into schools to visit students. It was awkward at first, Smith said, but then relationships started forming and youth loneliness decreased.

“We all want our kids to thrive, be happy and healthy, and go on to contribute to the world in good ways.” — Megan Smith, public health and population science associate professor at Boise State University

So far in Idaho, Smith’s group has found that young people are feeling disconnected from each other, from their parents, from their schools and communities, and from themselves. That’s partly due to time spent online.

“The pandemic … pushed young people deeper into digital worlds because they didn’t have a physical world to enter,” Smith said.

The pandemic also further polarized communities and stressed families who were already vulnerable, all of which put heavier burdens on young people.

The project also hopes to collect actionable data on mental health among Idaho’s youth. Without such information, Smith said “we can’t ever be on the preventative side, only on the outcome side. Then all we know is when young people complete suicide. At that point there’s nothing we can do.”

With so much at stake, Smith hopes the project will help communities share accountability for youth mental health outcomes and lift some of the weight off schools’ shoulders.

“We all want our kids to thrive, be happy and healthy, and go on to contribute to the world in good ways,” she said.