Millions of American children are learning the new way to do math based on Common Core State Standards: Gone are the traditional methods of carrying numbers or multiplying tables, replaced by intuitive ways of understanding basic principles like division or subtraction. Thousands of parents have spoken out, saying the new standards are bewildering and render them unable to help their kids with homework they thought they had mastered long ago.

But at Anser Charter School in Boise, new math is old hat.

Anser began serving as a pilot for what is now known as Common Core math back in the early 2000s, when Boise State University professor Jonathan Brendefur introduced Mathematical Thinking for Instruction methods to the start-up charter school. The collaboration has paid off: Anser is now considered a national leader in teaching math.

“We’ve been doing what the state is requiring teachers to do for 15 years,” Anser Organization Director Heather Dennis says. “It’s funny for me to listen in the news; you hear parents are really stressed out about trying to help their kids with math right now with this transition. But I remember that as a parent myself when my kids were here. I remember that exact same frustration: ‘How do I help them? I don’t know how to do this!’ Everyone else is going through our growing pains.”

What would a “dream” school look like?

For Anser, growing pains are an essential part of the process. The school was founded in 1999; it was the first charter school in the Boise Independent School District and the second charter school in the state.

Suzanne Gregg, Anser’s education director, is a founding member of the school. Gregg joined Boise’s Garfield Elementary Principal Darrel Burbank’s call to his fellow teachers, asking: What would a “dream” school look like?

“It wasn’t that we were unhappy where we were at,” Gregg says. “In fact, most of us were happy.”

But the idea of a from-scratch school — one that included deep parental involvement and excellent professional development for teachers, as well as consistency for students — was too much to pass up.

The founders originally envisioned a private school with plenty of scholarships for low-income children, but, as Gregg says, “that didn’t go over well.” The idea for Anser was born as states across the nation were embracing charter schools as ways to push change and innovation, and the founders decided to explore that route instead.

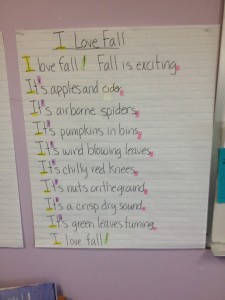

For three years the founders met regularly, devoting weekends and summer vacations to building their vision. They delved deep into the Expeditionary Learning model, which was developed by Outward Bound founder Kurt Hahn and stresses in-depth, project-based learning. Anser served as a pioneer for other charter schools around the state.

“The relationship with the chartering district was new to everybody,” Gregg says. “I think they felt like we were stepping away from public education, and nobody really understood a lot of what was happening. So the first year was a rough, rough year all the way around.”

Anser opened on Sept. 7, 1999, with 117 students. By December 1999, the school was big enough for a move to the gym at the former Bronco Elite Athletic Club (there were a lot of runny noses from leftover chalk dust, Dennis says). By 2005, it was clear the school needed more space — and to get it, Anser had to be creative.

Doing more with less

The new building in Garden City, which Anser occupied in 2011 — increasing enrollment to more than 350 — was purchased and renovated thanks to a capital campaign that soldiered on despite the crippling recession. The J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Foundation and the Laura Moore Cunningham Foundation provided funding, but parents and family and community members stepped in and opened their pocketbooks.

Ninety-seven percent of the financial pledges Anser accumulated were fulfilled, Dennis says. Anser raised $850,000. This is especially important because charter school students in Boise, according to a recent study by the University of Arkansas, receive 42.7 percent less funding than students enrolled in a Boise district school. Boise charter schools do not receive local levy dollars.

“You’re not going to find a school operating on less money per pupil,” Dennis says.

In many ways, Anser is in the same position as a rural school without access to property wealth, Dennis says. “We’re very similar in our challenges,” she says. “There is a point at which you have to give up on things that you would like to do because you can’t afford to do them. We don’t have a reading specialist. We have larger class sizes. We had to increase that. That has a really big impact in the way teachers are able to teach and what they’re able to teach. We don’t have the custodial staff we really need. We don’t have a school nurse. People wear a lot of hats, and I think any small business is that way — it’s very similar to a small business.”

The lack of funding is mitigated by Anser’s Family Council, which puts on two major fundraisers a year. “Anser is fortunate in so many ways other schools aren’t in that we do fundraise almost $130,000 a year,” Dennis says. “We have committed parents, but we also have parents who struggle financially, too, like any other school.”

Anser’s can-do spirit

Anser’s can-do spirit is critical to its success, says parent and Family Council (the school’s parent organization) member Erin McCarter. McCarter’s daughter, Ruby, is in eighth grade; her son, Indy, is in fourth.

“That’s one of the things I really love about this school,” she says. “There’s constant examination of practices and outcomes and a movement toward making it as good as it can possibly be. It doesn’t matter if there’s a change every year; I love that. I feel like too many times people are like, ‘Oh, we can’t really do an overhaul because that will be too hard and people will be upset. Here, it’s like, ‘Let’s just keep improving.’”

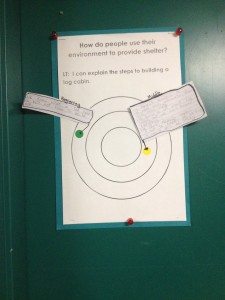

That attitude includes the children, McCarter says. They’re encouraged to create multiple drafts when writing, for example, under the assumption that their first effort won’t be their best. Instead of traditional parent-teacher conferences, students conduct their own learning assessments and present their work to their parents. And the students hold each other accountable, Ruby McCarter says.

“You can’t talk bad about somebody, and you can’t feel bad about yourself, and it’s hard to get into an uncomfortable position here because the community is so supportive,” Ruby McCarter says.

The school’s community really is special, says board member Penelope Gaffney. Gaffney has three children in the school. “It just feels like an incredibly responsive community I can be part of and continue to be actively engaged in their learning,” she says.

Gaffney’s family found Anser when they were looking for a more hands-on school for their oldest son, Brennan, who is now in seventh grade. Brennan received the extra attention and mental stimulation he needed to thrive, Gaffney says, and his development has been “phenomenal.”

“The other thing I really appreciate and didn’t expect is that my middle child is a very different person,” Gaffney says. “He has the same teachers my oldest had, but each teacher really gets to know the student and their learning styles and their best qualities, whatever those happen to be — which I love.”

Student-focused teaching style

Anser’s rigorous, student-focused teaching style has become an inspiration for other schools around the state and the nation. Anser is an Expeditionary Learning mentor school. It’s also a studio district for Idaho Leads, a project of Boise State University’s Center for School Improvement and Policy Studies. The school recently hosted visits from schools in Melba, Gooding, Star, and Idaho Falls, and held a three-day math institute in October with food provided by parents.

Helping other teachers is one of the core philosophies at Anser, Gregg says. “One of the tenets of the school is to give back to the profession,” she says. “We’ve got some really high quality and highly effective teaching staff, and I think that’s based on our rigorous interviewing process we have teachers go through.”

Teachers must thrive through an intense screening protocol, which includes a portfolio and interviews with parents, board members — and students. But the responsibility for hiring rests with the teachers who will be part of the new instructor’s team: At Anser, grades are joined in pairs, so teachers work together extensively. New teachers “very rarely” have experience in expeditionary learning, Gregg says, so instructors participate in a lot of training.

But all of that extra work shows through in the students, Dennis says. She hopes Anser will always be focused on what is right for each child.

“We’re about students reaching their own, personal bests and their potential,” she says. “And that looks different for everyone.”

Anser is one of Idaho’s highest achieving schools. See the data at IdahoEdTrends.org. This is the first in a six-part series featuring Idaho charter schools. This series is being provided by the Idaho New School Trust.