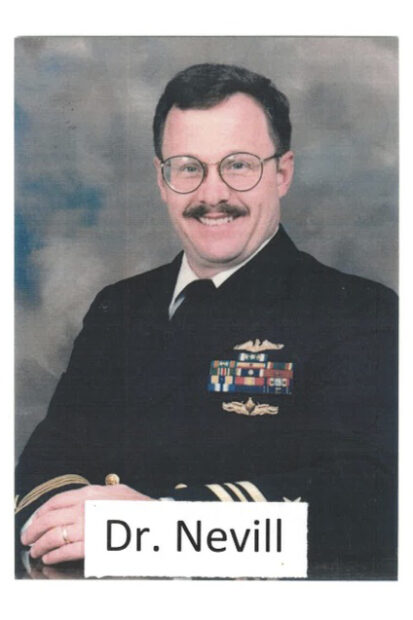

Months before Harold Nevill’s retirement date, he was planning his successor’s next steps.

Nevill wants the next leader of the Canyon-Owyhee School Service Agency (COSSA) to succeed. So he penned a six-page “turnover” letter that details his troubles and triumphs at the alternative and special education career-technical school that draws students from five rural school districts.

The former submarine operative covets the practice that he learned from his two decades in the Navy.

Nevill, a meticulous veteran with a second-career passion for preparing students for the workforce, will retire this month after leading the Treasure Valley community school for more than a decade. After a lifetime of serving others by devising policies, serving on foundation boards and on months-long submarine trips, he is looking forward to more time to think and learn.

“I still believe in hard work. And I try to put in a full day of work, whether it’s here or home, everyday that I’m above ground,” said Nevill, whose last day is Wednesday.

“He’s a servant leader,” said Clay Long, Idaho’s Administrator of Career Technical Education. His leadership style is “never for his gain.”

Farmer to sailor to educator

Nevill was born and raised in Nampa to his farming parents. While he was in elementary school, Nevill’s parents moved to Payette County. He graduated from Fruitland High School in 1974 and joined the Navy, where he served on four submarines over 21 years that took him to Guam, Minnesota and Washington.

While in the Navy, Nevill graduated from Regents College in Albany, New York, with a bachelor of science in 1987, and he earned a Master of Management and Administration from Metropolitan State University in Minnesota in 1993.

He retired as a Navy lieutenant commander then moved back to the Treasure Valley with his wife and two kids. He spent a short time working for a Department of Defense contractor before turning his attention to education.

“I do believe very strongly that in America, you can still make something of yourself by getting a good education and working hard,” Nevill said.

He taught physics, science, math and electronics at Vallivue High School in Caldwell from 1997 to 2002, then becoming a career-technical electronics instructor at the Dennis Career-Technical Education Center in Boise. He also served as manager for trade and industry programs for Idaho CTE and as CTE coordinator for West Ada School District before joining COSSA as a business teacher and principal. In 2009, he earned his Doctorate in Education and an educational specialist certificate in educational leadership from University of Idaho, which led to a promotion to CEO and superintendent in 2010.

Nevill’s military background influenced his leadership style. He delegates and trusts his employees, and he adheres to the principle of hiring good people, and letting them do their thing.

He has high expectations for teachers because “the stakes are too high to slack,” he said. If students in COSSA’s alternative program fail, this may be their last shot at a high school diploma.

“When we lose students out of the alternative school, we really lose,” Nevill said.

Putting student needs first

COSSA pools together services for the students from five rural districts, programs they wouldn’t be able to offer without the partnership. Nevill also sees COSSA as an efficient use of taxpayer dollars. With so many kids under one roof, for instance, they can share classroom resources and teachers.

COSSA offers far more than classes. All students are eligible to receive free and reduced-price meals and new clothes from a community bin. Teachers are required to take trauma-informed instruction training, and Nevill asks them to deliver holiday baskets to students’ homes. Teachers overwhelmingly agreed.

“I think we started graduating a higher quality graduate,” Nevill said.

Nevill not only devotes his time to the students and staff at COSSA, but he also gives financially. He paid for the turkeys placed in holiday food baskets for staff and students, and he paid for all staff to have embroidered black “COSSA” button-up shirts. He also cut his pay in half — from $87,000 a year down to $42,500 — for two years so he could hire another administrator.

“A normal person with a normal educational career wouldn’t be able to do that,” Nevill said, noting his security from military retirement pay.

“He could have retired a long time ago,” said Wilder Superintendent Jeff Dillion. “His passion for supporting students kept him in the job.”

When conditions called for it, Nevill leaned into conflict.

Most school districts that feed into COSSA converted to four-day school weeks. But Nevill didn’t want it. One less day of school meant one more day that his students were without subsidized food, supervision and schooling.

He spoke out in favor of the five-day school week, but lost his bid when COSSA’s board, comprised of trustees and administrators in the five feeder districts, voted to drop one school day a week.

That disagreement, in part, has Nevill calling for COSSA officials to reconfigure the board. Since the board’s current structure has sitting members affiliated with leadership in their home districts, Nevill thinks it sets up board members to vote for what’s in their home districts’ best interest.

The conflict of interest is inherent with the current system, Nevill said, but he couldn’t solve the issue in his time. He mentioned wanting to revise the board’s structure in his resignation letter, which he turned in to COSSA’s board in April.

“When the ‘right thing’ for their home district is in direct conflict with the ‘right thing’ for COSSA, especially in financial matters, COSSA seems to take second place,” Nevill wrote in the letter.

A life-long learner

Nevill, a self-described introvert, had no problem driving a tractor for eight hours without any human contact. His thoughts could keep him entertained.

And the isolation on submarines, deep under sea level without the means to communicate with loved ones, proved fruitful. He’d keep busy by reading books. Over time, he became certified to perform various jobs on submarines.

Those habits remained years after his deployments.

Nevill doesn’t own a television because he thinks watching TV is a waste of time.

When not working, he’s reading. In retirement, he’ll take college courses. He wants to learn Spanish so he can communicate better with his Nampa neighbors.